9 unusual coins from tsarist times (PHOTOS)

1. Square ruble

Copper ruble, 1725

Copper ruble, 1725

Coin minting doesn’t come cheap. Peter the Great learned that from experience. Under his rule, instead of the usual elongated coins that were typical of medieval Russia, it was decreed to make round coins just like in Europe. While there wasn’t enough silver there was an abundance of copper in the Ural region. A reform of the coinage took place under Peter’s wife and heir, Catherine I. In 1726-1727 the mining operations near Yekaterinburg produced branded ingots. They weren’t pretty: each had a square with the Russian coat of arms in four corners and a number for the denomination, and in its center was stated the place where and when the coin was minted. In that manner, coins from the smallest, such as one kopeck, to the largest, such as one ruble, were minted. The bigger the coin, the heavier it got. For example, a kopeck weighed slightly over 16 grams, while a copper ruble was the size of a hand and weighed more than 1.6 kilograms!

2. Sestroretsk ruble

You could hammer nails with a Sestroretsk ruble – the giant coin weighed 930 grams. The usual pyatak (5 kopecks) weighed 50 grams at the time. Looking like a miniature hockey puck, this copper ruble was exchangeable for the first Russian paper money – assignats. At least that was the idea when in 1771 the Sestroretsk military works began minting test batches. But this plan didn’t go any further – these coins never went into circulation.

3. Platinum coins

Platinum 3-rubles coin (1828)

Platinum 3-rubles coin (1828)

Just several years after platinum began to be mined in Siberia, a decision was made to mint money made with the precious metal. Three-, six- and 12-ruble coins were the first in the world made from this metal. They were minted for less than 20 years, from 1828 to 1845. During that time, half of the mined 32,000 kilograms of platinum were turned into money. It seemed that this very precious coin would occupy an esteemed place next to its silver and golden brethren, but then everything suddenly stopped. According to one version, this happened because of fears that this precious metal was about to depreciate. All of the existing platinum reserves were sold to England, and money like that was never again minted.

4. Half measures

A gold 37.5-ruble coin (1902)

A gold 37.5-ruble coin (1902)

Under Russia’s last emperor a currency reform was carried out, and the value of the ruble was tied to gold. In addition to coins of the usual denomination, a non-standard one also entered into circulation, namely a 7.5-ruble coin. But the mint also had to produce money with a much higher value. For example, the gold 37.5-ruble coin. The round coin of 1902 with Nicholas II’s profile and the Russian coat of arms had two values at once – the ruble and the French franc – because it was intended for overseas payment. It’s likely that this coin made of .900 gold was needed for ceremonial gifts – members of the Imperial family became the main owners of this unusual coinage.

5. 'Rus' instead of ruble

5 'rus' was 1/3 of the imperial gold coin (1895)

5 'rus' was 1/3 of the imperial gold coin (1895)

Imperial Russia’s greatest finance minister, Sergei Witte, decided to reinvent the gold ruble and increase its value on the global market. From among several name options he chose the Frenchified rus. Visually, the new money differed little from the old, and the new denomination remained the same. For example, the gold imperial (15 rubles) turned into 15 ruses; while 2/3 of the imperial gold coin – a 10-ruble coin – was worth 10 ruses. Nicholas II, after having acquainted himself with the new mint, remained indifferent to Witte’s idea. The old ruble was left in circulation, while the proposed currency never got beyond the project stage.

6. Siberian money

5-kopeck coin (1772)

5-kopeck coin (1772)

With the conquest and development of new territories a serious problem arose: it was quite expensive to deliver money minted in St. Petersburg to the remote corners of Russia. Hence, it was decided to mint some coins locally. For Siberia, starting in 1766, money was made at the Suzunsky mint (just south of Novosibirsk) from the nearby rich copper reserves. However, the money only circulated locally, from Tara to Kamchatka. Almost all of the coins, aside from the smallest denomination – polushka – featured the coat of arms of the Tsardom of Siberia on their reverse.

7. A coin without a portrait

1-ruble coin of Paul I (1789)

1-ruble coin of Paul I (1789)

Paul I had a simple solution for Russia’s formidable foreign debt and growing inflation: he destroyed the assignat reserves and increased the amount of metallic currency. All sorts of methods of raw material production were utilized, and even palace silver tea sets were melted down. Under Paul’s rule, for the first time, coins were minted without the tsar’s portrait – it was replaced with a monogram that had four “П”s (P in English) and the Roman “I” in the middle. The coin’s reverse featured words from the Book of Psalms, “Not unto us, not unto us, but unto thy name.” By the way, not only regular poltinas and rubles looked like this, but also experimental coins known as efimoks. These silver coins were equal to 1.5 rubles.

