How the USSR fought Darwinism & genetics

Soviet authorities supported the idea of class struggle (Marxism), but rejected the intraspecific struggle for survival (Darwinism), as well as the entirety of classical genetics.

Peasant scientist Trofim Lysenko

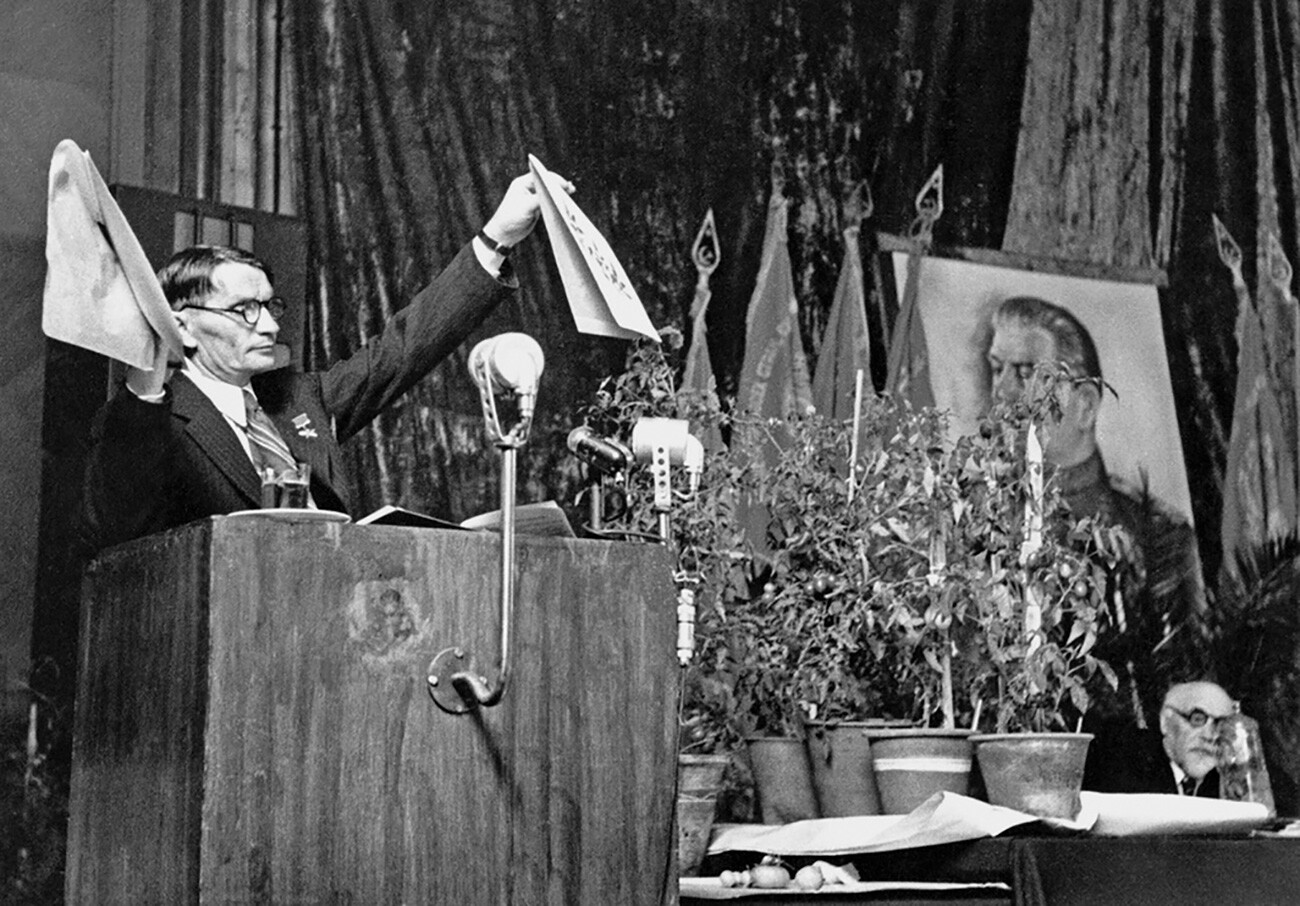

Trofim Lysenko speaking at the Kremlin in 1935. At the back (left to right) are Stanislav Kosior, Anastas Mikoyan, Andrei Andreev and Joseph Stalin

