How Russian ballerinas taught Europe to dance

To dance in a professional troupe in the early 20th century one needed to have a Russian last name; and to study ballet one needed to take classes from a ballerina of the Russian Imperial Theaters. The 1917 Russian Revolution thrusted most of those ballet professionals out of the bright, spacious halls on Theater Street in St. Petersburg and into the studios of Paris, Nice, London, Berlin, New York, and Shanghai.

“I have to say that I owe my education as a dancer to Russian teachers, the soloists of the Imperial Theaters who taught in Paris,” legendary French dancer and choreographer Maurice Béjart remembered later in life. “By the time of my arrival in Paris there existed a whole colony of Russian teachers that’s hard to describe now. This was a world that’s no more. It seemed as though all of them had come right out of some short story by Chekhov or Gogol.”

Here’s the story of the ballerinas who taught the world how to dance in the 20th century.

Olga Preobrazhenskaya

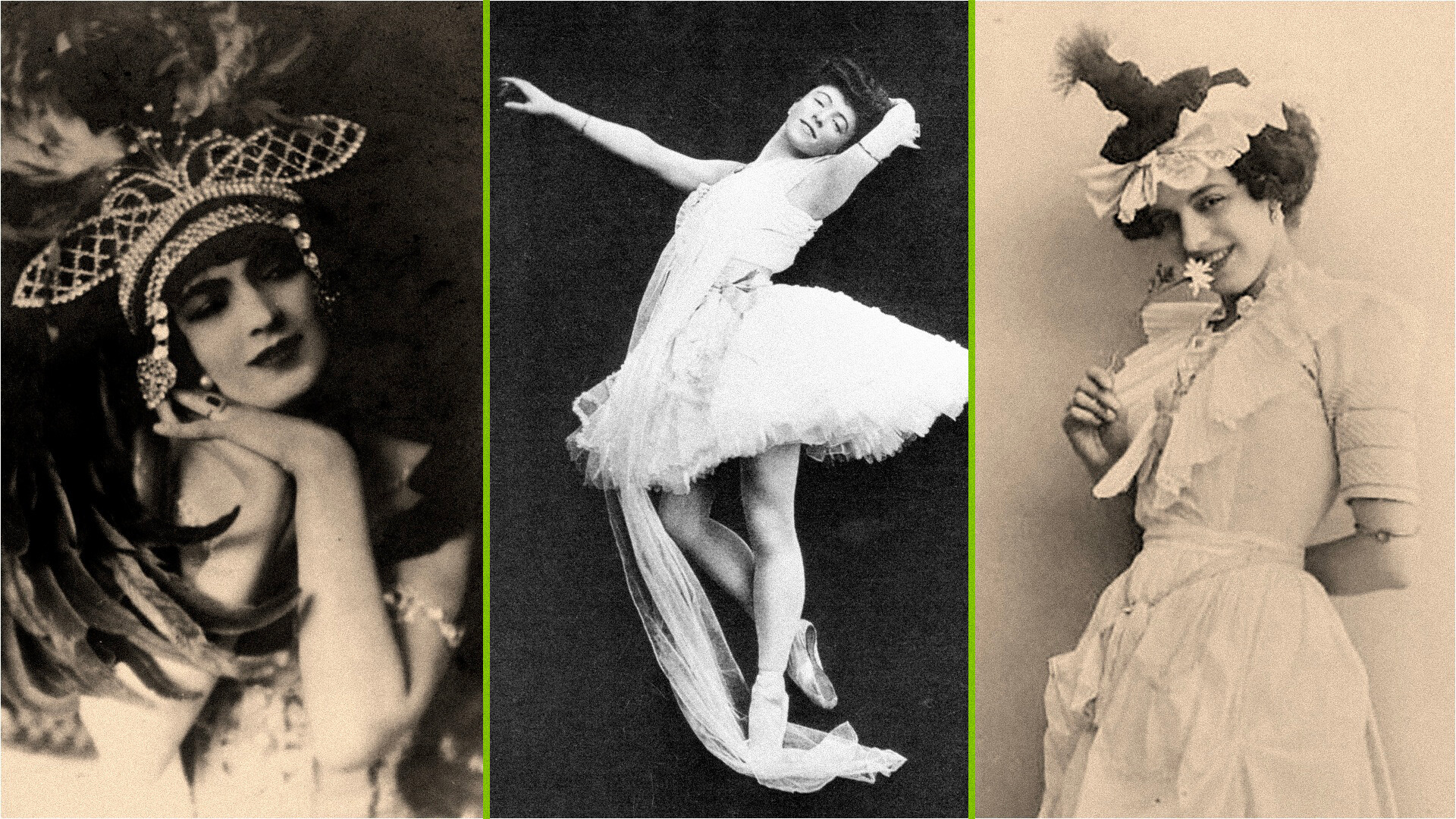

Ballerina Olga Preobrazhenskaya in a scene from Cesare Pugni's ballet 'The Little Humpbacked Horse'.

Ballerina Olga Preobrazhenskaya in a scene from Cesare Pugni's ballet 'The Little Humpbacked Horse'.

Unlike the majority of her colleagues, Olga Preobrazhenskaya started to teach long before her emigration. A favorite of the famous French-Russian choreographer Marius Petipa, she had an uncanny ability to enhance the music and elevated the ballet music composer Cesare Pugni to the level of Pyotr Tchaikovsky. She was not distinguished for her physical features, yet she possessed an analytical mindset. She reflected on other teachers' classes and systems, trying to take the best of them, and used this knowledge to eventually improve her own teaching practice.

Then Agrippina Vaganova and Lyubov Yegorova (and later Olga Spessivtseva) asked for her help to prepare new ballet roles. After the Revolution, Preobrazhenskaya began to teach at a local St. Petersburg ballet school. Her creative search in dance led to a synthesis of assertive Italian virtuosity, French finesse, and Russian music ability that formed the expressive modern Russian style of ballet that later received its final shape in Vaganova’s methodology.

