Eisenstein abroad: Tennis with Chaplin, a spat with Stalin and an unfinished film about Mexico

In December 1925, film director Sergei Eisenstein wrote in his diary: "I woke up to find myself famous". This was on the occasion of his film “Battleship Potemkin” having its triumphant debut on Moscow screens, setting a qualitatively new bar for cinema. "The audience rose to their feet and gave our film an ovation. The orchestra stopped playing - you couldn't hear anything anyway. The musicians joined the whole audience in cheering the picture," is how Grigori Aleksandrov, Eisenstein's assistant, remembered the film's premiere.

“Potemkin” was an ode to the Russian Revolution. The film director wholeheartedly supported the Bolsheviks and more than once admitted that the events of October 1917 had determined his destiny and in many ways shaped his creative ideas.

During the filming of “Battleship Potemkin”

During the filming of “Battleship Potemkin”

“Battleship Potemkin” was distributed abroad and the revolutionary film by the Soviet director took the whole world by storm. King Gustaf V of Sweden greeted the picture with enthusiastic applause at its Berlin premiere. Charlie Chaplin described it as the best film he had ever seen. And even Joseph Goebbels, minister of propaganda of the Third Reich, later admitted: "It is a marvelous film without equal in the cinema… anyone who had no firm political conviction could become a Bolshevik after seeing the film."

But the ideological component of the film was a problem for other countries. The German government was unhappy with the film’s huge success glorifying the Revolution, and soon enough the Reichstag received a recommendation that Eisenstein's picture should be banned for "glorifying violence, stirring up discontent against the authorities and inciting the masses".

The government did not adopt the recommendation, however, fearing that banning the film would draw even more attention to it. In Britain, widespread miners' strikes were taking place at the time, so “Potemkin” was not distributed at all there. This didn't stop the film from enjoying a huge success in bootleg markets, however.

