8 little-known facts about the Nuremberg trials of Nazi leaders

In addition to the accused and their lawyers, judges and prosecutors from the four victorious Allied powers - the USSR, France, Britain and the United States - participated in the proceedings in Courtroom 600 at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Germany. During almost a year of proceedings, various events and incidents took place at the trials. Some are common knowledge today, but others are less well known.

1. The HQ of the International Military Tribunal was in Berlin, not Nuremberg

Headquarters of the Allied Control Council in Berlin

Headquarters of the Allied Control Council in Berlin

The Soviet leadership insisted that the trial be held in Berlin where the victorious powers had established the Allied Control Council - the supreme administrative authority of the victors on the territory of defeated Germany.

But the Western Allies insisted on Nuremberg in the American occupation zone. The Palace of Justice had survived intact there and it was connected through an underground passage to a prison, something that Berlin didn't have. The venue was also considered symbolic - it was here that all the congresses of the National Socialist Party of Germany had been held since 1927.

Nevertheless, in the end Berlin was chosen as the location of the headquarters of the International Military Tribunal, and there in early October 1945 several organizational meetings were held in the building of the Allied Control Council. The first court sitting of the tribunal was held at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg on November 20, 1945.

2. Seven defendants managed to avoid punishment

Hitler is pictured flanked by Field Marshal Keitel, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring and Martin Bormann. The photographer is unknown

Hitler is pictured flanked by Field Marshal Keitel, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring and Martin Bormann. The photographer is unknown

Indictments were brought against 24 of the most notorious Nazi criminals. Twelve defendants were sentenced to death, but two managed to avoid execution.

The fate of these following seven top Nazis is noteworthy because some were acquitted or the official punishment was never carried out.

Hermann Göring, the supreme SA leader, general of SS troops, Reich Minister of Aviation and Hitler's designated successor, was sentenced to death. Before his execution, however, he killed himself by ingesting cyanide, thus escaping the gallows.

Hermann Göring during cross examination at his trial for war crimes, 1946

Hermann Göring during cross examination at his trial for war crimes, 1946

Martin Bormann, head of the Nazi Party Chancellery and the Führer's private secretary, was sentenced in absentia to death since he was not present at the trial - his whereabouts were unknown. In early May 1945, Bormann was allegedly killed during a Soviet bombardment of Berlin. However, his body was never found. In 1972, remains allegedly belonging to Bormann were found, but only in 1998 did a DNA test finally proved their authenticity.

Robert Ley, chairman of the German Labor Front, hanged himself in his prison cell before the start of the trial on October 25, 1945, a few days after receiving the indictment.

Gustav Krupp von Bohlen, head of the Krupp industrial conglomerate that financed and built the Nazi war machine, was declared terminally ill. During a preliminary hearing on November 15, 1945, before the trial even began, the case against the entrepreneur was suspended.

Three other defendants were acquitted - Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen; Hans Fritzsche, head of the Radio Division of the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda; and Hjalmar Schacht, Reich Minister of Economics.

3. People sat in the courtroom wearing sunglasses

Hermann Göring (left) and Rudolf Hess (right) during the war criminal trials at Nuremberg, September 30, 1946

Hermann Göring (left) and Rudolf Hess (right) during the war criminal trials at Nuremberg, September 30, 1946

Photographs and archive video from the tribunal show some participants wearing sunglasses. The reason was the lighting in the courtroom. This is how Boris Polevoy, special correspondent of Pravda newspaper at the tribunal, described the lighting in his book "The Final Reckoning: Nuremberg Diaries": "A pale, flat, somehow impersonal and oppressive light, in which everything around acquires a greenish, deathly hue." The curtains on all the windows were drawn. According to Polevoy, prison commandant U.S. Colonel Burton Andrus once quipped to reporters: "I will see to it that none of them ever see the sun."

The artificial light gave many people sore eyes, so those present, including the defendants, sometimes wore dark glasses.

