Irkutsk: Cultural crossroads in Eastern Siberia

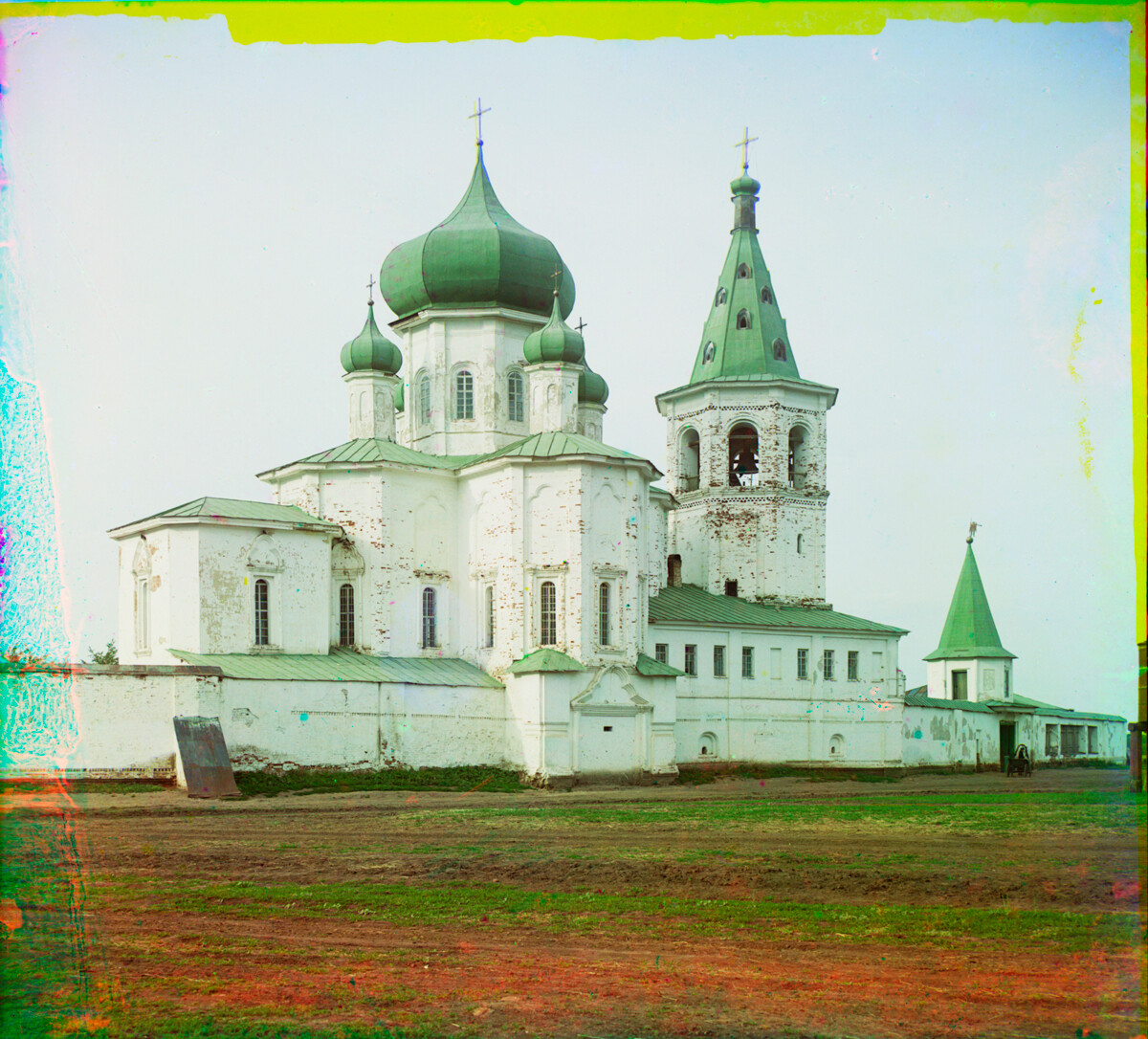

Irkutsk. Cathedral of the Epiphany & bell tower, southwest view. Second bell tower (right) completed in 1815 to support a locally cast 18-ton bell. August 31, 2000

Irkutsk. Cathedral of the Epiphany & bell tower, southwest view. Second bell tower (right) completed in 1815 to support a locally cast 18-ton bell. August 31, 2000

At the beginning of the 20th century, Russian chemist and photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for vivid color photography (see box text below). His vision of photography as a form of education and enlightenment was demonstrated with special clarity through his images of architectural monuments in the historic sites throughout the Russian heartland.

