How did the Mariinsky Theater survive the Nazi siege of Leningrad?

On September 19, 1941, a 250-kilogram high-explosive bomb hit the building of the Kirov State Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet (as the Mariinsky Theater was known in Soviet times). It destroyed the seating area of the theater, but the wounds it left in the hearts of the people of Leningrad were even more painful; and not just among those who worked there. Then, just as now, the Kirov Theater was (and still is) a symbol of the city, its imperial era culture, and the newest Soviet achievements.

The theater after bombing, 1941

The theater after bombing, 1941

The majority of the theater workers, however, didn’t hear right away about what had happened. In the middle of August they had been sent in two train echelons deep into the country’s interior, to the Urals. The packing was done in haste; few realized that they were leaving for years – many believed that the valiant Red Army would be quick to expel the Nazi invaders.

Arriving in the city of Molotov

After nine days on the road, the train echelons stopped in the city of Molotov – as Perm was then called. No one was there waiting for the theater refugees; the city was already filled to the brim with evacuated people. “Having not even managed to get accommodated, we all rushed to the theater. It disappointed us: the stage was almost a fourth of the size of ours in Leningrad,”’ Tatiana Vecheslova, the theater’s principal dancer, remembered.

From the very beginning, it was clear that they had to make new decorations – the ones brought from Leningrad were simply impossible to fit on a new stage. To fit in the orchestra, the first rows of the parterre seats had to be removed. By September 13, however, the performers from Leningrad opened the season in their new home.

The same Vecheslova testified: “The first performance at the theater opening – Ivan Susanin (in which I danced a waltz) – went on quietly, without success. Neither the incredible play of the orchestra conducted by A. Pazovsky, nor the beautiful young voices of N. Kashevarova, G. Nelepp, and I. Yashugin could melt the ice in the audience.

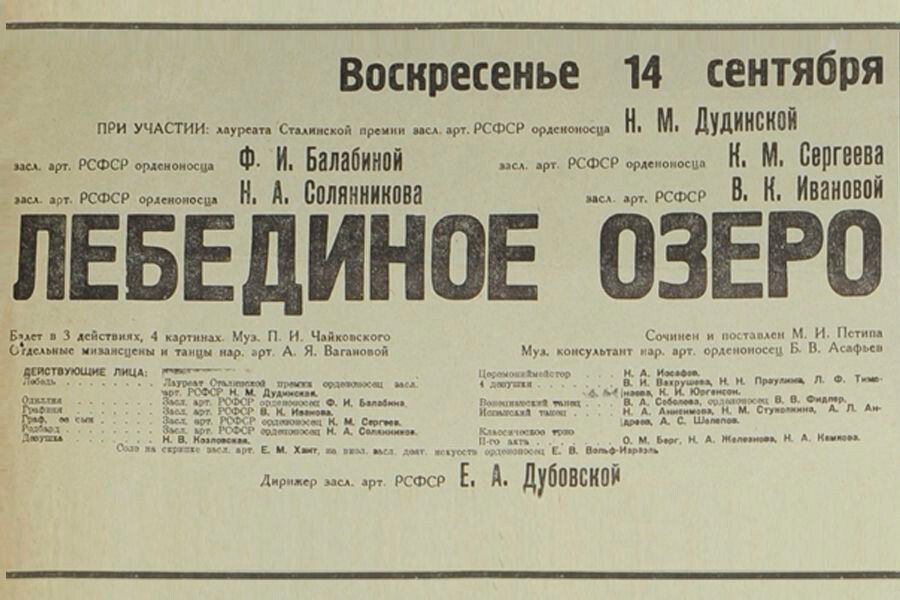

A fragment of a September 1941 poster promoting the 'Swan Lake' ballet

A fragment of a September 1941 poster promoting the 'Swan Lake' ballet

As the evacuation continued, the city gave shelter to more and more people, but it seemed that few were interested in theater. “The situation also didn’t change after the next performance – Swan Lake. ‘Who needs our ballet?’ we thought. Blood was spilling, the cities of our homeland are being surrendered to our enemy one after another, refugees sit around on train stations for weeks, while we are supposed to dance and try and prove that someone needs our art!”

