Why Leo Tolstoy was an anarchist

Leo Tolstoy can, indeed, with some reservations, be called an anarchist. He didn’t recognize or fear any authority. The great writer openly denounced the Russian authorities and the church. His followers were arrested and exiled, while his books and articles were banned (‘The Kreutzer Sonata’, ‘Christianity and Patriotism’, ‘What I Believe’ and others). But, no-one dared touch the author himself. Only at the end of his life was he excommunicated, but even that was somewhat half-hearted - no anathema was proclaimed against him in any church. Incidentally, he also had protection in high places: For example, the writer’s aunt, Alexandra, was lady-in-waiting to Empress Maria Feodorovna, consort of Alexander III.

Against all violence

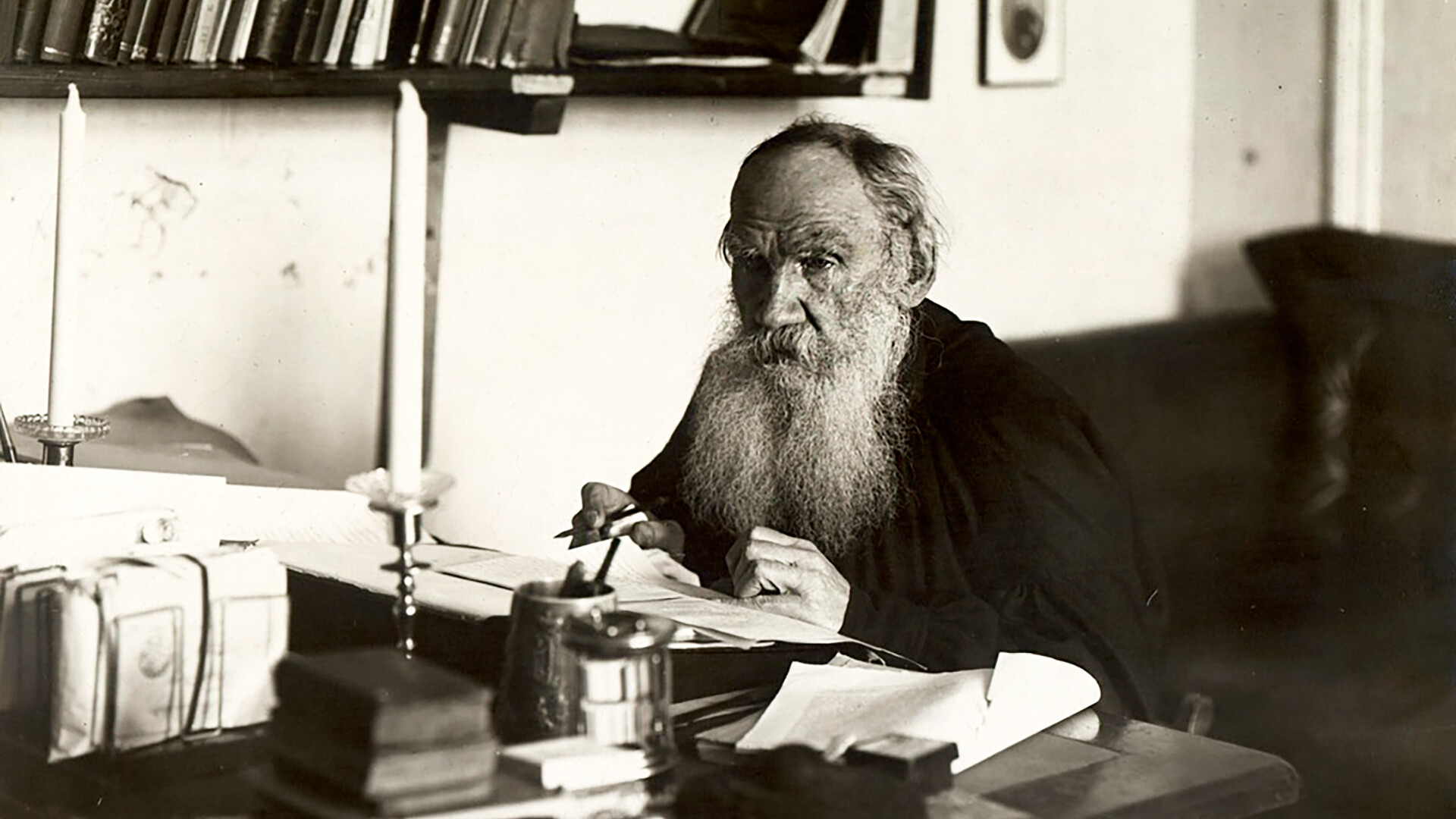

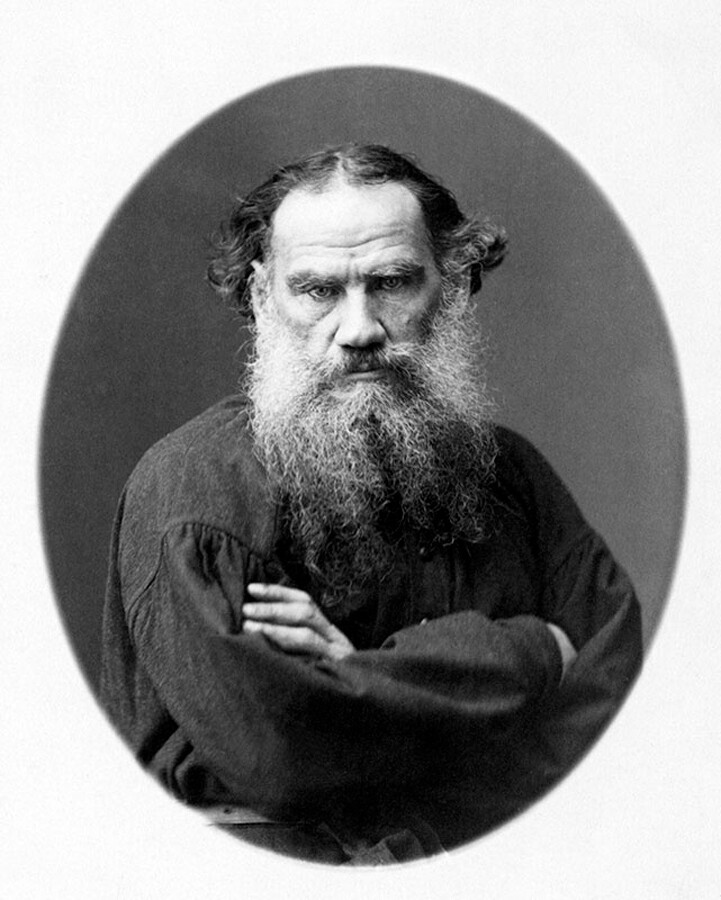

Leo Tolstoy in 1885

Leo Tolstoy in 1885

Throughout his long life, Tolstoy redefined the problems of human authority and state power and how the two relate to morality several times. He denounced all violence and one of the main principles of his late philosophy was “non-violent resistance to evil”. In this sense, he was close to the Eastern philosophers and to Taoism. This principle of his also inspired Mahatma Gandhi, with whom Tolstoy even corresponded. It was from Tolstoy that Gandhi said he got his idea of “satyagraha” - nonviolent civil disobedience, or “passive resistance”.

Tolstoy had a low opinion of Russian authorities, but he didn’t see Western states in the best light, either. The entire history of Europe, according to Tolstoy, is a history of stupid and reprobate rulers “killing, despoiling and, most importantly, corrupting their people”. The same thing is repeated whoever ascended the throne - death and violence against people. And this happened even in all “supposedly free constitutional states and republics”.

If rulers had been virtuous and highly moral individuals, then the subordination of a whole people to them could have been justified. In Tolstoy’s view, however, those in charge are always the most “wicked, worthless, ruthless, immoral and, most crucially, deceitful people”. It was as if all these qualities were a necessary qualification for power.

