How Russia made BETTER champagne than the French

In the early 19th century, Russian nobility was keen on everything French. Not only French novels and hats were brought from Paris to snowy Russia, but also some delicacies. Russian noblemen developed a special liking for French sparkling wines originated in the province of Champagne. For instance, ‘‘Veuve Clicquot’ and ‘Moët’ champagnes (the most well-known sparkling wines by the respective same-name trade houses) were drunk by the titular hero of Alexander Pushkin’s ‘Eugene Onegin’. Russians liked those sparkling wines so much that it became part of their everyday life as a symbol of luxury, joy and good taste. It gradually grew to be known simply as “champagne”. It had only one drawback: it was too expensive.

Advertisement for 'Veuve Clicquot' champagne.

Advertisement for 'Veuve Clicquot' champagne.

Champagne from Don Cossacks

Sparkling wines were not completely new to Russia: starting from the second half of the 18th century, the co-called ‘Tsimlyanskoye’ wine was manufactured in the region of the Don River. The ruby-coloured fizzy drink was well-known and much loved by the public. In terms of its characteristics, ‘Tsimlyanskoye’ was certainly behind champagnes, but was more affordable and quite popular. For example, in Pushkin’s afore-mentioned novel, ‘Tsimlyanskoye’ is served during dinner at the Larins’, who are not so well-off rural landowners.

‘Tsimlyanskoye’ wine label.

‘Tsimlyanskoye’ wine label.

To produce wine, two sorts of red grapes were harvested, after which they were sun-dried under a shelter until the first cold spells, ground and left to ferment. The wine was bottled half-fermented.