The intellectual center of the Urals

A scene from 'Ivan Susanin' opera staged in Perm

A scene from 'Ivan Susanin' opera staged in Perm

At this time, Perm hadn’t yet discovered the art of opera and ballet for itself. The troupe of its own local opera theater had been formed just shortly before the war. With the arrival of the Leningrad theater, the local theater was forced to go on a tour for several years to the small cities and villages of the region, performing in clubs, sheds, or sometimes even simply on trucks put close together and which were entirely unfit for performances.

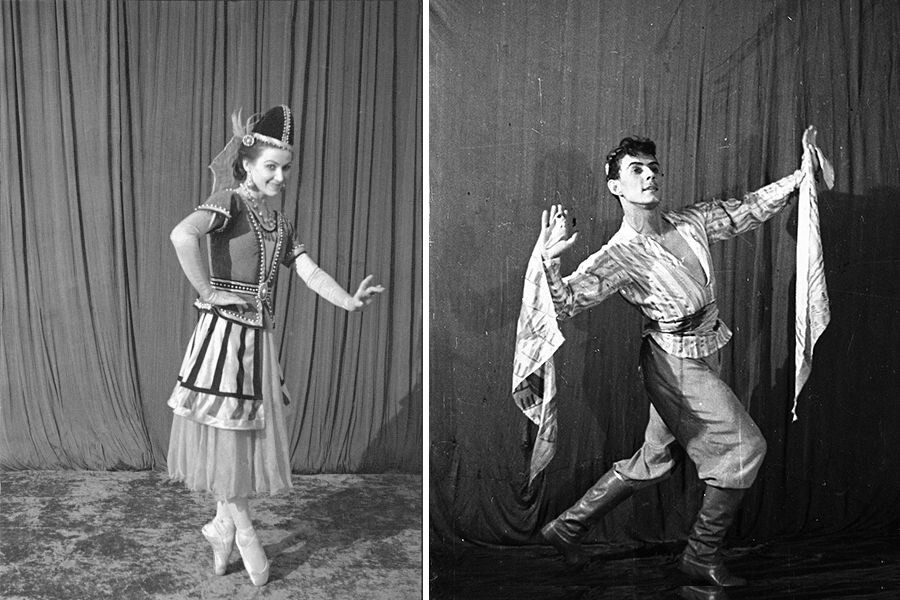

The people of Leningrad also didn’t find it easy for themselves. As conductor Yuri Gamaley remembered, the dancers had to “do not so much as long jumps but high jumps”, adapting themselves to the size of the stage. To physically survive, the leading bass of the troupe, Ivan Yashugin, worked as a loader for additional food. However, slowly, with the help of the Leningraders, the people of Perm discovered opera and ballet. After just a few months, the theater hall began filling to the brim.

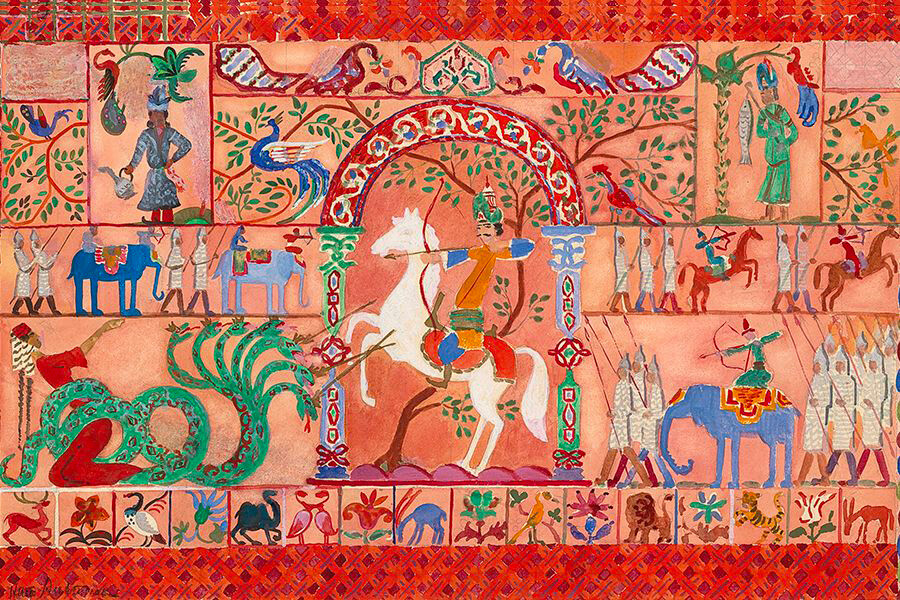

Nathan Altman. Sketch of a canopy for the ballet "Gayane"