Preobrazhenskaya left Russia in 1921, and she earned a living giving ballet lessons in Buenos Aires, London, Milan, and Berlin, until finally settling in Paris. “Despite the shouting that accompanied her classes, it was clear that Olga and her students respected each other,” remembered ballerina Nina Tikhonova, who herself was the daughter of Russian emigrants. “That’s why the latter, often dumbfounded by her anger, never took offense. She didn’t have even a hint of vulgarity, and her irony was never insulting. I suspect that she shouted with the goal to draw forth the maximum intensity from her students. In ballet, you have to know how to handle your nerves and how not to lose your head.”

Her studio on the Boulevard des Capucines became one of the main centers of gravity for Europe’s ballet scene. Not every ballet academy could boast such a list of students. Among them were Irina Baronova, Margot Fonteyn, Igor Youskevitch, George Skibine, Milorad Mišković, Nadia Nerina, André Eglevsky, Pierre Lacotte, as well as several generations of entertainers who defined the modern world of ballet.

Lyubov Yegorova

Lyubov Yegorova dressed for 'The Blue Dahlia' ballet (choreography by Marius Petipa and music by Cesare Pugni)

Lyubov Yegorova dressed for 'The Blue Dahlia' ballet (choreography by Marius Petipa and music by Cesare Pugni)

“I learned from a fantastic woman – Lyubov Yegorova. She was like a mother to me and she did a lot to form my culture. When I came to Russia for the staging of The Pharaoh's Daughter and went to the Theater Museum in St. Petersburg to find documents about the history of this ballet, the first folder I opened held the photo of Yegorova on top in her favorite role of Aspicia. For me, that was symbolic. She was there to protect me,” French dancer and choreographer Pierre Lacotte remembered.

At the same time as Lacotte, Maurice Béjart also took lessons from Yegorova. The war was raging, and it was freezing in his Paris studio. When it proved impossible to continue practicing, Yegorova, who married Prince Nikita Trubetskoy in emigration, called out to her husband: “Prince, bring some coal!”