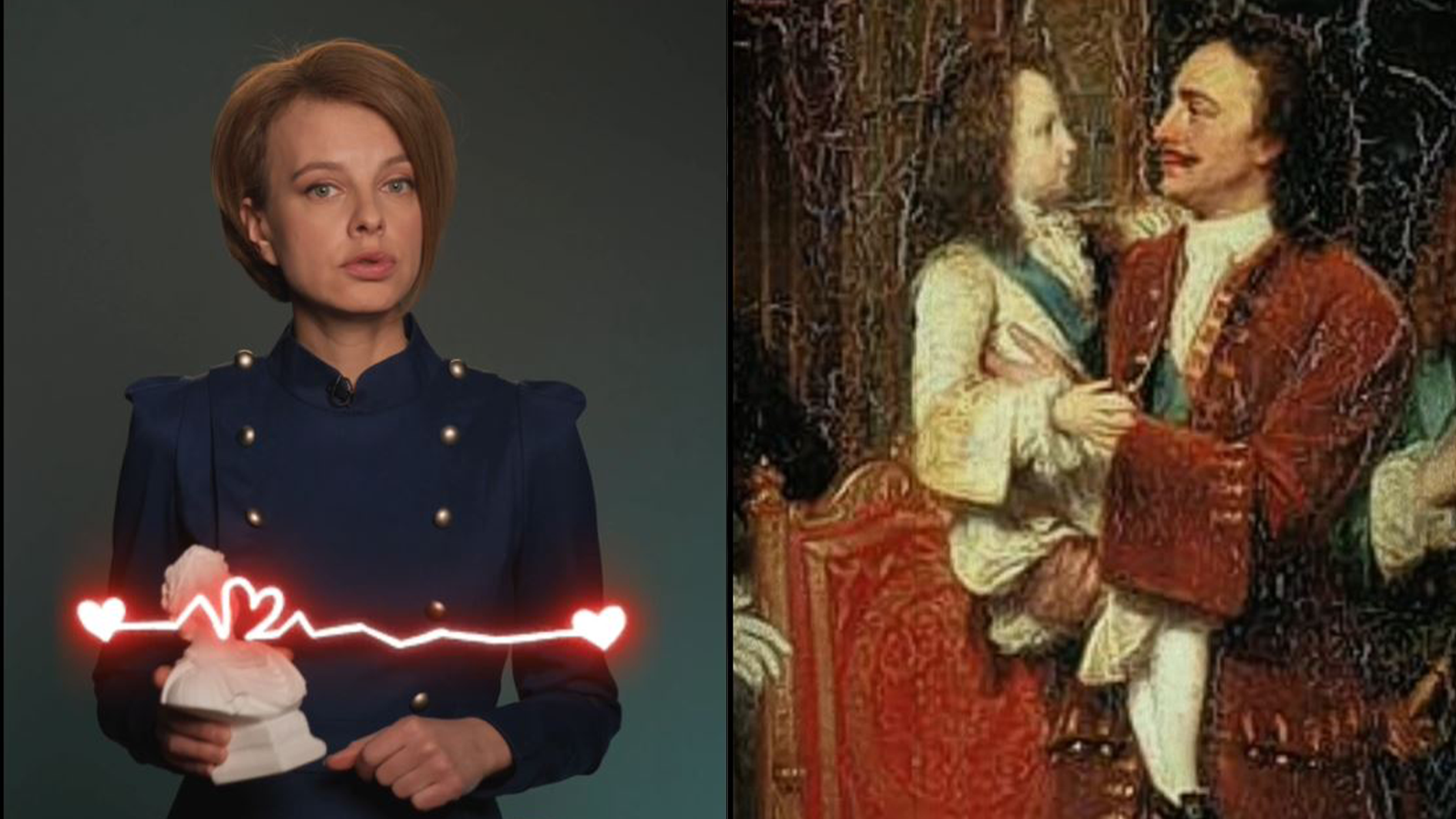

Cossack selling ‘Tsimlyanskoye’, 1875-1876.

Cossack selling ‘Tsimlyanskoye’, 1875-1876.

Multiple attempts were made in Russia to produce local sparkling wines that would be on a par with champagnes, but none were successful. The first winery was opened by Peter Simon Pallas in Crimea in the early 19th century, but it was soon closed down for fraud. The new owner of the winery decided to simply put French labels on the bottles, but it didn’t make the wine any better. Separately, Prince Vorontsov made attempts to develop the production of local champagne, but his vineyards failed to survive the Crimean War. Meanwhile, privileged circles had to order champagne from France, until Prince Lev Golitsyn took center stage.

Prince Golitsyn’s Crimean champagne

Prince Lev Golitsyn was born into a noble family and received an excellent education. While traveling across Europe, he familiarized himself with French winemaking and discovered he had a talent for winemaking. For instance, he was said to be able to, unmistakably, tell one grape sort from another by the shape of their leaves and smell. He soon felt the urge to create a Russian wine equal to French champagne. In 1878, he bought an estate called Novy Svet in Crimea, where he planted around 600 grape sorts. Golitsyn knew what sorts were used by French winemakers to make the drink, but they didn’t suit the Russian climate and soil. One and the same sort of grapes grown on different soils could yield different fruit in terms of its flavor and chemical composition. Thus, the prince personally picked only those sorts among all the diversity that were best-suited for making a high-quality drink in Crimean conditions.