Nathan Altman. Sketch of a canopy for the ballet "Gayane"

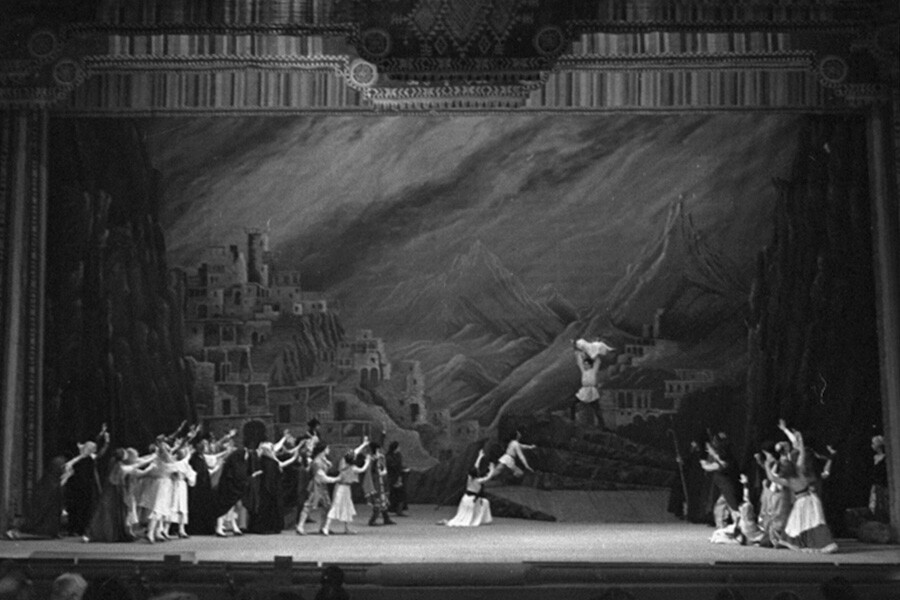

During their time in evacuation, the Kirov Theater managed to bring back to the stage about 20 performances, as well as release several premieres, among which was Aram Khachaturian’s ballet Gayane, which he finished in Perm. Khachaturian, as well as the main group of the workers of the troupe, settled in the ‘seven-story building’, a hotel built in the Constructivist style right next to the theater.

A scene from the "Gayane" ballet

A scene from the "Gayane" ballet

During these years it became a true intellectual center: Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev, Ivan Sollertinsky, Agrippina Vaganova, Galina Ulanova, and many others stayed in this hotel. After some time, there also appeared an exhausted, starved woman, in whom people could barely recognize the beauty from the portraits by Zinaida Serebriakova – Ekaterina Heidenreich, one of the brilliant ballet soloists of the Russian Empire. She had ended up in the Gulag in the first months of the war after someone denounced her for expressing doubts that the USSR would manage to hold Leningrad.

Tatiana Vyacheslova and Nikolai Zubkovsky in costumes of the "Gayane" ballet

Tatiana Vyacheslova and Nikolai Zubkovsky in costumes of the "Gayane" ballet

Somehow, she managed to be freed from the camp, and she began giving ballet lessons to local kids. Later, when the siege was broken, she wasn’t allowed to return back home with the others. She stayed in Perm and became the founder and the first director of the Perm State Choreographic College.

Ballet during the Siege

At this same time, opera and ballet performances continued at the Kirov in Leningrad. Not all the artists were able to be evacuated in the August rush, and soon the Nazis sealed off the city. After a bomb hit the theater, performances and concerts had to be held elsewhere.

