Was there a Mongol-Tatar yoke in Russia?

The financial and political dependence of the Russian duchies on their eastern conquerors – Batu Khan and his heirs – is a historic fact. They ruled the realm called ‘Ulus of Jochi’, which first was a part of the Mongol Empire and then became an independent state. In Russia, it was called ‘The Great Tent’ or ‘The Golden Horde’, identifying the entire state with the ruler’s headquarters – similar to how we now say “the Kremlin made a decision”.

However:

– The invaders didn’t call themselves ‘Mongol-Tatars’

– The word ‘yoke’ (‘igo’) was unknown in Russia before the 17th century and the dependence was not called by this Latin word

– The relationship between Russia and the Golden Horde turned from dependence into official relations between neighboring states, in which the Russian lands already played the leading role from the middle of the 14th century.

1. The invaders didn’t call themselves ‘Mongol-Tatars’

Mongol rider, a reconstruction

Mongol rider, a reconstruction

The names of the ‘Mongol’ and ‘Tatar’ peoples are not self-designations. Historians agree that these words were invented by the Chinese.

Mongols:

In China, the nomadic tribes that lived to the north of China were called ‘Mongols’ (‘Menggu’) and the rest of the tribes – ‘Tatars’ (‘Da-dan’) or ‘Mongol-Tatars’ (‘Meng-da’). This tradition was established with the Song dynasty that ruled in China at the end of the 10th century.

The founder of the Mongol Empire Temüjin (aka Genghis Khan, 1155?–1227) belonged to the Mongol house of Borjigin and founded the Genghisid dynasty. Genghisids called themselves Mongols. They borrowed this word from the Chinese, whom Genghis Khan and his descendants conquered at the beginning of the 13th century. Noble ethnic Mongols in Genghis Khan’s realm were military commanders (‘noyons’). The army itself consisted of different tribes that the Genghisids subjugated and used as a brute military force – the Mongols introduced military conscription for all subjugated tribes.

Tatars:

For the Chinese, all the tribes that roamed north of the Great Wall of China were called ‘Tatars’ (‘Da-dan’). The Eastern Siberian Tatars and the Mongol tribes were also called that, although they warred with each other. In the end, the Mongols eradicated almost all the Eastern Siberian Tatars, so the current Siberian Tatars are not their descendants.

The Mongols themselves continued to collectively call all the Asian tribes, mostly Turkic and Turkic-speaking, which they conquered on their way to the Russian lands, ‘Tatars’.

In Russian historiography, the term ‘Mongol-Tatars’ was first used by Pyotr Naumov, a teacher of the 1st St. Petersburg Gymnasium, in 1823, in a textbook.

2. The name ‘yoke’ (‘igo’) was invented by historians

Batu Khan's statue in Kayseri, Pınarbaşı, Turkey.

Batu Khan's statue in Kayseri, Pınarbaşı, Turkey.

‘Igo’ in translation from Latin (‘jugum’) means ‘yoke’. The simplest agricultural yoke, used in Ancient Rome, was in the shape of the letter ‘П’, placed down onto the necks of two oxen. In a metaphoric way, ‘yoke’ means an obligation, a burden. “Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me; for I am gentle and lowly in heart and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light,” Jesus says in the Gospel of Matthew.

Polish historian Jan Długosz in 1479 called the subjection of the Russian lands to the Golden Horde a ‘yoke’ in his ‘Annals or Chronicles of the Famous Kingdom of Poland’. In Russian, this word was first used in 1674 in a historical book titled ‘Synopsis’ by Innokenty Gizel, published in Kiev and very popular in Russia. From there, it was then borrowed by Nikolay Karamzin, who created and substantiated the concept of the ‘Mongol-Tatar yoke’.

3. Why was the method of Nikolay Karamzin non-historical?

Nikolay Karamzin (1766-1826)

Nikolay Karamzin (1766-1826)

Nikolay Karamzin released the first eight volumes of ‘History of the Russian State’ in 1818 – considered the first summarizing work of its kind on the history of Russia. Karamzin worked during the era of Romanticism and was a professional writer. So, he decided to give his work a moralistic nature.