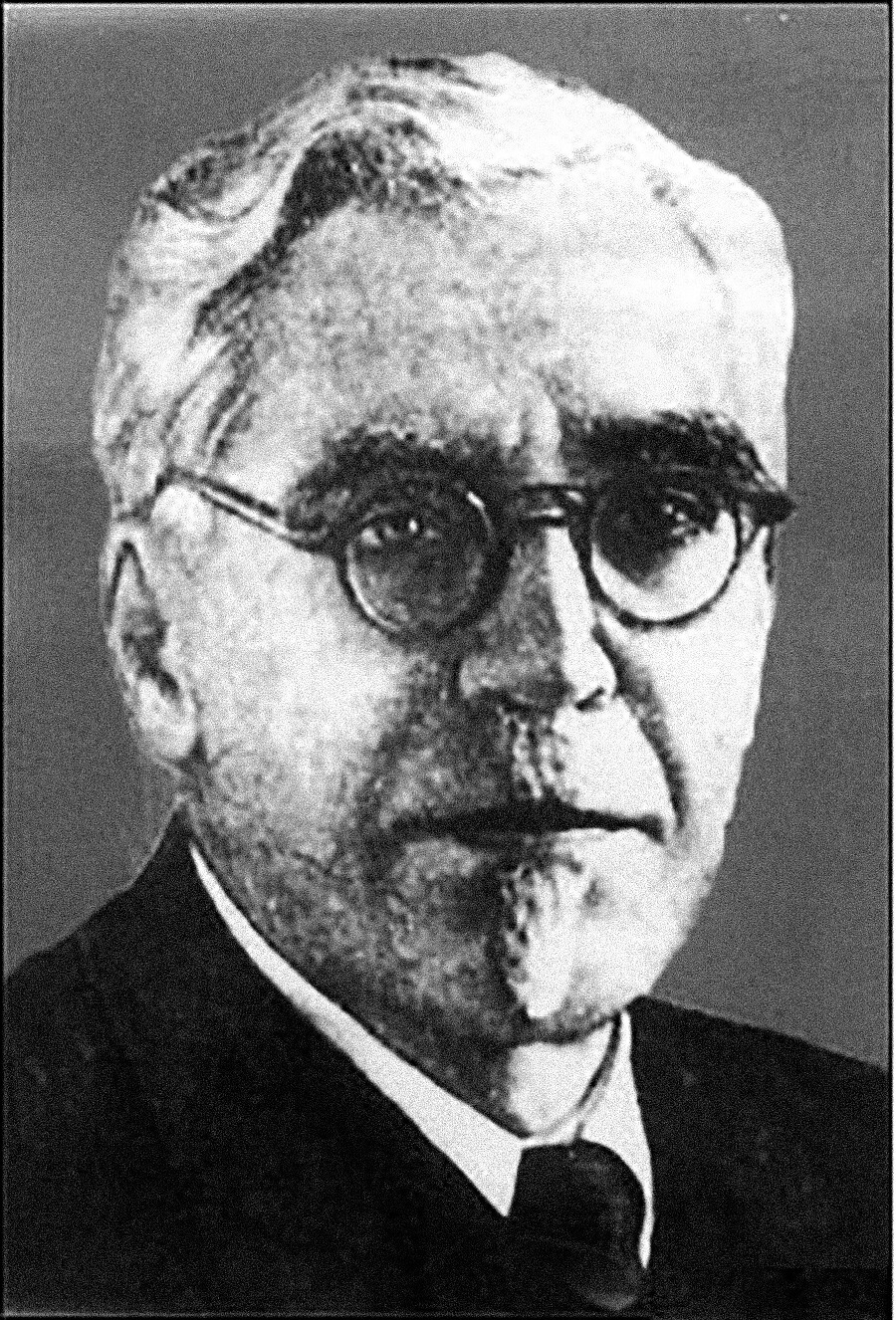

Prince Lev Sergeyevich Golitsyn.

Prince Lev Sergeyevich Golitsyn.

Golitsyn’s first champagne was ready by the early 1880s, turning out to be so good that, in just 10 years, the prince earned himself an excellent reputation at the royal court. In 1891, Alexander III appointed him to be the senior winemaker of the emperor’s estates in Crimea and the Caucasus. In 1900, at the World Exhibition in Paris, Golitsyn’s wine was awarded the Grand Prix, having beaten out all the French champagnes.