Béjart barely had any money to pay for the lessons. Many years later the master recalled how Yegorova scheduled pair lessons for him with some students who had little talent.

“She pays, you work!” the kind-hearted Yegorova commanded categorically, giving the wealthy student ten minutes of her time and the other fifty minutes to the talented one – Béjart.

Among visitors to her Paris studio, which opened in 1923, were Roland Petit, Serge Lifar, Zelda Fitzgerald, Rosella Hightower, and many others.

Serafina Astafieva

Serafina Astafieva, 1890s

Serafina Astafieva, 1890s

A tall dancer with a spectacular appearance, Serafina Astafieva prided herself on a close kinship with writer Leo Tolstoy. She was unable to attain the title of a ballerina of the Imperial Theaters, and didn’t have ambitious career plans. She married very young, gave birth to a child, and was content with supporting roles on stage. But she stood out in these minor roles and was invited by Sergei Diaghilev to join his first Ballets Russes in Paris. In London she enjoyed massive success, where she replaced Ida Rubinstein as Cleopatra.

With this good fortune, Astafieva decided to stay in London, where, undaunted by competition from Anna Pavlova, she opened her own ballet school in Chelsea. A student of Yekaterina Vazem, one of the favorite ballerinas of Petipa, Astafieva utilized her pedagogical techniques. For over 20 years she gifted English ballet its first and its brightest stars: Anton Dolin, Alicia Markova, and Margot Fonteyn.

Vera Volkova

Teacher Vera Volkova (at right) shows Billy Marlin-Viscount and Linda diBona a lift from Assaf Messerer's 'Spring Waters', 1965

Teacher Vera Volkova (at right) shows Billy Marlin-Viscount and Linda diBona a lift from Assaf Messerer's 'Spring Waters', 1965

Not only did Vera Volkova miss her chance to become a ballerina of the Imperial Theaters, she wasn’t even able to enroll in a drama school. But this is through no fault of her own. Her childhood coincided with the years of revolution in Russia. When she decided to study ballet, it was already too late to enroll in a drama school.

At this time, however, the School of the Baltic Fleet, also known as the School of Russian Ballet of Akim Volynsky, had opened in St. Petersburg for those who were older than the usual required age for study. The pedagogical careers of many teachers began here, such as Olga Preobrazhenskaya, Maria Romanova, the mother of Galina Ulanova, as well as Agrippina Vaganova, one of the first students of which Volkova became.

Despite the accelerated study, she learned the methodology of classic dance from her young teacher. Volkova never had the opportunity to become an outstanding dancer because her fate was so turbulent, constantly forcing her to move to different places: Japan, Moscow, Shanghai and Hong Kong. Though having waved good-bye to the big stage, Volkova didn’t lose her passion for dancing. In 1936 she found herself in Europe, and visited the Paris ballet studios of Yegorova, Knyazev, and Spessivtseva.

The start of World War II forced her to settle in London where she resumed classes with her Shanghai student Peggy Hookham and Margot Fonteyn, who had already managed to become a rising star of the English ballet. This cooperation, spanning many years, turned out to be crucial for both: during lessons Fonteyn found her style, while Volkova became a household name.

She was invited to head the ballet at Milan’s La Scala and then at the renowned Royal Danish Ballet in Copenhagen. Volkova began to modify Bournonville’s heritage in Copenhagen, first of all by putting his La Sylphide’s corps de ballet in pointe shoes. Her eye demanded flawless academism, but yet at the same time she helped to shape modern dance forms – dynamic, mobile, and sharp.

That’s why the cream of the crop of the ballet world would go to Denmark; these included Zizi Jeanmaire and Roland Petit of France; Svetlana Beriosova of Britain, Melissa Hayden of the U.S.; as well as Soviet defector Rudolf Nureyev, and Carla Fracci of Italy.