In his article ‘The One Thing Needed. Concerning State Power’, Tolstoy lumped together the “debauched Henry VIII”, the “malefactor Cromwell” and the “hypocrite Charles I”… Tolstoy was also very rude about Russian tsars, branding Ivan the Terrible as “mentally ill”, Catherine the Great as a “German woman of shamelessly wanton conduct” and Nicholas II, to take another example, as a “hussar officer of limited intellect”.

The state as pure evil

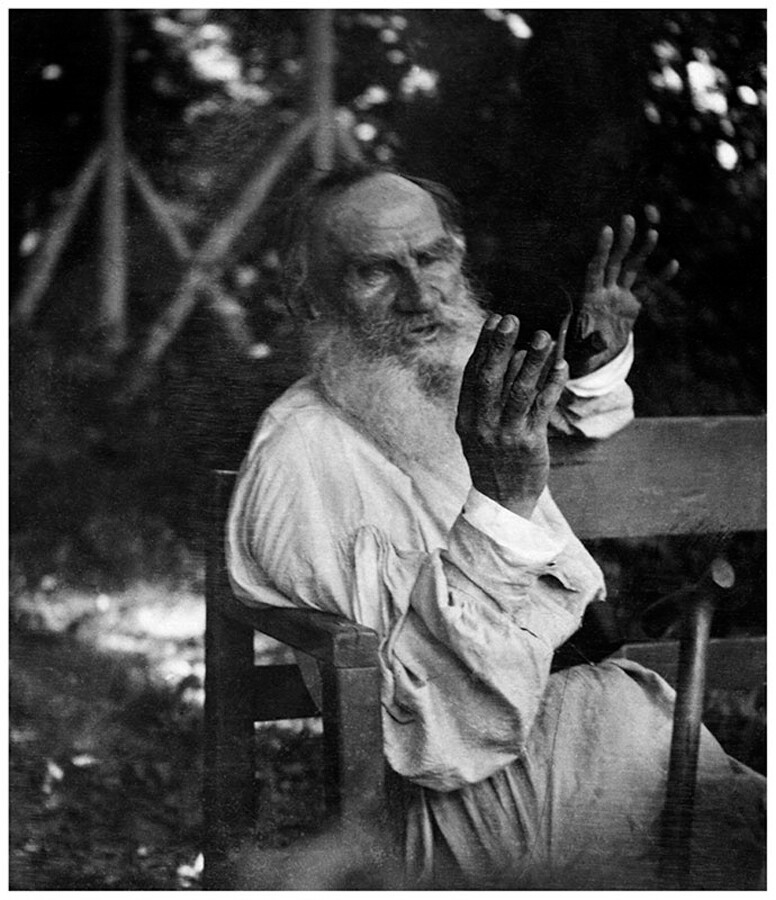

Leo Tolstoy in 1903

Leo Tolstoy in 1903

Tolstoy viewed the entire history of the European Christian nations since the Reformation as a “ceaseless inventory of the most terrible, senselessly violent crimes committed by government officials against their own and other peoples and against one another”.

Tolstoy saw the state as a thief that took away from people born on their own land the right to use said land. People were even forced to pay for the right to be on the land - they were compelled to render tribute in labor or money merely to be able to live. The state defended this theft as its sacred right.

Violence is committed against a child from its very birth when it was baptized in the established religion or sent to school where it was taught that the government of his country is the best there is - no matter “whether it is the government of the Russian tsar, or the Turkish sultan or the British government with its [Joseph] Chamberlain and colonial policy or the government of the North American States with its patronage of corporate trusts and its imperialism”.

And so Tolstoy concluded: “The activities of any government are a succession of crimes.”