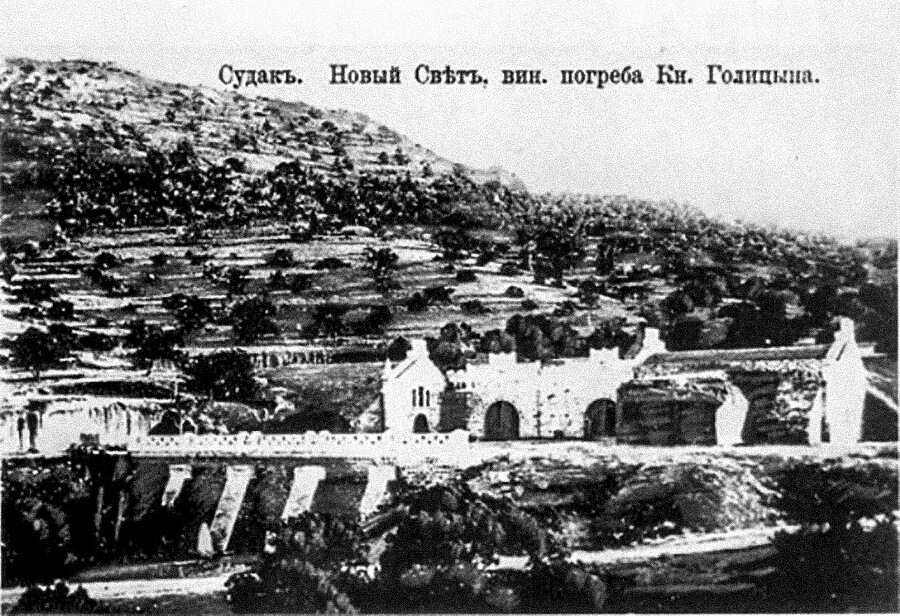

'Novy Svet' winery.

'Novy Svet' winery.

Golitsyn was an outstanding winemaker, a very creative and enthusiastic person, yet a bad entrepreneur. Despite great success his champagne achieved, in 1905, he went bankrupt. Vladimir Gilyarovsky, a famous Russian journalist and writer at that time, later depicted Golitsyn as follows: “He was splashing out his money left and right, never refusing anyone anything, especially students. He owned a wine store on Tverskaya Street in Moscow that sold wines from his splendid Novy Svet vineyards, with his pure natural wines costing only 25 kopecks a bottle, which was incredibly cheap.” “I want any worker, craftsman or low-rank servant to drink good wine!” Golitsyn would say.

Follower of a great chemist, revolutionary and winemaker

Fortunately enough, as some time passed, Golitsyn’s venture was uptaken by another promising figure named Anton Frolov-Bagreev. Having graduated from the St. Petersburg University with honors, he was recommended for a foreign exchange trip by prominent Russian chemist Dmitry Mendeleev (who famously drew up the iconic table of chemical elements) and went to Europe to continue his studies. In France and Portugal, he studied all the peculiarities of winemaking and, having returned to Russia in 1905, he became employed as a chemist at the winery in Abrau-Durso. In that same year, a wave of protests shattered Russia, with the first revolution taking place. The protesters demanded more civil rights, the improvement of their working conditions and limiting the emperor’s power. Frolov took part in demonstrations by Abrau-Durso winery workers and even signed a petition against the czarist rule, which he was dismissed for and sent to Siberia.

Anton Frolov-Bagreev.

Anton Frolov-Bagreev.

Frolov’s exile didn’t last long: starting from 1906, he was already working as a chemist-winemaker in Crimea, being showered with mercy and ranks starting from 1911. In 1919, already under the new Bolshevik rule, Frolov led champagne production in Abrau-Durso.

After the revolution, no data about the previous technology of champagne-making was preserved at the winery, so Frolov had to draw it up anew. The first samples were ready only by 1923. ‘Champagnization’ (in line with the classic technology) took too long, making champagne a costly drink that few could afford. It had to do with the period of fermentation; according to the traditional scheme, wines are bottled with added sugar and yeast before being corked and left aside for 9-12 months. Throughout this time, yeast would release carbon dioxide, making the drink fizzy. Such a lengthy fermentation decreases the total amount of supply, which means prices will go up.

Frolov set about the creation of a technology of speedy “champagnization”, finally working it out by the mid-1930s. From that moment, champagne was produced not in bottles, but in special reservoirs, fermenting for approximately a month. This technology was subsequently used in producing the famed ‘Soviet Champagne’.

The latter name sparked a real scandal at the time: when ‘Soviet Champagne’ was attempted to be exported to France, local champagne makers got frustrated by the use of the word ‘champagne’.