In 1792, in ‘Letters of a Russian Traveler’, Karamzin lamented: “It’s a pity <…> that, to this day, we have no good Russian history work, meaning one written with a philosophical mind, with critique, with noble eloquence <…> We could choose some historical figures, breath life into them, give them color and a reader would be amazed at how Nestor, Nikon and others could turn into something appealing, strong, worthy of attention.” (italics by us – RB).

Karamzin’s “History” was written with a pre-set goal – to show that the Russian people are inevitably moving towards freedom and enlightenment under the leadership of a wise Orthodox Christian sovereign. As Vasily Klyuchevsky wrote: “The goal of Karamzin’s work is to turn Russian history into an elegant edification.”

Hence, describing the invasion of the Mongol army, Karamzin immediately offers an interpretation of this event and, later, proceeds only from it. Describing how Prince Yaroslav II went to the Khan’s headquarters in 1243 to receive the first jarlig to become the Grand Prince of Vladimir, Karamzin clearly states: “As such, our rulers solemnly renounced the rights of an independent nation and bowed their necks under the yoke of barbarians” (that's how Karamzin called the Mongols, who were actually one of the most politically and technically advanced nations of the 12th-13th centuries!)

"The Basqaqs," by Sergey Ivanov. We can see a noble Mongol rider, the basqaq, collecting tributes, and the Russian peasants, who kneel before him in a gesture of respect.

"The Basqaqs," by Sergey Ivanov. We can see a noble Mongol rider, the basqaq, collecting tributes, and the Russian peasants, who kneel before him in a gesture of respect.

The writer doesn’t mention the fact that it was useless to resist Batu Khan. The size of the Mongol army surpassed the combined forces of all Russian princes many times over. Moreover, the Mongol army was a regular one – unlike the Russian princes’ military forces, which were still one the “home guard” level. Karamzin also claims that the Russians back then were a united and independent people – which doesn’t correspond to reality, since Russian duchies were in a constant state of war with each other and were, therefore, not united.

Karamzin’s concept appeared to be very convenient – being a dandy, an encyclopedist and an anglophile, he conceived the idea of Russia “lagging behind” the “enlightened” Europe. “We had our own Charlemagne – Vladimir, our own Louis XI – Tsar Ivan, our own Cromwell – Godunov,” he blatantly wrote. Karamzin didn’t give Russian history its own independent meaning; for him it was only the reflection of the events of European history, hence ‘Tatars’ (actually, the Mongols) for him became “barbarians”. But the yoke, put by the “civilized” Romans on conquered barbarians, according to Karamzin, descended upon the Russian people, rendering them inferior.

4. How did the Mongol invasion impact Russia?

Prince Mikhail at the Golden Horde, by Vasiliy Vereshchagin

Prince Mikhail at the Golden Horde, by Vasiliy Vereshchagin

The invasion of Batu left Russian princes bereft of political independence. The Mongols didn’t want to live in the Russian lands nor rule them directly – they simply needed Russians to pay tributes in money – and men, to serve in the Mongol army. Russian princes became “servicemen” (“subjects”) of the Khan and provided their troops for the Khan’s conquests – to Byzantium, Lithuania and the Caucasus.

With that, the Mongols left to the Rurikids the right of conducting the affairs in their lands – because they didn’t know anything about Russian internal affairs. The Mongols noticed that Russians preferred to die rather than surrender their homes and especially churches, so it was useless to try and enslave them. However, the princes could own their cities only with the permission of the Mongol administration – they needed to go to the Khan, present themselves personally to him and receive a unique document – a ‘jarlig’.

