Why did Russia & China establish diplomatic relations only after the war?

The first contacts between Russians and Chinese date back to the 13th century. During the invasion of Russia, the Mongols took Russian prisoners to Beijing, where they swore an oath to the emperor of the Mongol Yuan dynasty.

In the fifteenth century, Russian merchants first entered China. In the 16th and 17th centuries, trade was developing intensively; in addition, Russians were actively developing Siberia and the Far East. It would seem that these were the prerequisites for the establishment of official contacts between Russia and China. Nevertheless, the countries only agreed on borders in 1689, after a military conflict.

The Nerchin Treaty of 1689

View of Nerchinsk from "Notes of Ides"

View of Nerchinsk from "Notes of Ides"

In the 1640s, the Russians began to develop the Amur region. The Qing dynasty of Manchuria also claimed these no man’s lands, although it did not control them.

In 1685 and 1686, Qin troops besieged the Russian fortress of Albazin on the Amur River and, in 1689 - another fortress to the west on the Shilka River Nerchinsk. Years of border clashes ended with the signing of the Nerchinsk Treaty. The document, drawn up in Manchurian and Latin (but not in Russian - there were no translators!), for the first time defined the relations and borders between the two states. (Read more)

The same events served as a prologue to the appearance of the Russian spiritual mission in China. In 1685, some of the Cossacks from the Albazin fortress passed into Chinese citizenship. A Buddhist temple was allocated to them for worship. Priest Maksim Leontiev, who moved there with the Cossacks, turned it into an Orthodox chapel. Leontiev’s activity helped establish Russian missionary activity in China at the beginning of the 18th century.

Why didn’t China develop diplomatic relations on its part?

Russian Ambassadors of the 17th Century in China (Niva magazine)

Russian Ambassadors of the 17th Century in China (Niva magazine)

Until the middle of the 19th century, Russia sent 18 embassies of different levels to the Qing Empire. Russian diplomat Savva Raguzinsky in the late 1720s found information in Beijing archives that after the conclusion of the Nerchinsk Treaty about 50 Russian “envoys” visited the country (many of them acted without the knowledge of the central authorities). And in the 17th-18th centuries, only four Chinese envoys visited Russia and only two of them visited Moscow and St. Petersburg.

The Chinese emperors were simply not interested in developing diplomatic relations with Russia. Many guests stayed in the Chinese “reception room”: some heads of missions could not get to the emperor for months and left with nothing. In the 17th century, the Chinese emperor personally greeted only four Russians.

The Soviet and Russian Chinese scholar and academic Vladimir Myasnikov notes that China’s foreign policy doctrine was based on the thesis of its own superiority and the “barbarity” of other nations. Beijing sought to impose the status of vassal to all countries that came into contact. All Chinese diplomacy and court ceremonials were adapted to this idea. The eastern ruler did not welcome guests without certain procedures; communication with a foreign representative as equals was rather the exception (or a military trick). The further on, the stricter this system worked.

Beijing was interested in establishing dominance primarily in neighboring Asian countries. It viewed trade ties only as a means of achieving its political goals. Unlike Russia, for China, trade was something of a minor importance. Moscow familiarized itself with the peculiarities of the Chinese worldview throughout the 17th century.