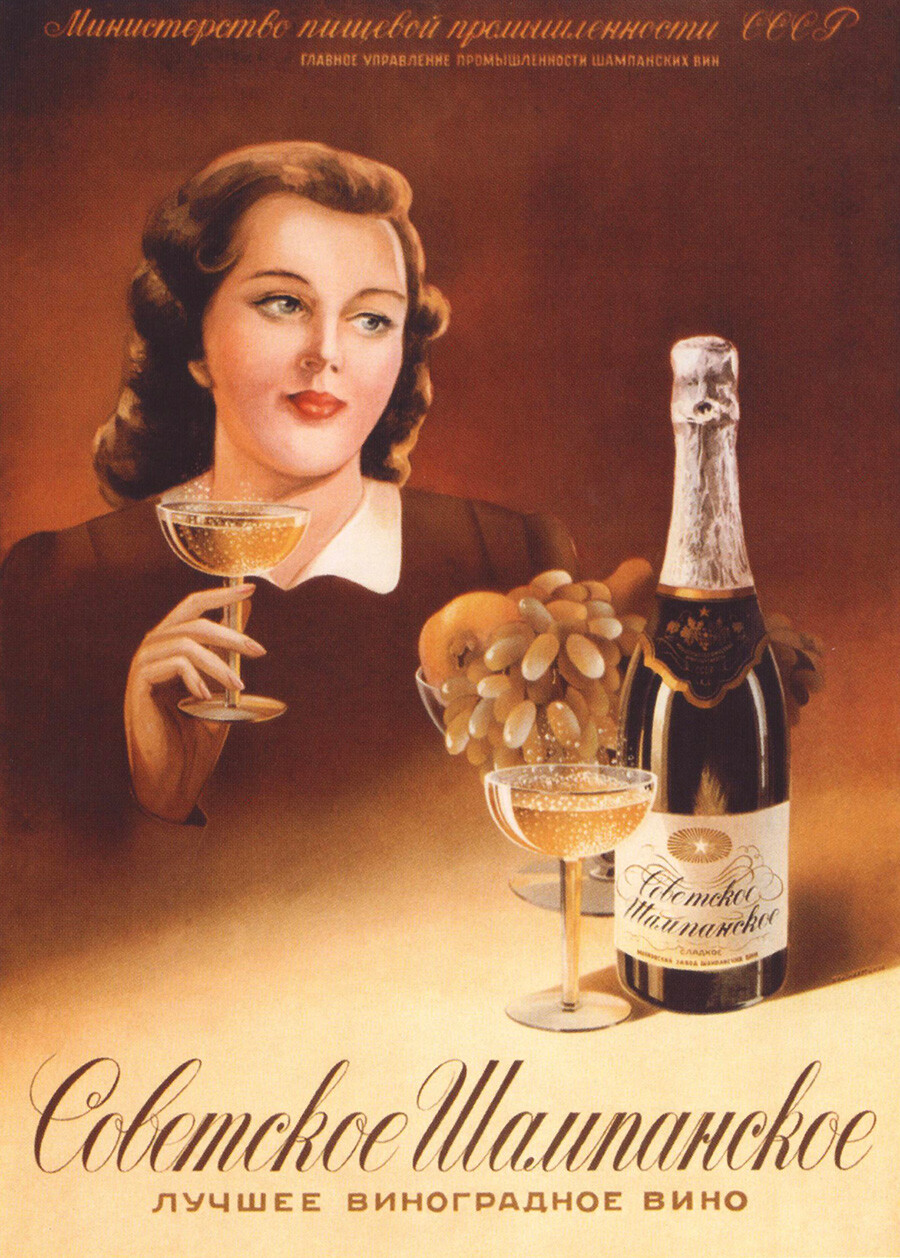

Advertisement for 'Soviet champagne'.

Advertisement for 'Soviet champagne'.