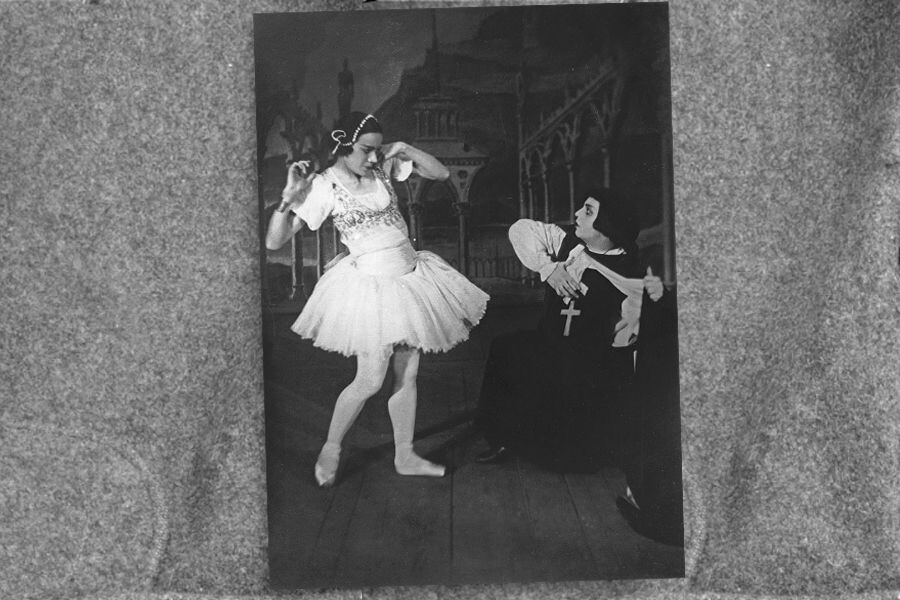

Olga Iordan as Esmeralda in the scene of "La Esmeralda" ballet, 1942–1943

Olga Iordan as Esmeralda in the scene of "La Esmeralda" ballet, 1942–1943

Responsibility for running the theater fell onto the shoulders of singer Ivan Nechaev and principal ballet dancer Olga Jordan. Due to the intense air raids and bombings, performances were conducted during the day; but even they were endlessly interrupted by air alarms. Struck by the fact that the audience didn’t leave the hall, at times the performers didn’t stop their performances either.

With the coming of the first horrifying siege winter the theater life ended – the city’s electricity and water supply ceased to function, and the daily bread norm dropped to 250 grams for the working people. Mass deaths from starvation began. In March, however, performances resumed. And they were not modest one-act plays. While the artists were all skin and bones, they revived The Queen of Spades, Eugene Onegin, La Traviata, Esmeralda, and Carmen for the people of Leningrad.

A scene from the "Esmeralda" ballet, 1942

A scene from the "Esmeralda" ballet, 1942

At that time the young Galina Vishnevskaya took a seat in the audience, watching an opera performance for the first time. Later, in her memoirs, she wrote: “The entire performance burned into my memory like onto a filmstrip. I can see before me exhausted German, Liza with bare, blue, and skinny shoulders like that of a skeleton, with a thick layer of white powder on them; the great Sofya Preobrazhenskaya – the countess (I’d never hear such a dramatic mezzo-soprano in my life again) - was in the prime of her talent. When they sang, people could see their breath pouring like clouds out of their mouths.

Opera singer Sofya Preobrazhenskaya, 1940s

Opera singer Sofya Preobrazhenskaya, 1940s

“The excitement, the shock I sat through there, was not just my enjoyment of the performance: that was the feeling of pride for my resurrected people, for the great art that forced all these half-dead – the orchestra musicians, the singers, the audience – to unite in this hall, beyond the walls of which an air raid alarm blares and shells explode. Truly – man lives not by bread alone.”

According to estimates, over the three years of the Nazi siege, about a hundred thousand viewers saw opera and ballet performances in Leningrad. Ballet soloist Natalia Sakhnovskaya, who kept a diary throughout the entire siege, wrote after a concert: “It seemed that never before have we danced with such pleasure, never have we felt such completeness of our delivery. Kind faces and a warm welcome were our reward…”

The theater's artists reading Pravda newspaper with new about the siege breakthrough

The theater's artists reading Pravda newspaper with new about the siege breakthrough