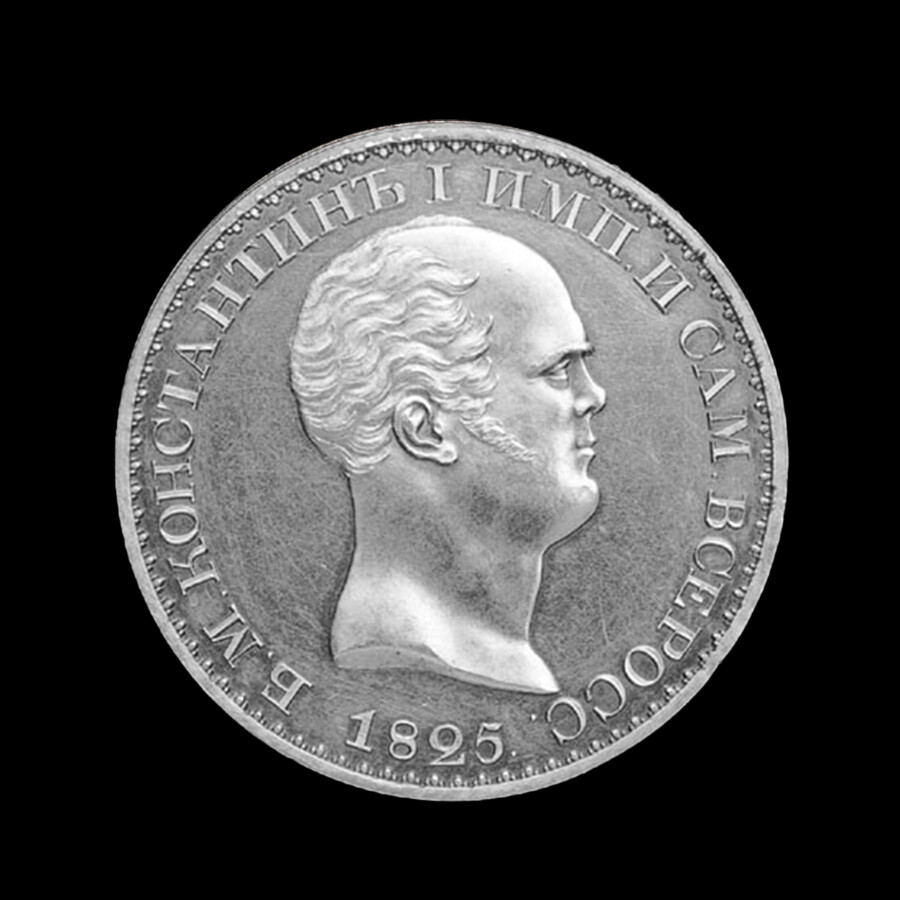

8. Konstantin ruble

Konstantin ruble (1825). Stamp based on Reichel's drawing

Konstantin ruble (1825). Stamp based on Reichel's drawing

Strange: a monarch named Konstantin never sat on the throne in Russia, but there were coins with his portrait. It’s in fact very simple. After the death of Alexander I, who had no children, Konstantin, the son of Paul I, should have ascended to the throne. But he refused to become emperor, and so it was decided to hand the throne to his brother, Grand Duke Nicholas. Several years before his death, Alexander I drew up a secret document in which he confirmed Nicholas’ rights to rule. But not everyone knew about this manifesto. That’s why the St. Petersburg Mint started making new money without waiting for his coronation. In the end, almost the entire batch was destroyed aside from a few coins.

9. A gold coin instead of a medal

Gold Medallion with the image of Princess Sophia Alexeyevna (1682-1689)

Gold Medallion with the image of Princess Sophia Alexeyevna (1682-1689)

The saying that gold is the “metal of kings” is 100% true. After their coronation, monarchs were often showered with precious coins, and used for decoration and as gifts. Gold coins were also awarded for military achievements. Only in the 18th century were they replaced with medals and orders. For example, Fyodor Golovin, who signed the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689 that established the borders between Russia and China, was awarded with a gold coin.