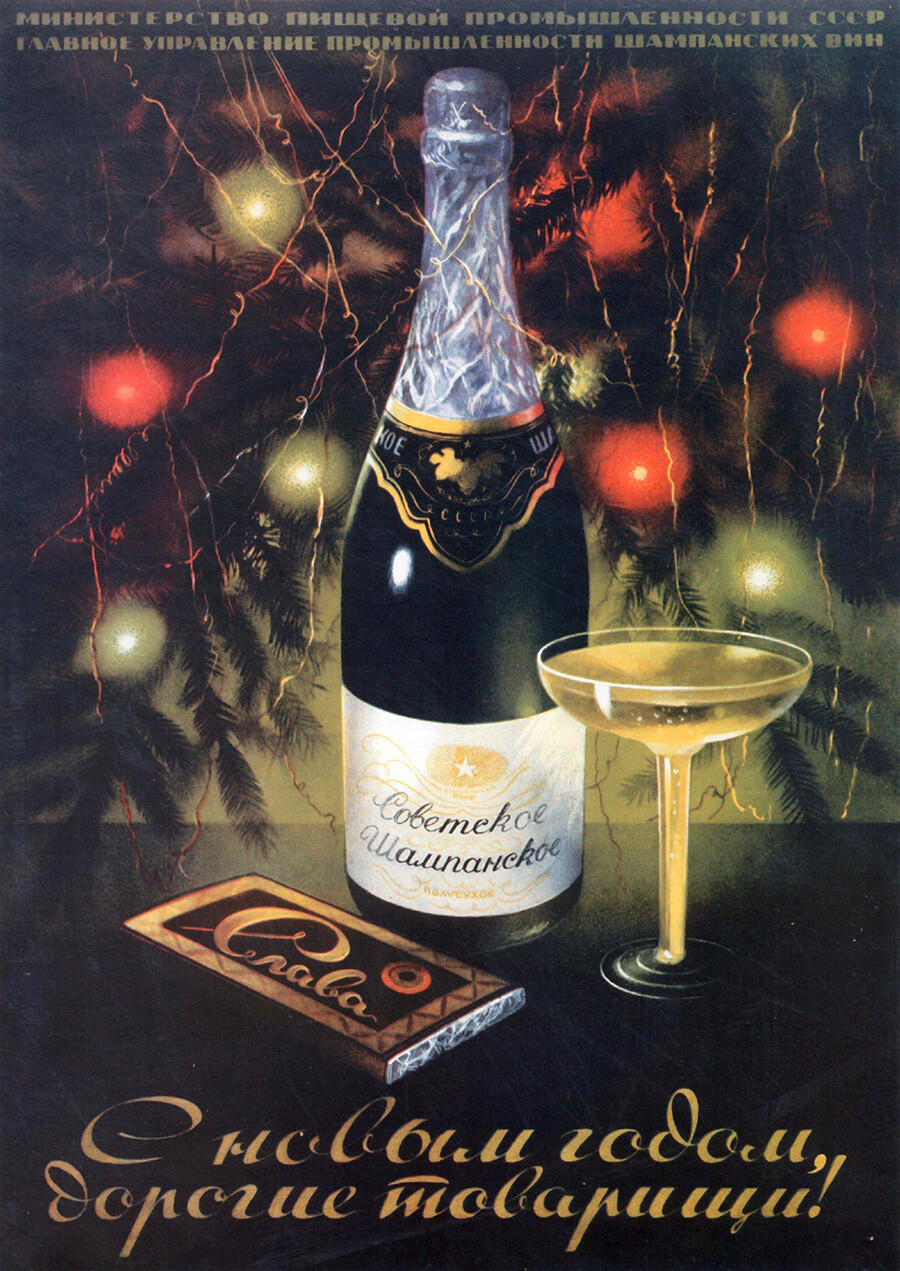

Advertisement for 'Soviet champagne'.

Advertisement for 'Soviet champagne'.

Discussions on whether Russian wines could be called “champagnes” do not abate even now. One thing is certain: Frolov-Bagreev gifted his compatriots and the world around some really high-quality and affordable wine, the production standards of which are currently employed abroad, including in France.