Trofim Lysenko speaking at the Kremlin in 1935. At the back (left to right) are Stanislav Kosior, Anastas Mikoyan, Andrei Andreev and Joseph Stalin

Agronomist Trofim Lysenko became an ideologist of the Soviet way of biology in general, as well as of the theory of evolution, in particular. In 1928, he developed a new agricultural technology – vernalization: it was proposed to cool cereal crop seeds for them to produce more yield. The idea was supported by many scientists; the Soviet press began praising Lysenko, enthusiastically drawing attention to his peasant background – as opposed to highly educated scientists, who had studied and worked already back in Tsarist Russia and had traveled overseas, soaking in bourgeois ideas.

Lysenko became an influential agronomist and received a lot of important positions – in 1938, he became the president of the Lenin All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences. He continued to propose new, sometimes almost unbelievable, agrotechnical and selectionist ideas.

From 1936, Lysenko headed the Breeding and Genetic Institute in Odessa. Pictured in 1938 with the Institute's staff

From 1936, Lysenko headed the Breeding and Genetic Institute in Odessa. Pictured in 1938 with the Institute's staff

He gained a lot of followers; people began to often call his doctrine and this area of biology ‘Michurinist agrobiology’. Famous scientist and practitioner of selection Ivan Michurin had nothing to do with it, it’s just that Lysenko considered himself to be his follower.

But what instead of Darwinism?

The main goal of agrobiology, as outlined by Lysenko, was to increase crop yield; he planned to do it with new approaches, without leaning on “hostile capitalist doctrines”.

The main object of Lysenko’s attacks was Darwinism. He denounced the evolutionary concept of Darwin with its theory of organisms’ inequality as pseudo-scientific and racist overall. He began to call classical genetics a fascist science.

Lighting of the experimental fields of the Trofim Lysenko Institute near Kiev

Lighting of the experimental fields of the Trofim Lysenko Institute near Kiev

Lysenko supposed that the development of a living organism depends not so much on heredity and genes, but on its external environment. He also believed in inheriting acquired skills.

And – mainly – he rejected intraspecific competition. For example, he advocated new square cluster ways to plant ‘kok-saghyz’ (a rubber plant). According to him, the yield was supposed to grow exponentially. That being said, Americans advocated against such a method, since some plants, if planted too close to one another, didn’t grow at all or grew weakened. Lysenko responded that the principle of intraspecific competition was invented by bourgeois science: “There is only interspecific competition: a wolf eats a hare, but a hare doesn’t eat another hare – it eats grass. One type of wheat also doesn’t bother another.”

Kok-sagyz is a rubber-bearing plant in the genus Dandelion

Kok-sagyz is a rubber-bearing plant in the genus Dandelion

Lysenko also claimed that species can turn into one another under the influence of their external environment. “To reject that wheat in specific conditions spawns separate seeds of rye that later grow and displace wheat is to turn away from life and from practice.”

The struggle against scientists & bourgeois doctrines

Lysenko speaks out against genetics at the session of the Academy of Agricultural Sciences, 1948

Lysenko speaks out against genetics at the session of the Academy of Agricultural Sciences, 1948

For Lysenko, Scientific theories were inextricably linked to ideology and social order. He stated that the bourgeois science of biology clings so much to its precious “theory” of intraspecific competition, because it needed to justify why capitalist society has so many people living in poverty.

He also said: “We, the Soviet people, know well that the oppression of the working class <…> doesn’t have anything to do with any laws of biology.”

He proposed to fight “ideologically alien” doctrines brought from the hostile abroad. With the Party’s approval, Lysenko claimed classical genetics was a pseudoscience. And a whole campaign against ideologically “undesirable” scientists began.

Trofim Lysenko

Trofim Lysenko

Those who engaged in genetics (and not Lysenko’s agrobiology) were fired from their positions. Scientists who criticized Lysenko’s ideas were also prosecuted. The entire research process was brought under the control of ideology. Later, the same fate befell other branches of biology – virology, cytology and other sciences.

Prominent geneticist Nikolai Vavilov, for instance, was arrested in 1940 – formally for “sabotage” – and he later died in prison (After the death of Stalin, he was posthumously rehabilitated and praised as a great scientist, so now many Russian cities have streets named in his honor).