4. Journalists were barred from some tribunal sessions

The reporters dash away with the news of the sentences passed at the conclusion of the 'greatest trial in history' at the Palace of Justice, Nuremberg

The reporters dash away with the news of the sentences passed at the conclusion of the 'greatest trial in history' at the Palace of Justice, Nuremberg

The public was barred from closed sessions, as were journalists. When that happened, the following rule was devised to provide some indication as to what was going on in the courtroom, recalled Boris Polevoy. "If something interesting emerged during the proceedings, then a single alarm sounded in all rooms of the Palace of Justice. If something particularly noteworthy was in progress then there was a double signal. And if something sensational occurred the alarm sounded three times."

According to Polevoy, these signals resembled a rather sharp, almost roaring sound, and seemed to come from somewhere just beneath the ceiling. And it repeated over and over again for some seconds.

5. The U.S. press wrote that the Soviet prosecutor had shot Göring

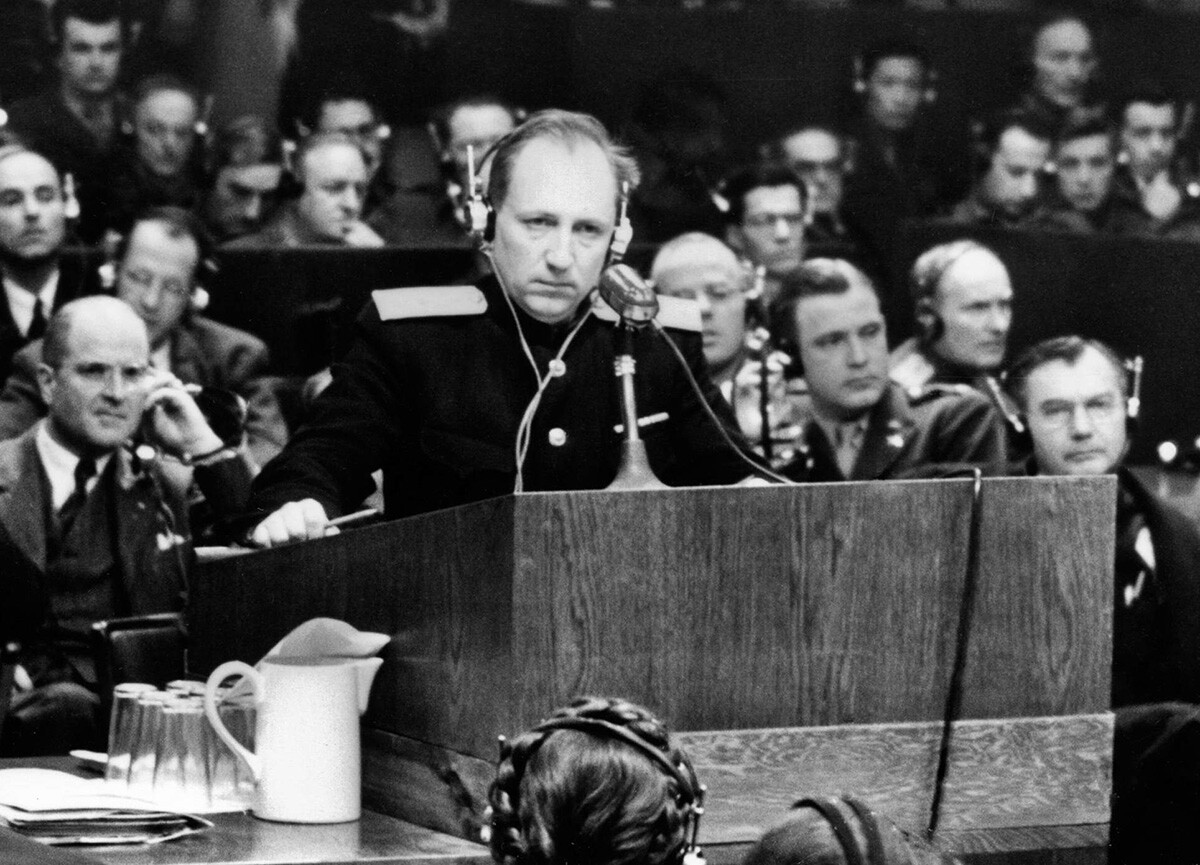

Soviet chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, General Roman Rudenko

