What kind of canned goods were produced in the imperial era and who got rich off it?

In 1900, explorers led by Baron Eduard von Toll departed from St. Petersburg on a mission to find the mysterious and elusive Sannikov Land. Their polar expedition to find the “ghost island” in the Arctic Ocean was not successful, but it marked the beginning of an experiment with canned food.

For several months the scientists were stuck in an ice trap near the Taymyr Peninsula, but still they continued their research on land and in ship laboratories. To have some food on the peninsula in case the researchers couldn’t return to the ship, von Toll ordered tin crates with food to be buried at a depth of slightly more than one meter. The crates contained rusks, oats, chocolate, tea, sugar and 48 cans of shchi with meat and porridge that had been made that year in 1900. These were produced by the first Russian cannery owned by Francois Azibert that supplied food to the imperial army.

A tin of soup with meat and porridge produced in 1900 by the first Russian cannery. It was found by expedition in 1973.

A tin of soup with meat and porridge produced in 1900 by the first Russian cannery. It was found by expedition in 1973.

The explorers, however, ended up not needing this food cache, but as per von Toll’s diaries, in 1973 another expedition managed to find the hidden food. Surprisingly, the canned food was still edible and even quite appetizing. It was tasted again in 2004 – century-old “shchi with meat and porridge” was still edible and it passed lab tests checking for quality.

How French canned food first came to Russia

Russia acquired a taste for canned food later than Europe or the U.S. The trailblazers in this field were the French. At the end of the 18th century Napoleon Bonaparte was concerned with supplying food to his soldiers during lengthy military campaigns, and so he announced a cash prize for an unorthodox solution. In 1810, this prize went to Nicolas Appert, along with the title “Benefactor of mankind”, for his invention of “appertization”. This was a method of sealing a product in a glass jar, with long boiling afterwards.

Nicolas Appert invented preserved food in glass bottles.

Nicolas Appert invented preserved food in glass bottles.

Appert invented preserved food in glass bottles, while Englishman Peter Durand, also in 1810, patented a similar method of preservation in metal cans. From 1812 onward, the production of canned food for the British military began. The technology soon began to be used by the U.S. and Germany. In the 1820s, the assortment of canned food in the U.S. was significantly expanded. No longer was it just meat, vegetables and soups. Canned lobsters, tuna, fruit and other food appeared.

One could suspect that Russia might have learned about French conserved food during the War of 1812. According to some researchers, that did happen, but that first contact ended abruptly.

Russian soldiers found preserved food on captured French soldiers but they were afraid to try it, fearing it might contain “frog meat.” Field Marshal of the Russian army Mikhail Kutuzov proved himself to be the bravest in this matter. He fearlessly tried the mysterious foreign item from a bottle and declared it safe – no frogs, just regular lamb. But just to be on the safe side, he prohibited his soldiers from eating it.