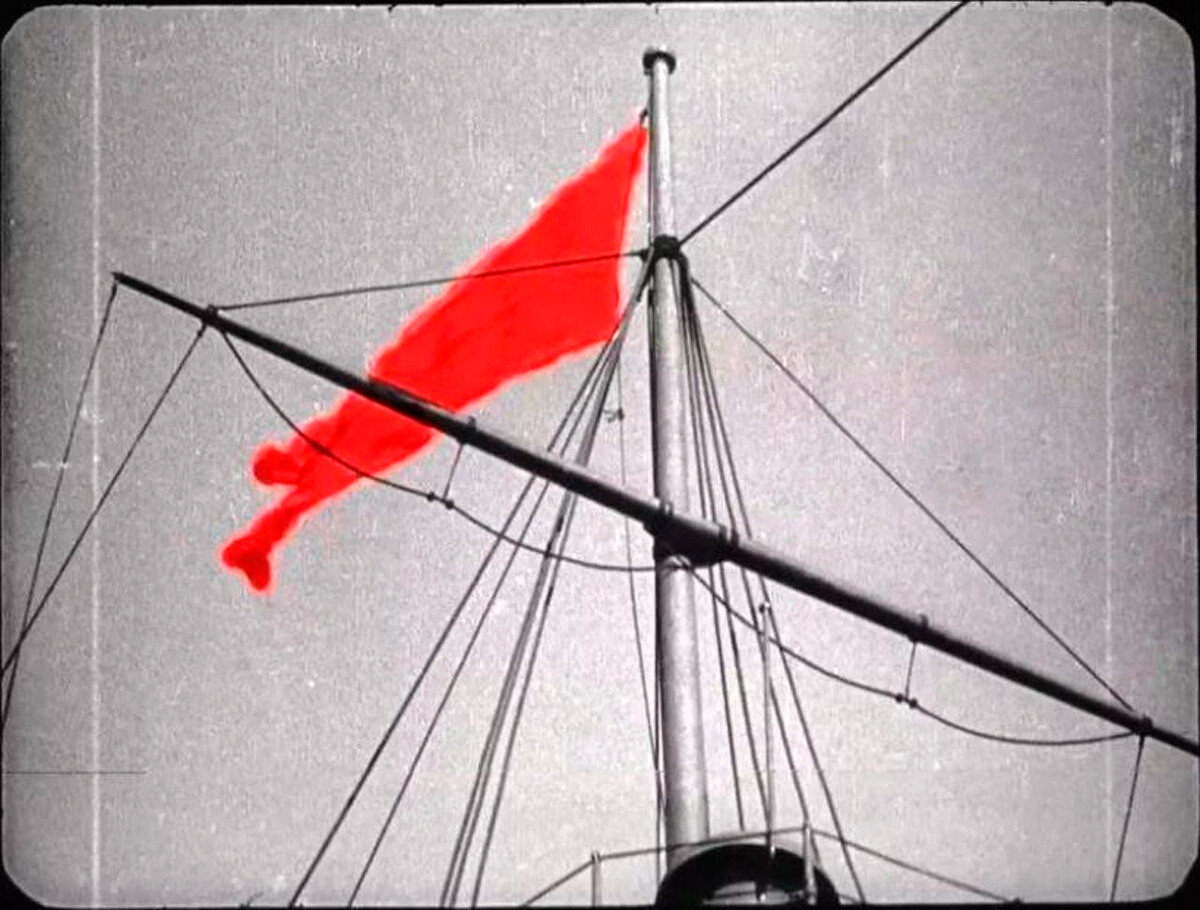

Still from “Battleship Potemkin”

Still from “Battleship Potemkin”

In any case, after “Battleship Potemkin” cinema began to be treated as an art form and Eisenstein himself became the world’s most fashionable film director.

The next revolution in cinema, however, happened in the U.S. when the Americans learned to make talking pictures. And Eisenstein, more than anyone else, realized that sound must also be urgently introduced into Soviet films. The idea of going to Hollywood to study the experience of Western colleagues fired his imagination. To be able to do this, he managed to get a personal meeting with Stalin and in 1929, after finishing filming “Old and New” (also known as “The General Line”), he was granted permission to travel abroad.