In June 1912, Prokudin-Gorsky ventured into western Siberia as part of a commission to document the Kama-Tobolsk Waterway, a link between the European and Asian sides of the Ural Mountains. The town of Tyumen served as his launching point for the journey north to Tobolsk, on the Irtysh River.

Tyumen. Trinity Monastery, Church of Sts. Peter and Paul, bell tower, south gate (1726-55). Southwest view. June 1912.

Tyumen. Trinity Monastery, Church of Sts. Peter and Paul, bell tower, south gate (1726-55). Southwest view. June 1912.

During his journey, Prokudin-Gorsky took fascinating photographs of both Tyumen and Tobolsk, with their 18th-century “Siberian Baroque” churches. Had he ventured farther eastward on the Trans-Siberian to the city of Irkutsk, he would have seen a still greater variety of ornamentalism in Siberian architecture.

One of a kind

For a dramatic natural setting, few Russian cities can rival Irkutsk. Located on the banks of the Angara River (a tributary of the Yenisei), Irkutsk is a major point on the Trans-Siberian railway and the gateway to sacred Lake Baikal, the deepest body of freshwater in the world. Because of its favorable geographic location, Irkutsk has attracted the resources to create a remarkable ensemble of historic architecture.

Russian settlements had existed in the Irkutsk area from the early part of the 17th century. A log fort was eventually constructed in 1661 at the confluence of the Angara and Irkut Rivers. The original purpose of the settlement was to establish Russian authority with the region's aboriginal Buryats. In 1686 it gained town status and shortly thereafter began sending caravans to China, which became a source of trade and cultural influence for Irkutsk.

Regional influence

Irkutsk. Church of Miraculous Icon of the Savior (1706-10, with bell tower added in 1758-62). Southeast view with large wall painting over apse. Image of Miraculous Icon of Savior on side of apse. October 3, 1999

Irkutsk. Church of Miraculous Icon of the Savior (1706-10, with bell tower added in 1758-62). Southeast view with large wall painting over apse. Image of Miraculous Icon of Savior on side of apse. October 3, 1999

By the beginning of the 18th century, Irkutsk was becoming the administrative and commercial center of a vast territory in central and eastern Siberia.

Irkutsk. Church of the Trinity (1754-75). Southeast view. Decorated with "Siberian Baroque" facade flourishes. October 2, 1999

Irkutsk. Church of the Trinity (1754-75). Southeast view. Decorated with "Siberian Baroque" facade flourishes. October 2, 1999

Its importance was reflected in several large masonry churches, profusely decorated in forms that combined Russian and Ukrainian influences with the building traditions of the Russian north and the Urals such as Solikamsk.

Convent of Icon of the Virgin of the Sign (Znamenye) with south gate & Cathedral of Icon of the Sign (1757-62). October 3, 1999

Convent of Icon of the Virgin of the Sign (Znamenye) with south gate & Cathedral of Icon of the Sign (1757-62). October 3, 1999

Early 18th-century monuments include the Church of the Miraculous Icon of the Savior, with its distinctive exterior frescoes in the manner of Veliky Ustyug, and the brightly painted Cathedral of the Epiphany, begun in 1718 and expanded over the course of a century.

Cathedral of Icon of Virgin of the Sign (1757-62). View east toward the icon screen. October 4, 1999

Cathedral of Icon of Virgin of the Sign (1757-62). View east toward the icon screen. October 4, 1999

Merchant influence & architectural growth

By the middle of the 18th century, Irkutsk advanced to a new level of commercial importance. The majority of its population was involved in entrepreneurial activity of one form or another and its merchants assumed an increasingly important role in guiding the city in the absence of an established local nobility. This surge of economic vitality gave rise to a rich urban silhouette created by the vertical accents of church cupolas and towers.