Canned food for the rich

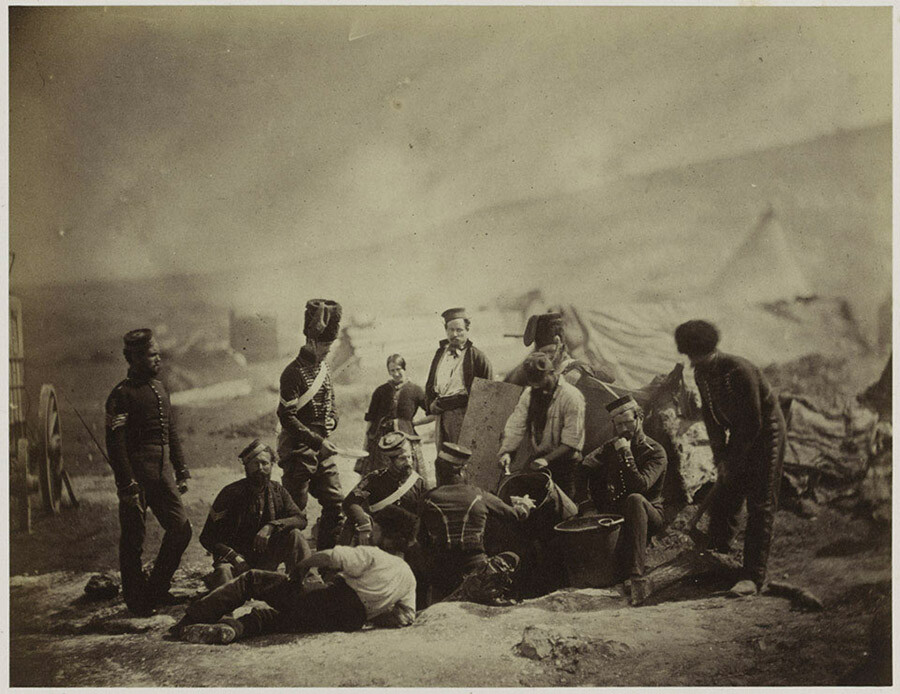

Cooking House of the 8th (The King's Royal Irish) Light Dragoons (Hussars), Crimea, 1855.

Cooking House of the 8th (The King's Royal Irish) Light Dragoons (Hussars), Crimea, 1855.

In the 1830s, canned food began to be imported into Russia as something exotic and expensive. In his play The Government Inspector (1835) Nikolai Gogol mentioned canned food in Russian literature for the first time.

His main character, the minor official Khlestakov, had been bragging about his luxurious life in St. Petersburg, “The soup comes in a tureen straight from Paris by steamer. When the lid is raised, the aroma of the steam is like nothing else in the world.”

However, we can’t say that the idea of conserving food didn’t interest Russian scientists at all. Back in 1763, while preparing an expedition to explore a Northern sea route from Russia to China and India, the famous scientist Mikhail Lomonosov made a concentrate from a dried soup with spices. It successfully survived the journey to the shores of Kamchatka, but the general public never learned anything about it.

The idea of soup concentrated in pouches was also researched by Vasily Karazin, a scientist and the founder of Kharkiv University. In 1815, he presented his idea to Count Alexey Arakcheyev (a military minister and a confidant of Emperor Alexander I) but couldn’t find any support.

Canned food remained a matter of scientific research and noblemen’s indulgence right until the Crimean War of 1853-1856. During that conflict British and French soldiers ate canned food, while Russian soldiers suffered from a lack of proper foodstuffs. Then, Russia started looking at canned food as a long-standing food supply for the army, and so, Emperor Alexander II ordered the purchase of a trial batch of canned food from overseas.