Stuck in Europe

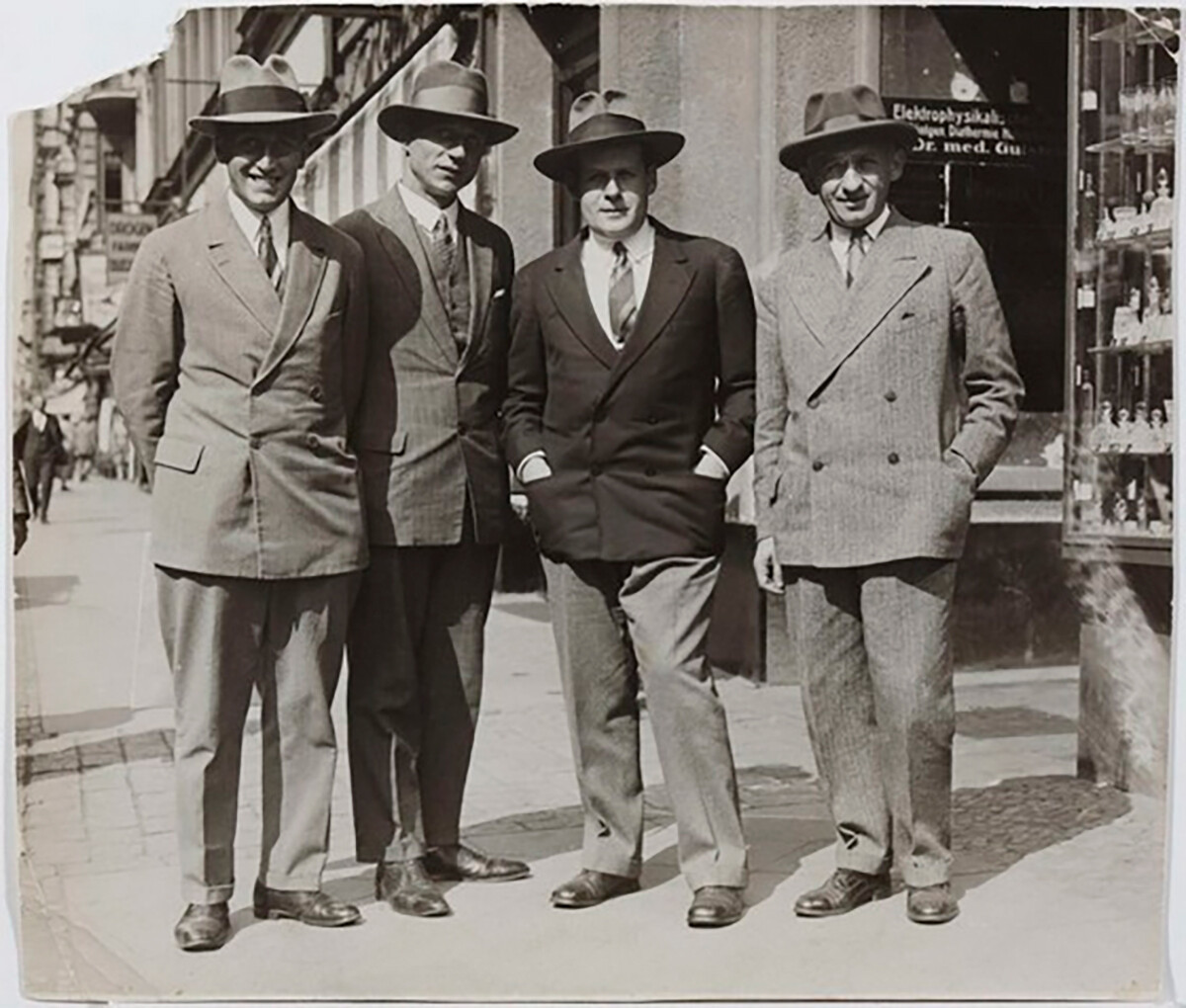

Grigori Aleksandrov, Eduard Tisse, Sergei Eisenstein and Julian Kaufman in Berlin, 1929

Grigori Aleksandrov, Eduard Tisse, Sergei Eisenstein and Julian Kaufman in Berlin, 1929

Eisenstein set off on his foreign trip in the company of his assistant Grigori Aleksandrov and regular cameraman Eduard Tisse. Berlin was the first stop on the journey to Hollywood. It was impossible at the time to obtain an American visa in Moscow because of the absence of official diplomatic relations between the U.S. and USSR.

The American government, vehemently anti-Communist, only recognized the Soviet Union in 1933. Eisenstein had previously received an invitation to come to the U.S. from United Artists, but on arriving in Berlin and contacting the film company, he was sent a cable with the words: "Your trip to the U.S. is unfeasible at the present time." Eisenstein's group ended up spending over half a year in Europe.

The director traveled between European cities giving lectures on cinema theory and Soviet films. Berlin, Hamburg, Zurich, London, Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam, Antwerp - the geography of the Soviet cinematographers' travels expanded as rapidly as the circle of Eisenstein's new acquaintances. He met some of the most illustrious filmmakers and writers of the time - George Bernard Shaw, James Joyce, Béla Balázs, Léon Moussinac, George Bancroft and Josef von Sternberg. Everyone wanted to meet the director of the great “Battleship Potemkin”.

Sergei Eisenstein, George Bancroft, Emil Jannings, Josef von Sternberg. Berlin, 1929

Sergei Eisenstein, George Bancroft, Emil Jannings, Josef von Sternberg. Berlin, 1929

While delivering his talks, Eisenstein, an enthusiastic supporter of the Russian Revolution, made no effort to conceal his political predilections. This alarmed the leaders of the countries that the Soviet film director visited. After a series of lectures in a working class district of Zurich, the Swiss police forced Eisenstein to leave the country. The director also tried to arrange the dubbing of the film “The General Line” (also known as “Old and New”) in France and Britain, but he could not find the financing for it.

In the course of his extended trip to Europe, Eisenstein regularly needed to undertake commercial projects in order to earn money to buy a crust of bread and pay for the roof over his head. For instance, his group shot the short film “Sentimental Romance” with money provided by the Parisian jeweler Léonard Rosenthal. The businessman only agreed to finance the picture on condition that his mistress, Mara Griy, played the lead role.

Thanks to this work, Eisenstein, Aleksandrov and Tisse received not just a generous fee but also the chance of working on a film with sound. “Sentimental Romance” was the first sound film in the director's career, though the reviews it received were mixed.