It’s important to know: both the khans and the princes were interested in the population not rebelling, since all of them fed off this population. In equal measure, the khans found it disadvantageous if the Russian princes were attacked from the West with the aim to conquer their lands or if a prince became too powerful without a khan’s “permission”. For example, in 1252, Batu sent his commander Nevryui to support “his” prince, Alexander Yaroslavich (Alexander Nevsky) against his brother Andrey and his allies. Nevryui razed many cities, and took many Russians as captives, while Prince Alexander received his right to rule Vladimir and conducted a census to organize the collection of tribute.

The Desctruction of Ryazan by Batu Khan, 1237

The Desctruction of Ryazan by Batu Khan, 1237

READ MORE: Who was Alexander Nevsky, the heroic Russian saint?

Gradually, from the beginning of the 14th century, the princes began to collect tribute from their people themselves, since the Russians had rebelled against the Golden Horde’s tax collectors – the basqaqs – many times, demanding to expel them from Russian cities. However, from the middle of the 13th century, the Golden Horde suffered the same political fragmentation – there were now several “Great Khans” and each demanded tribute from the Russian princes and strove to issue jarligs. According to historian Nikolay Borisov, “a Grand Prince of Moscow had to either shrink the size of the tribute, split it equally between the ‘heirs’ or deal with just one of them, treating the others as impostors.”

READ MORE: Why were Eastern traditions adopted at the Russian tsar's court?

The Russian princes continued to participate in wars on the side of the Tatars, continued to call Tatar “tsareviches” to their service and to become their allies, while also continuing to marry Tatar princesses and marry their daughters off to Turkic princelings. In the 1250s, Dair Kaydagul, the great-grandson of Genghis Khan, arrived in Russia – he is known to us as Monk Peter, Tsarevich of the Horde. He converted to Orthodox Christianity – and his uncle, Khan Berke, approved of his choice, sending him expensive gifts. Russian nobility considered it to be an honor to intermarry with the noble Tatar lines, because they were, in the view of the Russians, more ancient.

We could continue this list of interactions for a long time, but one thing is clear – what is considered to be a yoke, the enslavement of Russia by a Mongol or Tatar sovereign overlord, in reality was a relationship of divided Russian principalities and Tatar principalities.

Nikolay Karamzin’s opinion that the Mongol invasion “slowed down” the development of Russian lands is also controversial. We have a separate article about that which you can read here.