Russia’s first cannery

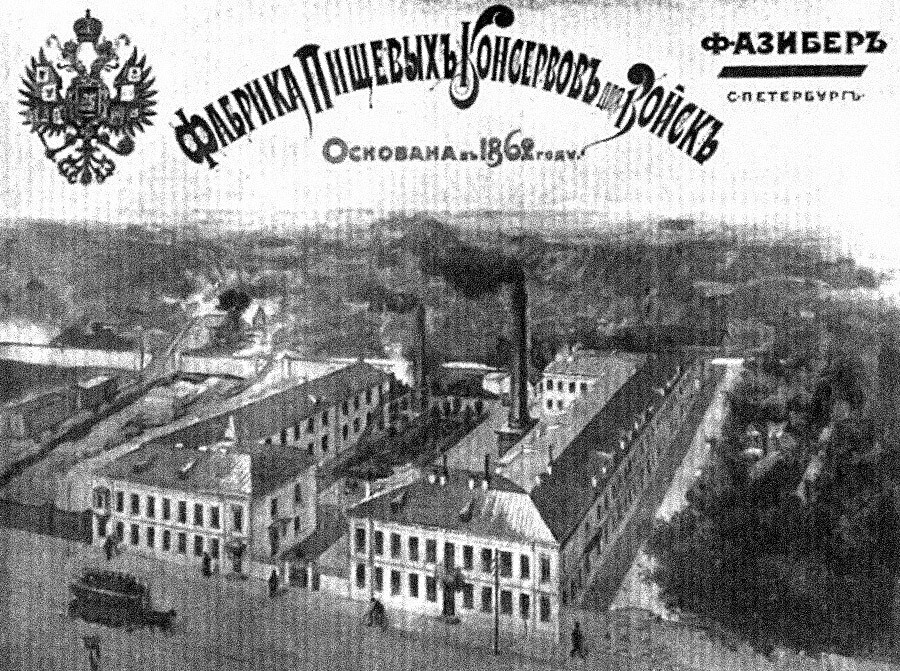

In 1870, the St. Petersburg Military Medical Academy started studying the feasibility of contracting out to Russian canned food producers in order to find ways to feed soldiers in the field. The opportunity to make samples of canned food for the military was offered to Frenchman Francois Azibert, whose factory had been operating in St. Petersburg since 1862. At that time, his cans with vegetables and mushrooms had been sold on local markets and to wholesale traders. Samples prepared for the military successfully passed tests at local hospitals, and after some time Azibert received a long-term military contract.

In 1887, five types of canned food for the army were developed and put into production: fried beef (or lamb), ragout, shchi with porridge, peas with meat and canned vegetables.