Grigori Aleksandrov during the filming of “Sentimental Romance”

Grigori Aleksandrov during the filming of “Sentimental Romance”

Eisenstein was also required to inform Moscow of his movements and to send cables to the Soviet press. There was always the danger of his becoming a "non-returnee" - a Soviet citizen who went abroad and severed all ties with the USSR. Eisenstein did all he could to give the impression that he was in Europe as a representative of the Soviet Union, and not as an independent film director.

It was only in late April 1930 that Eisenstein's dream of going to Hollywood finally became a reality. He signed a contract with Paramount, obtained an American visa and set off for the U.S. The director hoped to make several films, alternating locations between the USSR and Hollywood. This was extremely naive on his part.

"Reds" in America

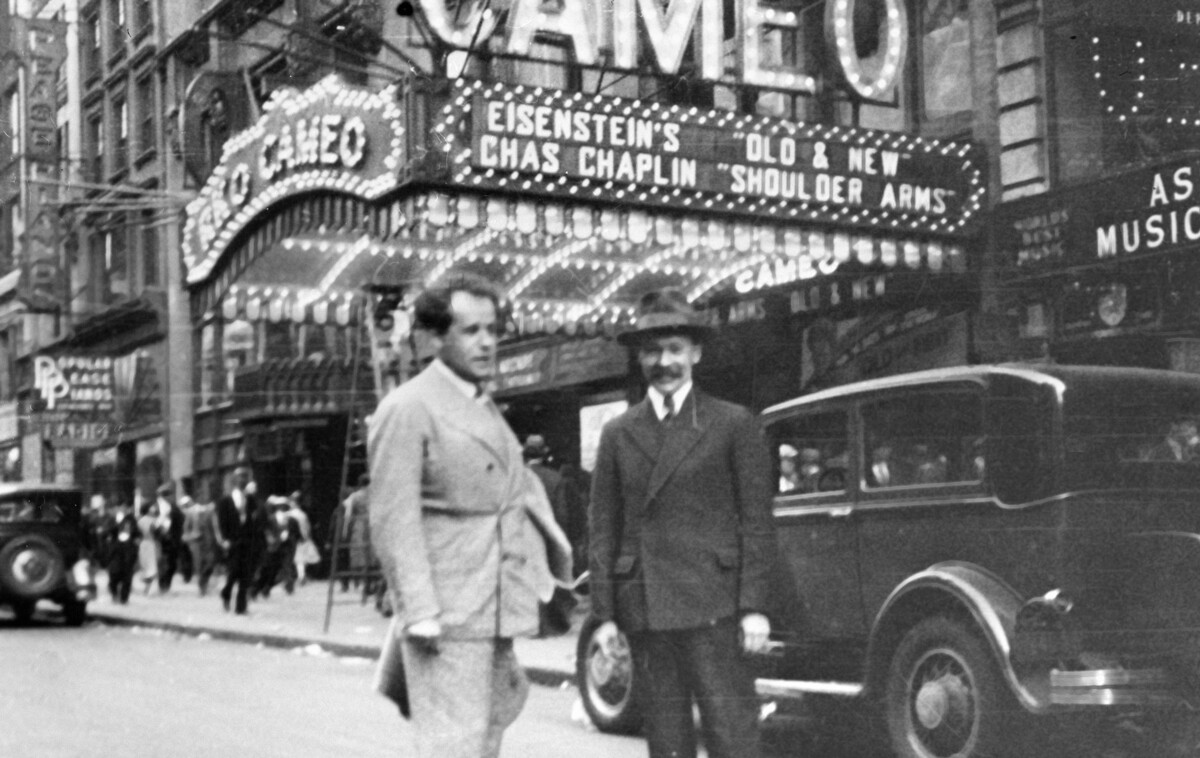

Sergei Eisenstein in New York

Sergei Eisenstein in New York

One of the first people that the Soviet filmmakers met in the U.S. was Charlie Chaplin, the superstar of silent cinema. Upon hearing that the group led by Eisenstein had come to Hollywood to learn about talking pictures, he burst out laughing: "In Hollywood they don't make films, they make money. The art of cinema should be learned where 'Battleship Potemkin' was made." The story was recounted by Grigori Aleksandrov in his 1983 book The Epoch and Cinema.