5. But were Russian princes killed in the Golden Horde? Yes, just like the Horde princes were killed in Russia.

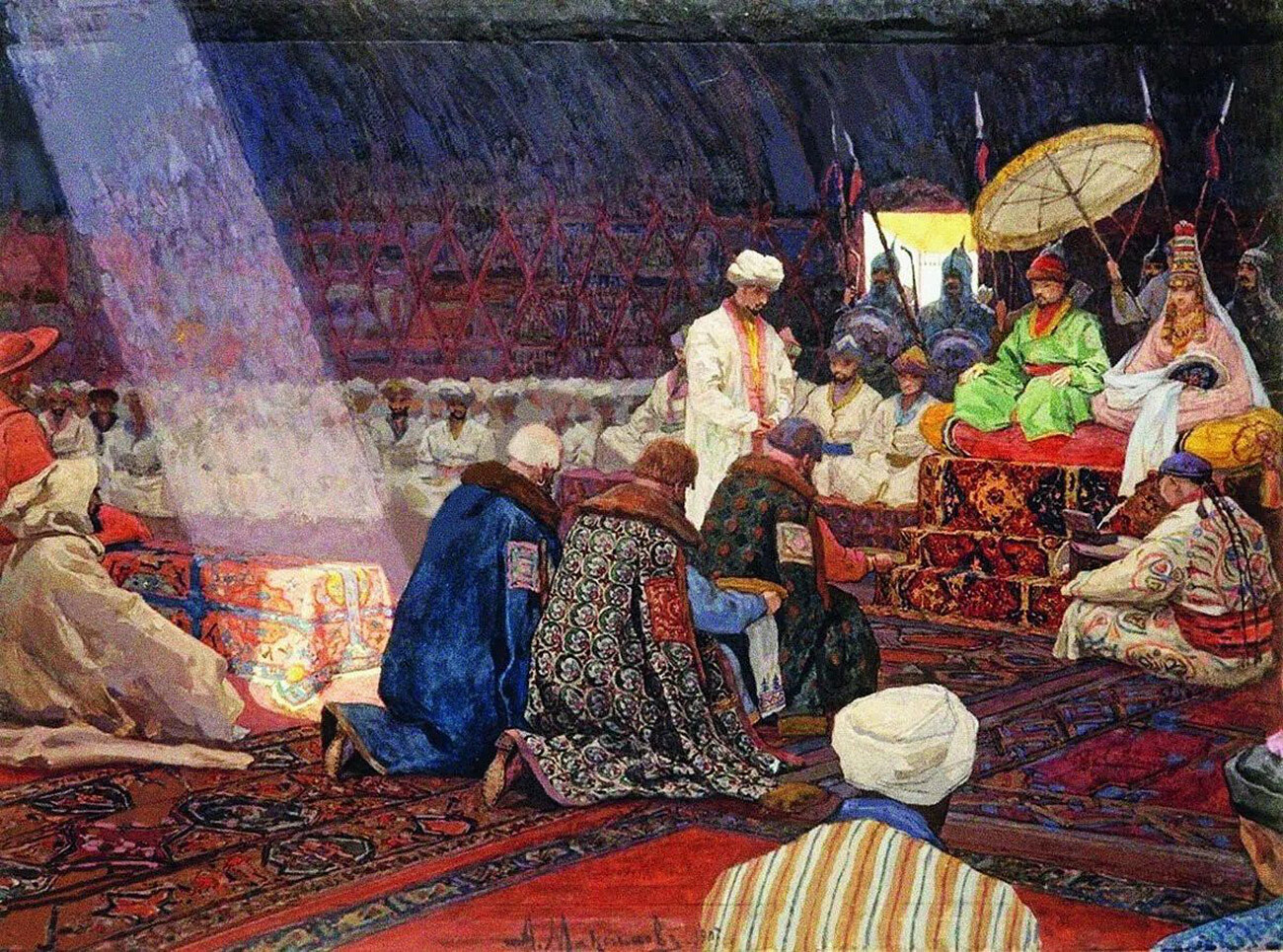

"The Golden Horde," by Alexey Maksimov. We can see the Russian noblemen giving homage to the Khan, standing on one knee.

"The Golden Horde," by Alexey Maksimov. We can see the Russian noblemen giving homage to the Khan, standing on one knee.

Naturally, the Russians and the Golden Horde were enemies. Political dependence and the payment of tribute can’t be based on friendly relations. Princes went to the Golden Horde to receive a jarlig or to be judged by the Khan, who acted as an arbiter in factional disputes. Before these trips, the princes would leave their wills to their wives and sons, realizing that, in the Khan’s headquarters, they could be executed or killed by other princes. In 1325, in Sarai, Prince Dmitry ‘The Fearsome Eyes’ Mikhaylovich caught and killed Prince Yury Danilovich to avenge the death of his father. Prince Dmitry himself was executed a year later for this arbitrariness, by the order of Khan Uzbeq.

The very bad relations between Russians and Mongols started with Russian princes killing Mongol ambassadors, which was a heinous crime. The Golden Horde khans were also killed in Russia – one of the noblest of the Horde khans, who died there, was Shevkal (Chol Khan) – a direct descendant of Genghis Khan in the male line. He was burned alive during the Tver Uprising in 1327.

But, overall, Russians were afraid to capture and kill the Horde nobility, since the latter could avenge it mercilessly. Hence, even when Moscow got rid of its dependency, Russians preferred to welcome the many “Tatar” khans and tsareviches and give them land and even honorary positions at the tsar’s court. Until the end of the 17th century, a “pocket” Qasim Khanate existed, arranged in the middle of Ryazan Region, in order to let its last fearsome rulers live out their days with dignity.