The answer - a rejection of all authority

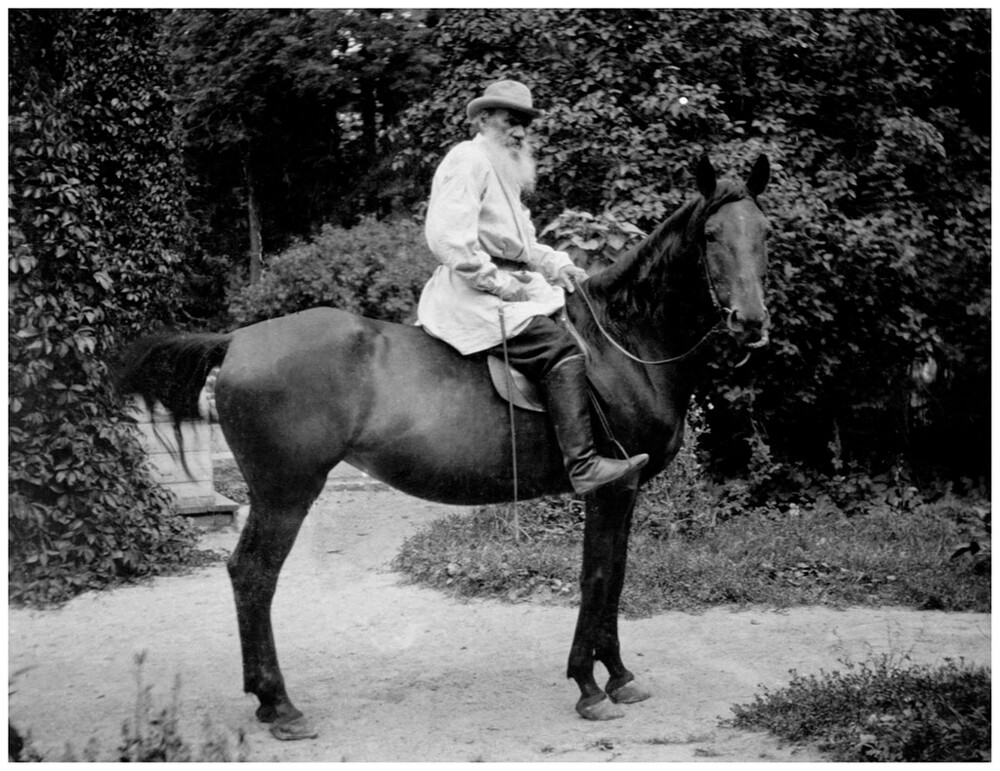

Tolstoy riding his favorite horse, Zorka, 1903

Tolstoy riding his favorite horse, Zorka, 1903

A person guided in life by the ideals of reason and virtue should logically renounce all violence and stop supporting it. But people merely give violence new forms. “It’s like a man carrying a useless load <…> who shifts it from his back to his shoulders, from his shoulders to his thighs and then onto his back again, without having the sense to do the one thing necessary - to discard it.”

Thus, Tolstoy believed that all state systems should simply disappear. But, how would order be maintained then? The writer saw the answer in religion, in moral values, in faith (whether it be a belief in Christ or the Buddha) and in humanitarianism. In his view, if people were going to be moral, there would be no need to apply against them the force that is commonly exercised by any state system.

“European nations moved from a lower to a higher state when they adopted Christianity; just as the Arabs and Turks moved to a higher stage of development when they became Mohammedans and the nations of Asia when they adopted Buddhism, Confucianism or Taoism,” he wrote.

At the same time, Tolstoy was perfectly aware that this is impossible now - and he explained why. The reason, as he saw it, was that religion had been weakened among the nations of the Christian world, “if it is not absent altogether”, and, yet, it is the principal driving force of any nation.

In addition, contemporary Christian faith also seemed bogus to Tolstoy. It had absorbed all sorts of “nonsenses” in the course of over a millennium and no longer provided any fundamental principles of behavior, “apart from blind faith and obedience to the persons who called themselves the church”. The present-day institution of the church filled the place that should have been occupied by a true religion that gave people an explanation of the meaning of life.