Eisenstein was a frequent visitor to Chaplin's villa. Almost every day they played tennis, swam in the pool and spoke a lot about cinema. The Soviet director thought that Charlie and he were very similar. Both were notable for their inquiring mind, they were both workaholics and had something of a quick-tempered and truculent child about them.

The only thing that worried Eisenstein was that he didn't understand why Chaplin was leading a dull Hollywood life. At social gatherings film stars always discussed the same things - property, money, gossip and bridge. He saw nothing interesting in such a way of life, and wanted to give the appearance of being the exact opposite of all this.

Sergei Eisenstein and Charlie Chaplin playing tennis

Sergei Eisenstein and Charlie Chaplin playing tennis

Eisenstein also visited the film studio of Walt Disney, about whom he subsequently wrote with admiration on more than one occasion: "I am sometimes frightened when I watch his films. Frightened because of some absolute perfection in what he does. This man seems to know not only the magic of every technical means, but also all the most secret strands of human thought, images, ideas, feelings… He creates on the conceptual level of man not yet shackled by logic, reason, or experience… One of Disney’s most amazing films is his 'Merbabies'. What purity and clarity of soul is needed to make such a thing! To what depths of untouched nature is it necessary to dive with bubbles and bubble-like children in order to reach such absolute freedom from all categories, all conventions. In order to be like children." (Eisenstein on Disney, ed. Jay Leyda. Calcutta: Seagull Books, 1986, p. 2)

Sergei Eisenstein and Walt Disney, 1930

Sergei Eisenstein and Walt Disney, 1930

Paramount had a lot at stake in its deal with Eisenstein, and the company's public relations department promptly started promoting him in Hollywood. Photographs of the Soviet director with American movie stars began to make their way into the press, and the newspapers were full of glowing articles about his filmography.

Simultaneously, however, comments of the opposite tenor began to appear. A certain Major Frank Pease distributed a brochure titled “Eisenstein, Hollywood's Messenger from Hell”. He initially sent it to Paramount’s offices, but then, without waiting for a considered reply from the film studio, circulated it to the editorial offices of major newspapers. In his brochure, Pease cast every possible slur on Eisenstein, describing the director as a dangerous cosmopolitan Jew and accusing him of all the crimes committed by the Bolsheviks after the Revolution.

Pease believed that Eisenstein was a Soviet agent sent to the U.S. to brainwash American citizens: "If your Jewish clergy and scholars haven't enough courage to tell you, and you yourself haven't enough brains to know better, or enough loyalty toward this land which has given you more than you ever had in history to prevent your importing a cut-throat red dog like Eisenstein, then let me inform you that we are bending every effort to have him deported. We want no more red propaganda in this country. What are you trying to do, turn American cinema into a communist cesspool?"

Sergei Eisenstein, Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich

Sergei Eisenstein, Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich

Despite the fact that the text of the brochure raised doubts about Major Pease's mental health, “Eisenstein, Hollywood's Messenger from Hell” still managed to cause a stir in American society. Commenting on Eisenstein's activities in Hollywood, a journalist at the Los Angeles Times wrote: "Paramount could have found a different director and not imported from Russia someone who made propaganda films on orders from the Russian government."

At a high society dinner at the house of the millionaire King C. Gillette, one of the female guests asked the Russian director why he had not prevented the execution of the Tsarist family. Eisenstein sensed that many Americans had started to treat him with suspicion, at the very least.

During his half a year in America, Eisenstein had scripted the films “The Glass House", “Sutter's Gold” and “An American Tragedy”. Paramount turned down the first two on the grounds of their anti-capitalist subtext, but the studio thought the third was highly promising. Even the author of the original novel, Theodore Dreiser, had words of praise for the Soviet director's project. Eisenstein planned to pioneer the device of the internal monologue and to convey the main protagonist's inner world on the screen.

Sergei Eisenstein at work

Sergei Eisenstein at work

In autumn 1930, however, a wave of anti-Soviet sentiment swept the U.S. Congressman Hamilton Fish, a fierce anti-Communist, began an investigation into "Communist activities" in Hollywood, and Eisenstein was included in his hit list. When the Soviet director turned up at Paramount's offices, he was informed that none of his screenplays would be made into a film. The company announced the imminent termination of his contract and agreed to pay for three tickets back to Moscow.

