5 facts about Pskov-Caves Monastery, one of Russia’s most famous

1. The monastery was founded in caves

Dormition Cave Church

Dormition Cave Church

The name of the monastery Pskov-Caves hints to us that the monastery has caves. ‘Pechory’ translates as ‘caves’ in English. Perhaps, they may have appeared naturally. The first monks began to live inside them, burying the dead right there, underground.

Church of Saint Michael the Archangel

Church of Saint Michael the Archangel

It is not known exactly who first settled there and when. According to one version, the monks of the Kiev-Caves monastery (also a cave monastery) fled there, to the north, from the Crimean Tatar raids.

Ensemble of the Pskov-Pechersk Monastery with belfry

Ensemble of the Pskov-Pechersk Monastery with belfry

The date of foundation of the Pskov-Caves Monastery is considered to be 1473, when monk Jonah dug the first cave church devoted to the Dormition of the Mother of God. Over time, the brethren greatly expanded the caves and, now, they are real underground labyrinths that stretch for many kilometers. And the relics of the saints have been preserved in them.

2. A fortress that took part in battles

Domes of the Intercession Church

Domes of the Intercession Church

The monastery was (and still is) on the westernmost frontier of Russia – along the way to the ancient city of Pskov. That is why it was attacked from the West more than once. Mostly the monks were disturbed by the knights of the Livonian Order. Their castle Neuhausen was only 20 kilometers away from the monastery.

The monastery wall

The monastery wall

In the 16th century, powerful stone walls were erected around the monastery. The new fortress was besieged many times: by Polish king Stefan Batory, by interventionists during the ‘Time of Troubles’ and by Lithuanian detachments until the early 18th century.

3. The only Russian monastery that has never been closed down

In 1920, under a peace treaty, Soviet Russia ceded the Pechora District of Pskov Oblast, including the monastery, to Estonia. In fact, this saved the cloister. After all, by the late 1920s, the Soviet authorities had closed all the monasteries in Russia. And, under the jurisdiction of Estonia, the Pskov-Caves Monastery was not closed.

Picturesque fall scenery

Picturesque fall scenery

Twenty years later, Estonia became a part of the USSR. But, it was already during World War II, when the Soviet authorities had more important things to do than to close monasteries. Moreover, very soon, these places fell under the Nazi occupation zone. And the monastery came under fire several times.

After the war, several monks and an abbot of the monastery were arrested and convicted for complicity with the occupiers.

The aerial view of the monastery

The aerial view of the monastery

For many years after the war, only two monasteries operated in Russia. They were the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, which closed in the 1920s, but was allowed to reopen in the 1940s and the Pskov-Caves Monastery, which was never once closed.