The most remarkable of these new buildings is the Church of the Elevation of the Cross (also known as the Trinity), built between 1747 and 1760 on the Hill of the Cross.

Church of the Elevation of the Cross (1747-60). North view with bell tower. September 5, 2000

Church of the Elevation of the Cross (1747-60). North view with bell tower. September 5, 2000

From the bell tower and steeple over the west end to its panoply of Baroque domes over the main structure in the east, this church remains to this day a dominant presence in the southern part of historic Irkutsk.

Church of the Elevation of the Cross. North facade with distinctive terracotta decorative elements. September 5, 2000

Church of the Elevation of the Cross. North facade with distinctive terracotta decorative elements. September 5, 2000

The design of the Church of the Elevation of the Cross displays the influence of central Russian and Ukrainian church architecture on the exterior as well as the interior.

Church of the Elevation of the Cross. South facade with terracotta decorative elements including symbolic figure with heart. October 3, 1999

Church of the Elevation of the Cross. South facade with terracotta decorative elements including symbolic figure with heart. October 3, 1999

Furthermore, its stylistic range extends to Asian sources as revealed in the carefully restored facade ornamentation. Of particular note are intricate stupa-like forms in terra cotta framing the north and south portals. It is likely that the active trade between Irkutsk and China played a role in this cross-cultural work of art.

Church of the Elevation of the Cross. View east toward the icon screen. October 4, 1999

Church of the Elevation of the Cross. View east toward the icon screen. October 4, 1999

Irkutsk also had churches in the neoclassical style, yet its most refined example of neoclassical architecture is the imposing mansion built for Ksenofont Sibiryakov, a merchant who had successfully tapped the great wealth of Siberia and its fur trade.

Ksenofont Sibiryakov mansion (1800-04). From 1837-1917 residence of Governor-General of Eastern Siberia. October 3, 1999

Ksenofont Sibiryakov mansion (1800-04). From 1837-1917 residence of Governor-General of Eastern Siberia. October 3, 1999

The mansion, now used as the central building of Irkutsk University, can be compared with mansions in Moscow during the same period.

Wooden origins

Sergei Volkonsky house. September 2, 2000

Sergei Volkonsky house. September 2, 2000

Until the 20th century, housing in Irkutsk was largely built of wood. Among the earliest surviving examples of wooden houses are those belonging to Sergei Trubetskoy (1790-1860) and Sergei Volkonsky (1788-1865), members of the noble elite who were exiled to Siberia for their role in an uprising against tsarist authority in December 1825.

Sergei Trubetskoy house. September 2, 2000

Sergei Trubetskoy house. September 2, 2000

Later, examples of wooden houses in Irkutsk show a more ornate “merchant style” with elaborately carved decorations comparable to examples in other Siberian cities, such as Tomsk and Chita.

Shastin house. One of best examples of Siberian decorative wooden architecture. Core of house built around 1840 with later expansion. In 1907 bought by Apolos Shastin who added second floor & gave the house its decorative panoply. Background: Church of Transfiguration. October 3, 1999

Shastin house. One of best examples of Siberian decorative wooden architecture. Core of house built around 1840 with later expansion. In 1907 bought by Apolos Shastin who added second floor & gave the house its decorative panoply. Background: Church of Transfiguration. October 3, 1999

A catastrophic fire in 1879 destroyed much of Irkutsk, including masonry buildings as well as wooden houses. Nonetheless, the town soon rebounded on the strength of gold mining and growing trade, both domestic and foreign.

Like other Siberian cities, Irkutsk in the late 19th century was a town of various faiths. In 1875 work began on one of the largest Russian Orthodox cathedrals, dedicated to the Kazan Icon of the Virgin (consecrated in 1894). Ten years later, work began on another shrine dedicated to the Kazan Icon of the Virgin, and it still stands – unlike the larger Kazan Cathedral in the center of Irkutsk.