More than a year had passed since Eisensteain had set out on his international trip, and he hadn't yet shot a single full-length movie. But he did not lose hope. Not long before his departure from America, the Soviet director met the writer and left-wing political activist Upton Sinclair, who agreed to finance Eisenstein's new project - an epic with the working title “Mexican Film”. And so, in December 1930, the group of Soviet filmmakers left for Mexico.

Que viva México!

Sergei Eisenstein holding a skull prop

Sergei Eisenstein holding a skull prop

The Mexican Film Trust that Sinclair established specially for the shooting of Eisenstein's movie anticipated that the director would rapidly make a small film showing Mexican customs and exotic landscapes along the lines of a tourist brochure. However, from the very beginning things failed to go according to plan.

In March 1929, the Mexican government had outlawed the Communist Party and also banned Communists from entering the country. Two weeks after their arrival in Mexico, Eisenstein, Aleksandrov and Tisse were detained for questioning. They were bailed out by Mary Craig Sinclair, Upton Sinclair's wife. She organized a campaign to get Eisenstein freed, enlisting the support of Charlie Chaplin, Albert Einstein, Douglas Fairbanks, George Bernard Shaw and two U.S. senators. On receiving a series of telegrams from influential people, the police decided to release Einstein's group and the Soviet filmmakers were declared honored guests of Mexico.