4. A place known for its holy elders

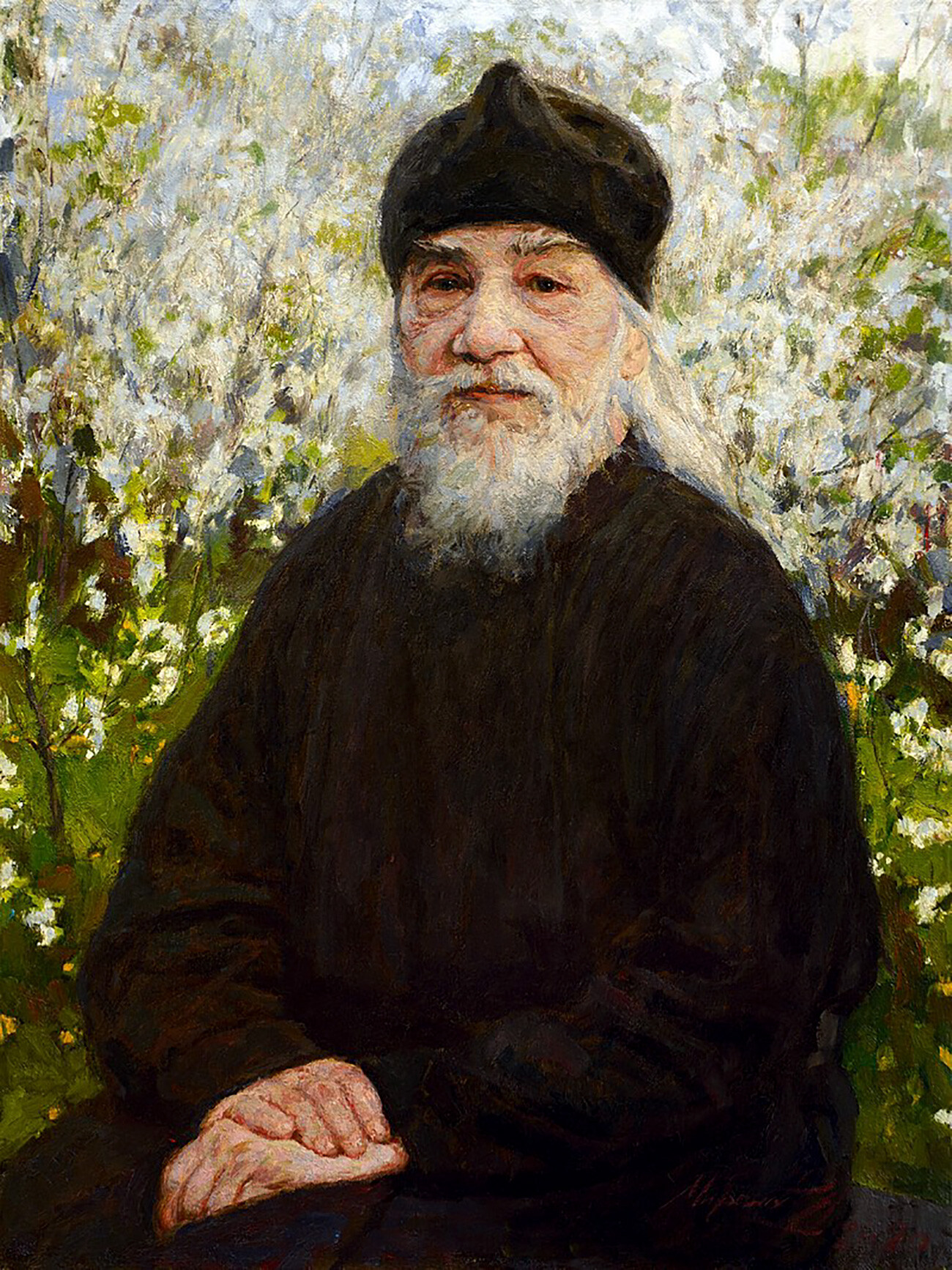

A monk of the Pskov-Caves Monastery

A monk of the Pskov-Caves Monastery

There are many legends about the abbots and monks of the monastery. It is believed that the monks of the Pskov-Caves Monastery were characterized by extraordinary obedience and real monastic feats.

Many relics have been preserved in the caves, starting with the founder – St. Jonah. The real heyday of the monastery happened under the abbot Cornelius in the 16th century. It is believed that Cornelius was killed by order of Ivan the Terrible and then canonized by the Church as a martyr monk.

John (Krestiankin)

John (Krestiankin)

Over the long history, there were many more monks who performed legendary miracles. But, the most famous in our time is Archimandrite John (Krestyankin). He became a priest in the 1940s, when it was still very dangerous. Upon denunciation, he was arrested and spent three years in the northern Gulag camps. After release, he served in several monasteries, but did not take root anywhere, until he came to the Pskov-Caves Monastery.

There, he was a monk for more than 40 years until his death. He was honored as a saint for his wisdom and high spirituality even during his lifetime and believers came to him from all over the country. Every day, he received many people, helping some with advice and blessing others.

Read more about the phenomenon of the Russian elders, a.k.a. ‘startsy’.

5. Monastic life is described in the book ‘Everyday Saints’ by Tikhon Shevkunov

Metropolitan Tikhon

Metropolitan Tikhon

Present Metropolitan of the Russian Orthodox Church Tikhon (Shevkunov) began his monastic path in the Pskov-Caves Monastery. He personally met elder John (Krestiankin) and other revered monks. And he described the everyday life of the holy places in his book, a best selling short stories collection, titled ‘Everyday Saints and Other Stories’, which was translated into many languages, including English.

There are some funny episodes in the book. For example, about the monks' relationship with the Soviet authorities and how the brethren would attend Soviet elections (Read more here).

Church procession in the monastery, 1988

Church procession in the monastery, 1988

Bishop Tikhon also reveals unexpected details, for example, that more than half of the monks were veterans of World War II.