Soviet chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, General Roman Rudenko

On April 10, 1946, the U.S. Army newspaper Stars and Stripes published a report saying that Soviet prosecutor Roman Rudenko had become so enraged at Göring at one of the court sessions that he drew his service weapon and shot the former Reichsmarschall.

The newspaper subsequently published a retraction, however. Its clarification went along the following lines: "The report that the Soviet chief prosecutor at the trial shot Göring in a fit of fury has proved not to be the case. According to a correspondent from Nuremberg, Göring is alive and well and willing to answer the prosecutor's questions. The report that he died tragically had been derived from the editorial team's incorrect interpretation of a phrase used by the correspondent, who had reported that General Rudenko had morally gunned down Göring."

6. Göring’s testimony helped Boris Polevoy to write his 'The Story of a Real Man'

Pravda newspaper's war correspondents at the Nuremberg Trials. From left to right: Boris Polevoy, Vsevolod Vishnevsky and Viktor Temin

Pravda newspaper's war correspondents at the Nuremberg Trials. From left to right: Boris Polevoy, Vsevolod Vishnevsky and Viktor Temin

Polevoy started writing his Stalin Prize-winning novel based on the story of fighter pilot Aleksey Maresyev at Nuremberg. He was inspired by the words of Göring, who, when asked whether he regarded the start of the war against the USSR as a supreme crime that plunged Germany into catastrophe, replied:

"It was not a crime, it was a mistake <…> Our intelligence services were operating fairly well, and we knew the approximate size of the Red Army, the number of their tanks and planes, and we knew the capacity of the Russian weapons factories. <...> But we didn't know the Russians. The people of the East have always been an enigma for the West."

7. A Soviet interpreter was the "last woman in Göring’s arms"

Tatiana Stupnikova, Soviet translator who worked at the Nuremberg trials

Tatiana Stupnikova, Soviet translator who worked at the Nuremberg trials

One day during the proceedings, 24-year-old interpreter Tatiana Stupnikova was hurrying to her place in the courtroom. While she was running along the corridor, she accidentally slipped and almost fell.

"When I regained my composure and looked up at my rescuer, I was confronted by Hermann Göring’s smiling face just beside me. He managed to whisper in my ear: ‘Vorsicht, mein Kind!’ (‘Be careful, my child!’),” Stupnikova recounted in her memoirs.

When Tatiana entered the courtroom, a French correspondent came up to her and said to her in German: “You were the last woman Göring will hold in his arms.” Read more about this story in our article.

8. A Wehrmacht field marshal was a witness for the Soviet prosecution

Friedrich Paulus at the Nuremberg Trial

Friedrich Paulus at the Nuremberg Trial

By the autumn of 1946 the court proceedings were bogged down. Claims started to be heard from the defense, and the accused themselves, that Nazi Germany's attack on the USSR had been a pre-emptive measure. The Soviet delegation needed to provide compelling arguments that the attack by the Third Reich had been planned well in advance.

The "trump card" that was unexpectedly produced came in the person of Friedrich Paulus, who had been taken prisoner at Stalingrad on January 31, 1943. The Soviet leadership secretly brought Paulus to the Palace of Justice to testify. During cross-examination at Nuremberg, the former German marshal declared that "all the preparations for the attack on the USSR that took place on June 22 had in fact already been in progress in autumn 1940".

Read more on Friedrich Paulus's role at the Nuremberg Trials and how the former Wehrmacht field marshal lived in the USSR after the war.