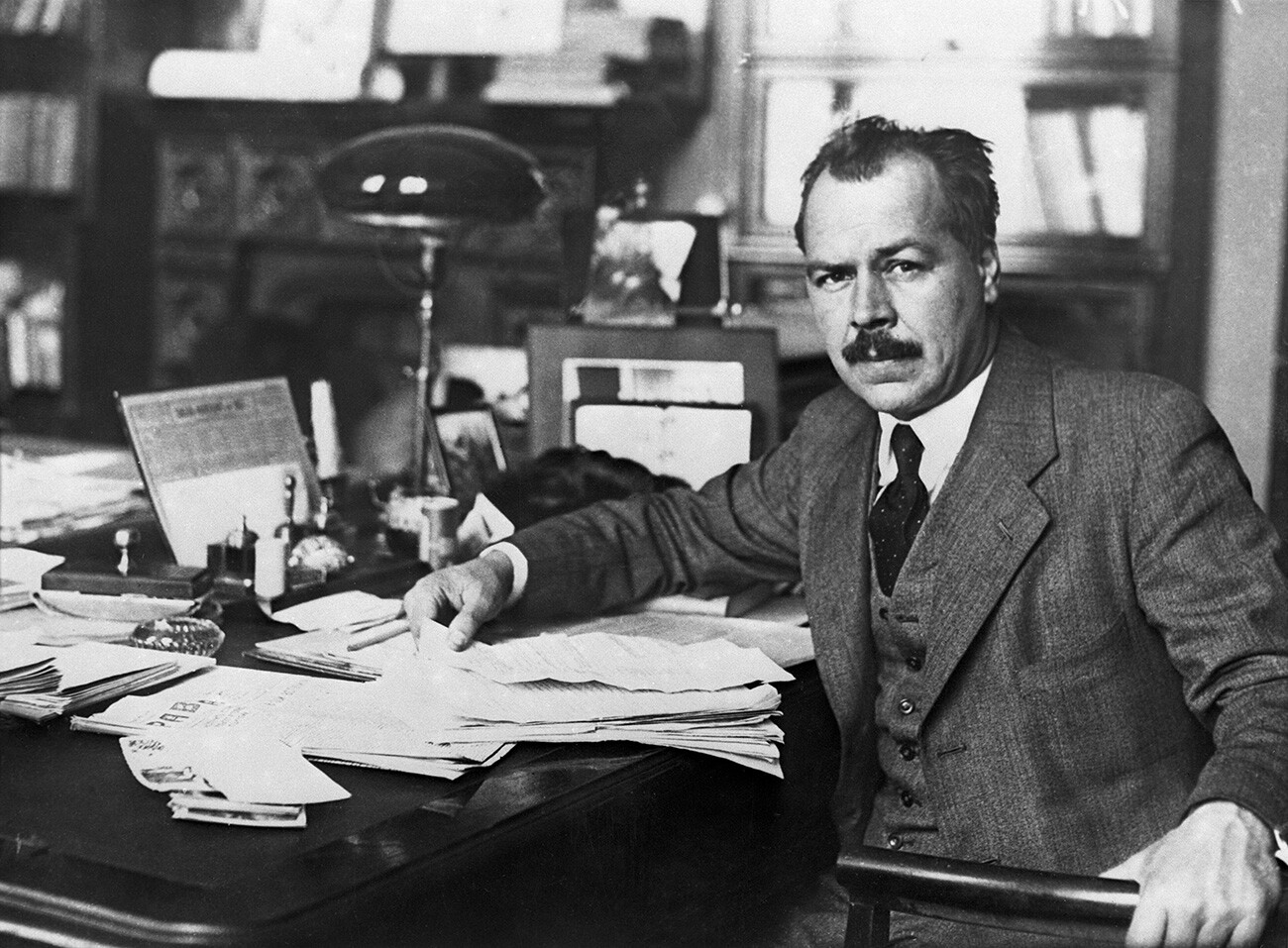

Scientist Nikolai Vavilov, who was the president of the Academy of Agricultural Sciences before Lysenko

Scientist Nikolai Vavilov, who was the president of the Academy of Agricultural Sciences before Lysenko

In 1955, almost 300 scientists signed a letter criticizing Lysenko; his theory was branded “medieval, bringing shame to Soviet science”. Lysenko was removed from his presidency in the Academy for a time, but, later, he was reinstalled by Khrushchev himself. The General Secretary supported Lysenko – he liked the peasant background of the scientist and his good wheat yields.