Canned food kings

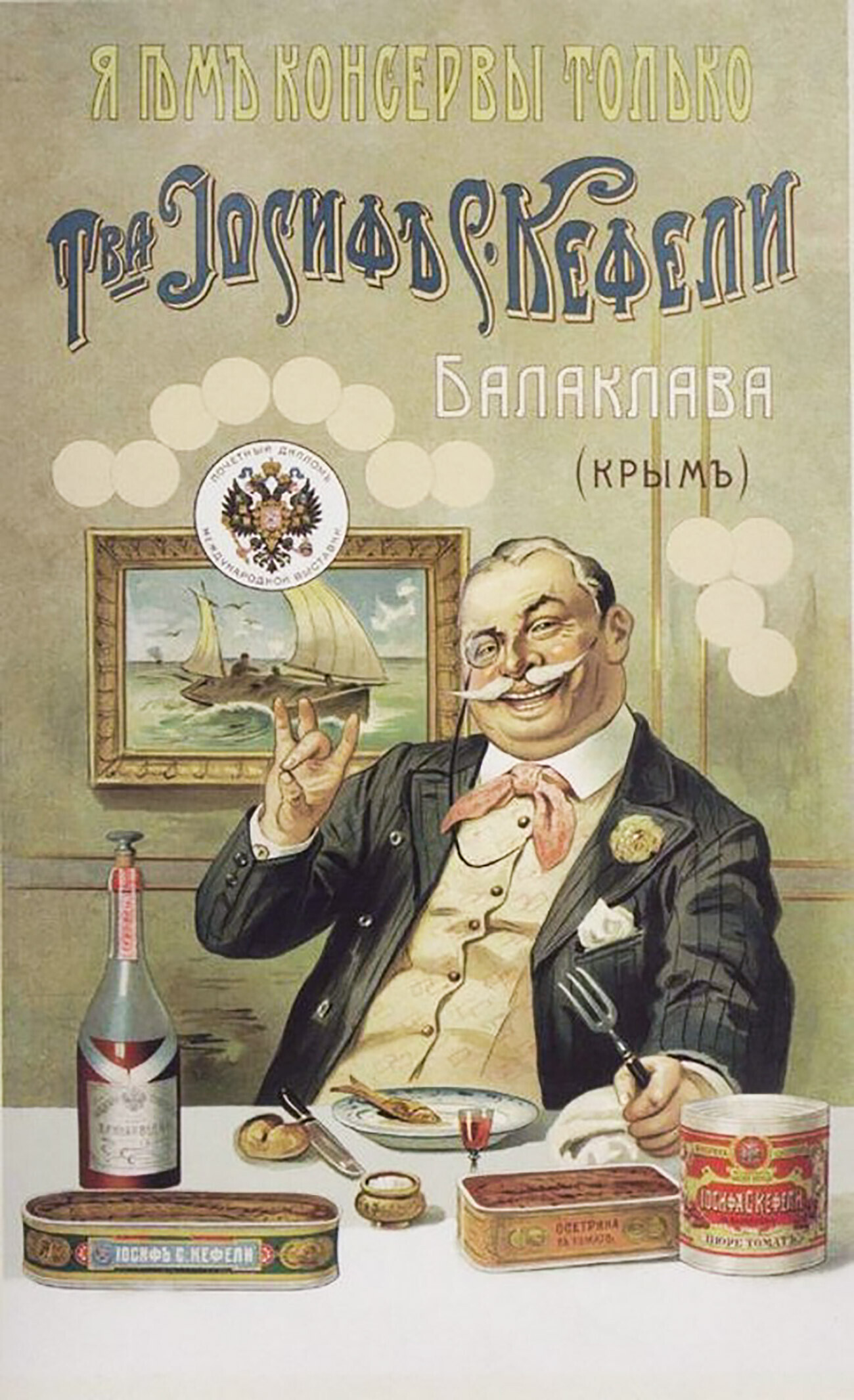

A poster advertising canned food from Joseph Kefeli's cannery.

A poster advertising canned food from Joseph Kefeli's cannery.

Another enterprising Frenchman with the surname Mallone came up with the idea to gather peeled peas from the locals in the Yaroslavl Region and can them. Before that the locals were only drying the peas. The pea canning factory started operation in 1875. Later, cucumbers and other local vegetables were also conserved. These items were sold in Russia and were also exported.

Another cannery was opened by Joseph Kefeli in 1892 in Balaklava on the south-west shore of Crimea. Local fishermen were fishing for mullets, mackerel, beluga and other fish. Right at the factory, the Black Sea fish was turned into canned delicacies that were then successfully sold across the empire.

The meat canning business of a German by the name of Birman living in the city of Kozlov was also successful, but his story ended tragically. Even before the 1917 Revolution, he built a slaughterhouse (which processed 300-400 heads of cattle per day) and established the production of canned meat. The workers couldn’t handle the harsh working conditions at the enterprise; in 1916 they went on strike and set the factory on fire. Birman fled Russia, leaving a foreman at the factory. But in 1919 the factory was entirely destroyed and looted by soldiers and locals during the Civil War.

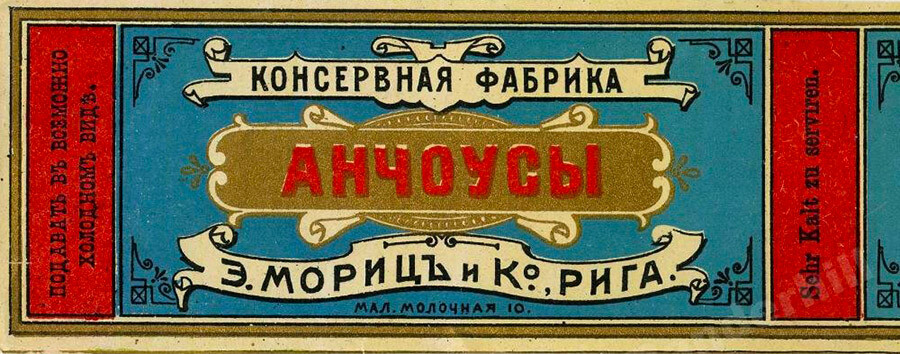

Label of canned food produced in Riga.

Label of canned food produced in Riga.

In order to comprehend the vast scale of production, it’s enough to point to one fact: in 1904-1905 canneries in St. Petersburg, Odessa, Riga and Mitau (these last three cities were part of the Russian Empire) that were working for the Defense Ministry produced 250,000 tins a day and up to 75 million per year. According to official data, at the beginning of World War I the country’s largest canneries produced 70,000-100,000 portions daily (“War economy during World War I”, G.I. Shigalin).

The most unusual can could self-heat

In 1897, engineer and inventor Evgeny Fyodorov invented a can that self-heated. This can had a double bottom, and held water and quicklime. Both chemically reacted when the bottom was twisted, which led to the can being heated. The production of such innovative cans was set up in 1915, and they were sent to the front to feed Russian soldiers during World War I. Without any smoke that might expose their position, the soldiers were able to enjoy a warm dish. However, the novelty wore off, and its production in Russia eventually came to an end. Similar cans, however, were later used by German troops during World War II. In Japan, this technology is still used in canned food production to this day.

READ MORE: How French cuisine conquered Russia (unlike the French army)