A missed opportunity

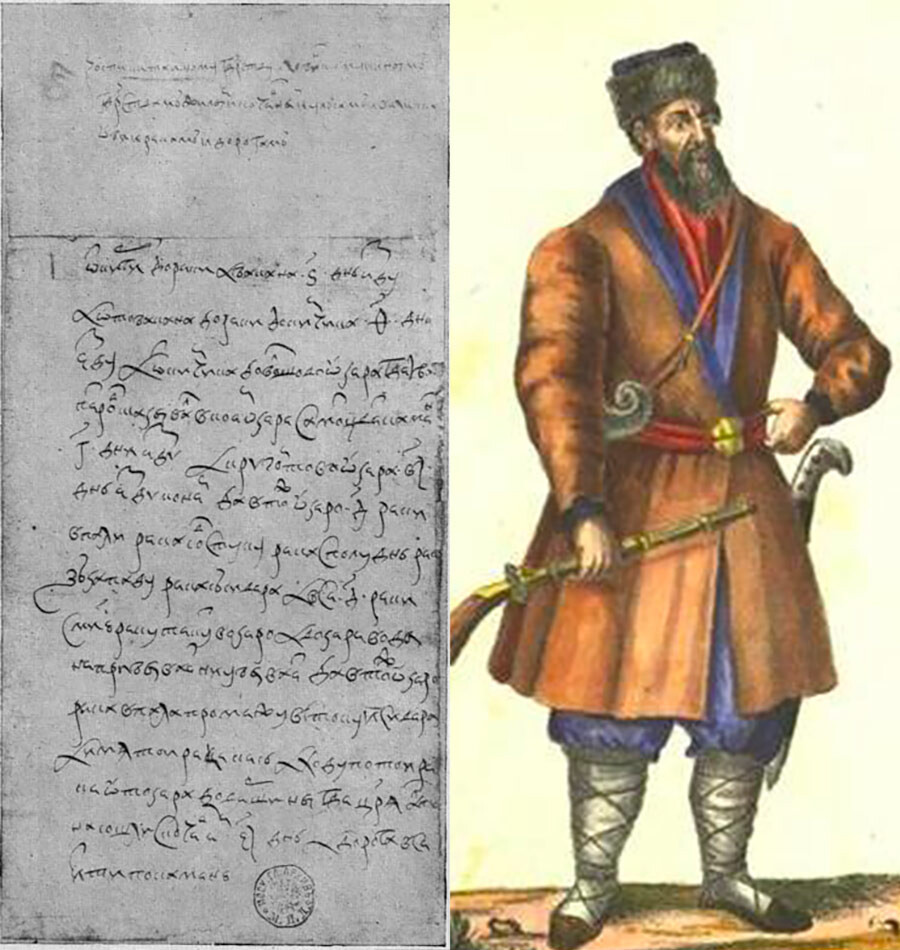

Presumed image of Petlin

Presumed image of Petlin

During the Ming dynasty ( which reigned until 1644), a mission of the Tomsk Cossack Ivan Petlin visited Beijing in 1618. He was not allowed to see the emperor - allegedly because he did not bring gifts from Tsar Mikhail Romanov. But, Petlin was given a letter for the Russian monarch. The document allowed Russians to visit the country, trade within its borders and offered to establish correspondence between the courts. Moscow wasted an opportunity to develop relations with Beijing: the document lay unread for 56 years. However, there were several reasons for that.

For half a century, Russia had no translators from Chinese or Manchurian. Foreigners who could translate the text into Latin or Mongolian and then into Russian, did not want to be privy to secret political matters. In general, the practice of speaking to the Chinese through a “third language” persisted in Russia until the second half of the 18th century, when students of the Russian Spiritual Mission began to translate. (Read more)

On the other hand, there was no urgent need for translation. The organization of Petlin’s mission was instigated by… foreigners. In the early 17th century, England actively sought to lay through the territory of the Russian kingdom a route to eastern India and China and, at the same time, to develop Siberia as a potential center of foreign trade. Moscow avoided the pressure of the British. Their “penetration” threatened the loss of profits from the establishment of trade relations and the emergence of Western missionaries, adventurers and spies in the Russian state.

If the British were to gain access to the vast territories of Siberia and engage in the development of foreign trade there, it would have caused enormous damage to Russia.

When Tsar Mikhail Romanov came to power in Russia in 1613, he provided protectionism in foreign trade to protect it from Western incursions. He also sent expeditions to Siberia and the Far East to establish strongholds. Orders flew from Moscow to establish work on the exploration of trade routes and the development of territories on the ground.

Basically, the letter of the Ming emperor was treated carelessly in the 1620s. More valuable was Petlin’s “Rospis” - a description of the route to China via Mongolia and the countries themselves, the Ob River and plans of the territories. This report played an important role in the further development of Eastern Siberia.

Later, the English ambassador John Merrick managed to send a copy of the “Rospis” to England. During the 17th and 18th centuries, it survived seven reprints in Europe.

Chinese bureaucratic ceremonies

Flag of the 1st Qing Dynasty Emperor of China - Shunzhi

Flag of the 1st Qing Dynasty Emperor of China - Shunzhi

The Manchu dynasty of the Qing (ruled from 1644 to 1912) proved less friendly to Russia than the Ming it succeeded. In the 18th century alone, it unilaterally severed trade relations with Russia 11 times for months and years.

The Russian envoy Fyodor Baykov in 1656 spent six months in Beijing with his embassy in isolation, but never made it to the emperor. Baykov refused the humiliating rite of kowtow, which, according to Chinese ceremonial, would have meant recognition of Russia’s vassal dependence on China.

The merchant Pyotr Yaryzhkin, who was nine months ahead of the diplomat on his visit to China, “set Baykov up”. Yaryzhkin was mistaken for an official envoy; he did not dissuade his hosts and ignorantly made a petition, securing Russia's “vassal status” in the eyes of the Chinese. Baikov was unaware of this episode. Even Tsar Alexei Romanov’s letter did not help him get out of the situation. The ambassador was obliged to deliver it personally to the emperor, but he ended up taking the paper home.

The letter of Tsar Alexei Romanov was delivered to the Chinese by messengers Ivan Perfiliev and Seitkul Ablin in 1662. Fortunately, Moscow demanded nothing more from them than a courier mission. And in 1669 Ablin, who arrived in China as a merchant, was finally received by the new Chinese Emperor Xuan Ye. However, not according to protocol: in a grove, not in a palace.

A Chinese step towards

Scene Recover Signing the "Treaty of Nerchinsk"

Scene Recover Signing the "Treaty of Nerchinsk"

Meanwhile, the situation in the Amur region was heating up. Negotiations were desperately needed. Beijing for the first time sent its delegation to the uncontrolled border territories. It was only partly diplomatic, as it was accompanied by a 15,000-strong army.

The power factor played a decisive role in signing the treaty in favor of China: negotiations were conducted during the siege of Nerchinsk. Russia lost its main stronghold on the Amur, the fortress of Albazin and the Amur region until 1858.

The Nerchinsk Treaty, signed under uneven terms, was legally flawed. However, thanks to it, trade developed, and Peter I even established a state monopoly on “Chinese trade”. Only Russian state caravans could cross the borders.

The Treaty of Nerchinsk - and later the growth of Russia’s power on the world stage under Peter the Great - cemented in Chinese foreign policy the partner status of Russia. (Read more)