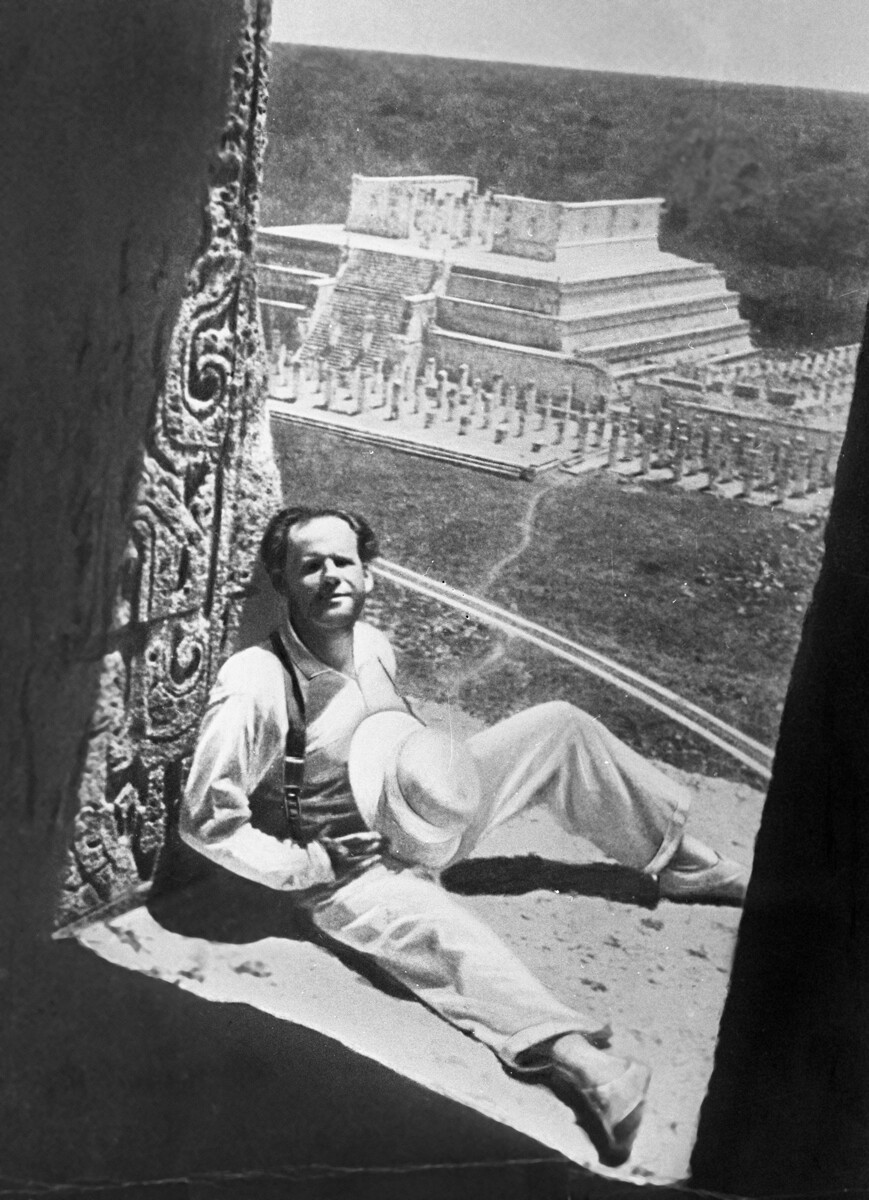

Eisenstein in the Yucatán Peninsula, 1931

Eisenstein in the Yucatán Peninsula, 1931

In Mexico, Eisenstein spent a lot of time with Diego Rivera, whom he had met in Moscow in 1928. The artist introduced his guest to his wife Frida Kahlo and also to Roberto Montenegro and Jean Charlot. The Soviet film director fell under the strong spell of Mexican culture, and realized he wanted to make something bigger than just a pretty but superficial film for tourists.

He shot scenes of bullfights and fiestas in Puebla and Guadalupe, and visited Taxco and Acapulco. In the Yucatán Peninsula he immersed himself in the history of the Maya civilization, committing to film the mighty culture of pre-colonial Mexico. On the Pacific seaboard, in Tehuantepec, he was captivated by the tropical landscapes and observed the customs of the local matriarchal society.

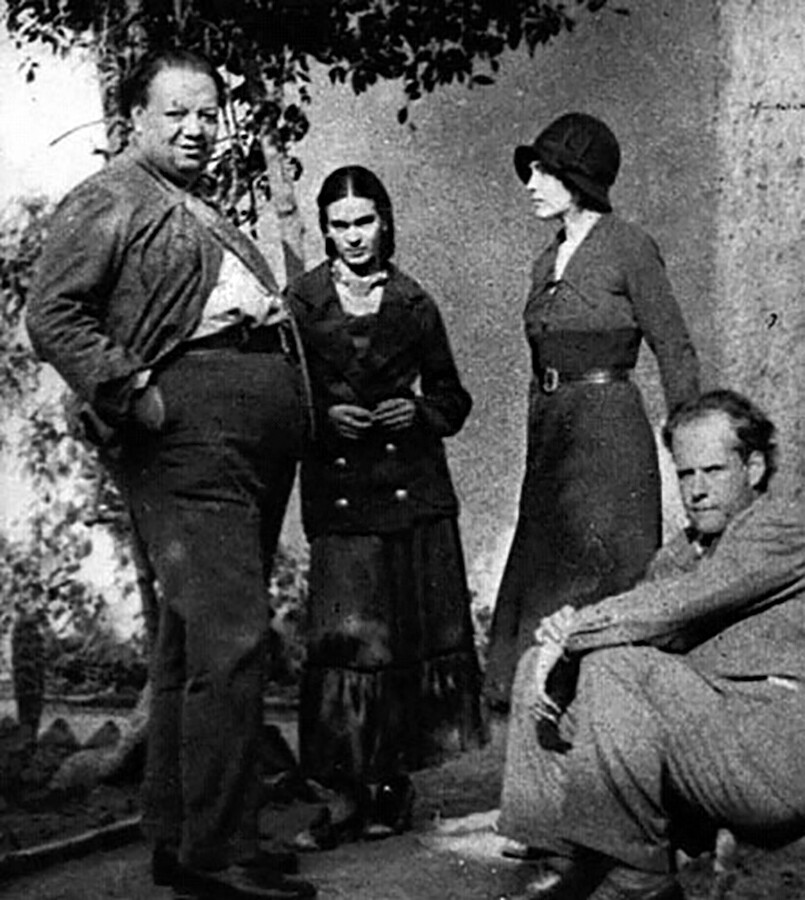

Eisenstein visiting Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo

Eisenstein visiting Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo

Eisenstein significantly widened the film’s scope and changed its title to “¡Que viva México!” The plotline was split into a number of stories embracing several historical eras. But Eisenstein's Napoleonic plans did not come as welcome news to Sinclair - filming was dragging on and the budget was mushrooming. In September, Eisenstein's sponsor was demanding that he set a definitive date for ending work on the film. In addition, Sinclair wrote a telegram to Moscow asking the Soviet leadership to partly reimburse the money he had spent on the movie.