Cathedral of Kazan Icon of the Virgin (1885-92). South view. Built in massive Russo-Byzantine style with unusual facade coloration. October 3, 1999

Cathedral of Kazan Icon of the Virgin (1885-92). South view. Built in massive Russo-Byzantine style with unusual facade coloration. October 3, 1999

Nearby, the sizable local Catholic parish (primarily ethnic Poles and Lithuanians) rebuilt the Church of the Assumption in the early 1880s.

Catholic Church of the Assumption of Our Lady. West view. August 31, 2000

Catholic Church of the Assumption of Our Lady. West view. August 31, 2000

Irkutsk also gained a new synagogue, built in 1881-1882 by Vladislav Kudelsky.

Irkutsk Synagogue. October 3, 1999

Irkutsk Synagogue. October 3, 1999

The Irkutsk Muslim population had its place of worship, constructed at the turn of the 20th century.

Urban future

Irkutsk City Theater. September 1, 2000

Irkutsk City Theater. September 1, 2000

During this period, Irkutsk was transformed by an array of office buildings, hotels, banks and theaters. The most impressive public structure in Irkutsk at the end of the 19th century was the City Theater, built in 1894-1897 and splendidly restored a century later. These major buildings reflect an economic stimulus created in part by the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

Irkutsk City Theater. View from stage toward loges & balconies. September 1, 2000

Irkutsk City Theater. View from stage toward loges & balconies. September 1, 2000

As elsewhere in Siberia, these promising developments were shattered after 1914 by seven years of conflict, including fighting among various Red and White factions during the Russian Civil War. In 1932 the Cathedral of the Kazan Icon was demolished, and the regional administrative headquarters was built on the site. Closed in 1938, the Catholic Assumption Church was eventually converted to a concert hall after restoration work in the 1970s.

Vtorov Building (1897). Built as an emporium by renowned Siberian merchant Alexander Vtorov. Since 1936, Palace of Children's Creativity (Zhelyabov Street 5). September 4, 2000

Vtorov Building (1897). Built as an emporium by renowned Siberian merchant Alexander Vtorov. Since 1936, Palace of Children's Creativity (Zhelyabov Street 5). September 4, 2000

Other Orthodox churches and chapels were destroyed or damaged during the Soviet period, but those remaining have been carefully restored over the past few decades. The role of central shrine of Irkutsk Eparchy has been returned to the original Epiphany Cathedral, whose interior is adorned with new frescoes.

Cathedral of the Epiphany. Refectory interior, view east with new frescoes. September 1, 2000

Cathedral of the Epiphany. Refectory interior, view east with new frescoes. September 1, 2000

Irkutsk – now and beyond

After unsuccessful negotiations in the 1990s over the return of the Assumption Church to the revived Catholic parish, an agreement was reached that allowed the Diocese of Irkutsk to build a cathedral in an area near the Irkutsk State Technical University. Begun in 1999, the strikingly modern Cathedral of the Immaculate Heart of the Virgin Mary was consecrated in 2000. It also provides a venue for concerts of organ music.

Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Heart of the Virgin Mary. View soon after consecration with evening sun rays streaming through tower over main entrance. September 7, 2000

Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Heart of the Virgin Mary. View soon after consecration with evening sun rays streaming through tower over main entrance. September 7, 2000

Today, Irkutsk (population 611,000) has preserved in its central part much of the ambiance created during the commercial and building expansion at the beginning of the 20th century. As one of the leading cultural, educational and industrial centers of eastern Siberia, as well as the gateway to Lake Baikal, Irkutsk has ample reason to protect the rich cultural legacy of its historic architecture.

Wooden house with decorative windows, Barricade Street 73. October 3, 1999

Wooden house with decorative windows, Barricade Street 73. October 3, 1999

In the early 20th century, Russian photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916, he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France, where he was reunited with a large part of his collection of glass negatives, as well as 13 albums of contact prints. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century, the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A few Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986, architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles juxtaposes Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.