But, in 1965, after Khrushchev left, it was proven that Lysenko’s work contained academic violations and inaccurate arguments. He was finally removed from his position; however, he remained true to his ideas. He still had many followers and continued his experiments for 10 more years until his death; he also headed the laboratory of the ‘Leninskie Gorki’ experimental research base.

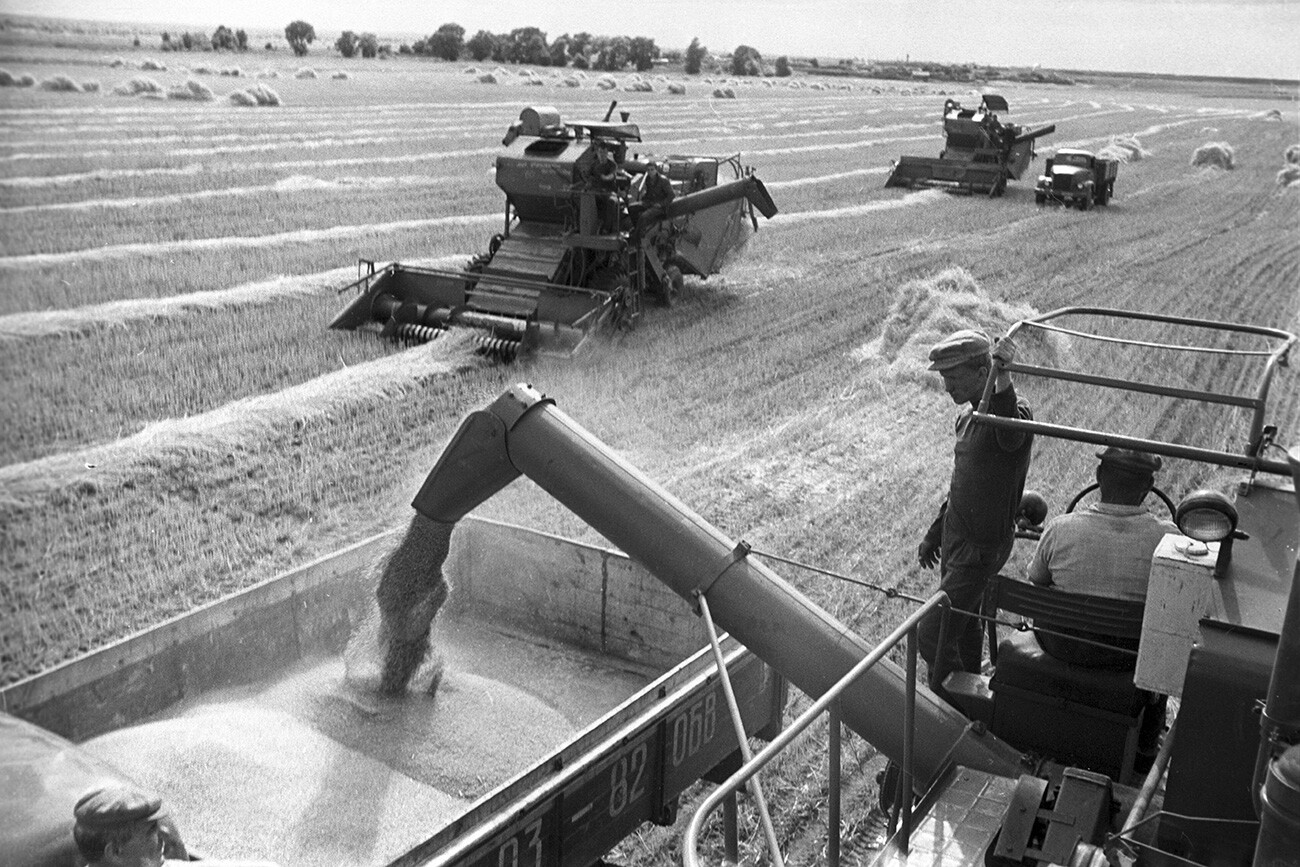

Wheat harvesting

Wheat harvesting