Still from the film ¡Que viva México!

Still from the film ¡Que viva México!

Eisenstein's relations with the Soviet government had also soured by then. In summer 1931, Boris Shumyatsky, the head of Soyuzkino, strongly advised him to return home, but the film director ignored the telegram. It soon became clear that his decision had been a mistake. In November, Sinclair received a communication from Stalin himself (in English) with the following content: "Eisenstein loose [sic - has lost] his comrades' confidence in the Soviet Union. He is thought to be a deserter who broke off with his own country. Am afraid the people here will have no interest in him soon. Am very sorry but all assert it is the fact. Wish you well and to fulfill your plan of coming to see us. My regards, Stalin."

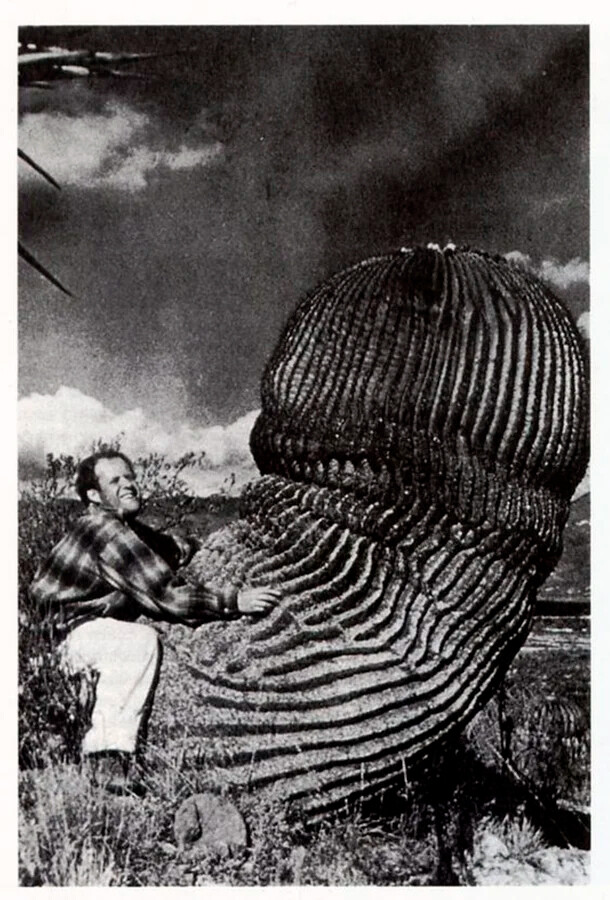

Eisenstein and cactus

Eisenstein and cactus

In early 1932, Sinclair shut down all financing for the film. And so it was that Eisenstein never completed his Mexican epic, handing over 80,000 meters of filmed material to his sponsor. The director hoped that the Soviet government would buy the footage from Sinclair, allowing him to carry out the editing in Moscow, but this was not to be.

Hollywood studios subsequently used Eisenstein's Mexican footage in a number of films (“Thunder over Mexico”, “Viva Villa!”, “Death Day” and “Time in the Sun”), but all significantly distorted the filmmaker's intentions. In the Soviet Union, “¡Que viva México!” was released after Stalin's death and only in 1979. The film was edited by the then-elderly Grigori Aleksandrov, who sought to approximate this version as closely as possible to his mentor's original concept.

Eisenstein returns to the USSR. Left: the director's mother

Eisenstein returns to the USSR. Left: the director's mother

Eisenstein returned to Moscow in May 1932 to a cool reception. He was only able to restore his reputation six years later when he made the patriotic film “Alexander Nevsky”, but ultimately he never became a fully ideologically compliant filmmaker.

In 1946, Stalin took great exception to the ideological subtext of “Ivan the Terrible, Part II'”. Eisenstein was banned from shooting anything else until the film was revised. He took his estrangement from cinema with great anguish, and this had an effect on his health. Sergei Eisenstein died of a heart attack in 1948, aged 50. Remaining true to his ideas, however, had made him one of the greatest film directors in history, but it was also his undoing.