8 curious facts about the ‘Millennium of Russia’ monument

1. The monument marks the emergence of Russian statehood

The monument was erected at the Novgorod Kremlin. Cathedral of St. Sophia (built in 1050) is seen at the background

The monument was erected at the Novgorod Kremlin. Cathedral of St. Sophia (built in 1050) is seen at the background

The year 862 is considered to be the year of the emergence of Russian statehood. According to chronicles, it was in this year when Slavic tribes called on Varangian prince Rurik to rule them. Rurik ascended to the throne in Novgorod, while his brothers Sineus and Truvor – in Belozersk and Izborsk, respectively.

For centuries, this very moment was considered to be the beginning of Russian statehood and the entire Russian history, in total. However, today historians are skeptical about this chronicle version of the founding of Russia and it’s believed to be more of a legend.

But, in the 1850s, Russian authorities were preparing to mark an important date – the millennium of Russia. Sergei Lanskoy, the Minister of Domestic Affairs, suggested erecting a monument to Rurik in Novgorod as to the first Russian ruler. After some deliberation, the Committee of Ministers decided that “the calling of Rurik to rule signifies, doubtless, one of the most important eras of our state”. With that, it was decided that it’s not just the “feat of Rurik” that had to be glorified in 1862; instead, a “people’s Monument “Millennium of Russia’” had to be erected.

2. The emperor personally curated its construction

Bogdan Villevalde. Opening of the Millennium of Russia monument in 1862

Bogdan Villevalde. Opening of the Millennium of Russia monument in 1862

In April 1859, a competition for the monument project was announced. The requirement was to feature the main periods of the history of Russia: from the founding of the state to the liberation from the Tatar-Mongol yoke and the transformation of Russia into an empire.

From 52 projects submitted for this competition, a special commission chose the three that fit the requirements most. In the end, basing their decision on the criteria of symbolism and comprehensibility for the people, the project by artist Mikhail Mikeshin was chosen.

Alexander II personally approved the project. Later, the most minute details and changes were coordinated with the emperor, including the exact height of the monument – as well as the historic figures, the sculptures of whom were made for the monument.

The emperor also oversaw the intermittent stages of work and visited the workshop that was specifically allocated in the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts for the preparation and making of the models. Due to the monument being sculptured, even the painting work for the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, under construction in Moscow, was postponed.

3. The monument consists of three parts and features 128 figures

The compositional foundation of the monument – an orb with a cross, symbolizing the ‘globus cruciger’, one of the main state regalia and a symbol of the authority of the tsar. In total, the monument features 128 sculptures of historic figures.

The upper tier features an Angel, blessing a kneeling woman in a traditional Russian costume. She’s holding a shield with the Russian coat of arms – a two-headed eagle – and the number ‘1862’. This woman symbolizes Russia itself. The scene in total reflects one of the foundations of the Russian state, Orthodoxy.

The upper part

The upper part

The middle tier at the foot of the ‘globus cruciger’ features six scenes – the most important milestones in the history of Russia. Each scene consists of several figures with rulers in the middle – the main heroes of these eras:

- The sculpture of Prince Rurik illustrates the founding of the Russian state (862).

- Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavovich – the Baptism of Russia (988).

- Dmitry Donskoy marks the beginning of the liberation from the Tatar yoke with his victory during the ‘Battle of Kulikovo’ (1380).

- Ivan III – the founding of the monarchic Russian Tsardom (1491).

- Mikhail Feodorovich as the first from the Romanov dynasty symbolizes the restoration of the monarchy after the ‘Time of Troubles’ (1613).

- Peter the Great – the transformation of Russia into the Russian Empire (1721) and the victory over the Swedes.

The middle tear. The sculpture of Prince Rurik is seen in the center

The middle tear. The sculpture of Prince Rurik is seen in the center

The bottom tier around the monument’s pedestal features the figures of the most important people for the history and culture of Russia – educators, state officials, military heroes, writers and artists.

The part of the bottom tier featuring writers and artists

The part of the bottom tier featuring writers and artists

There, you will find great scientist Mikhail Lomonosov, creator of the Russian theater Fyodor Volkov, composer Mikhail Glinka, as well as such famous authors as Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, Mikhail Lermontov, Ivan Krylov and Alexander Griboyedov, among others.

4. A real struggle commenced for the list of featured figures

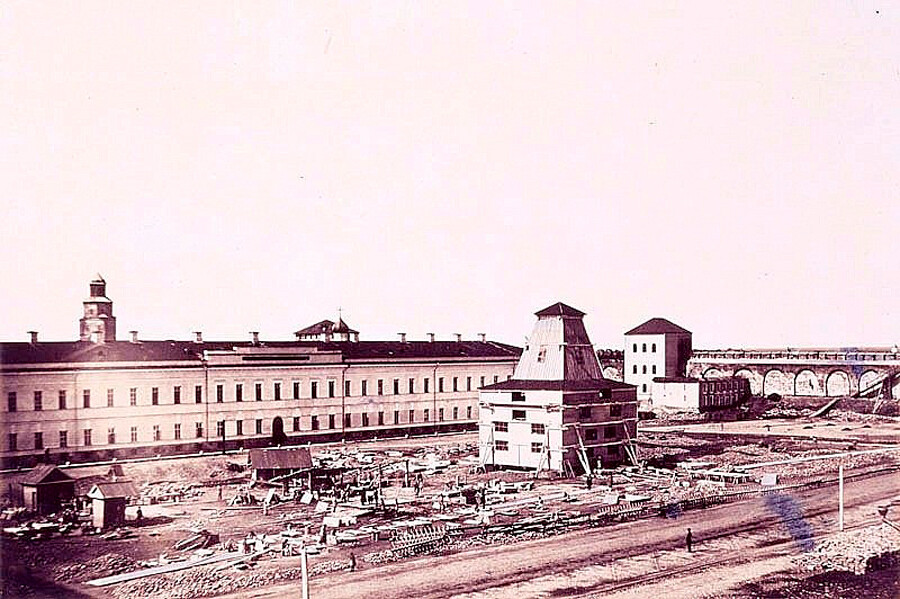

The construction works in 1862

The construction works in 1862

The initial list of figures was composed by artist Mikeshin himself. He couldn’t settle on his choice for a while and brought in historians. The final list was approved by the emperor.

A real struggle commenced for the right to immortalize certain personalities on the monument. The initial list, for example, didn’t have Lermontov or Gogol. The question of whether ‘Malorussian’ poet Taras Shevchenko should have been included or not was discussed for a while (Mikeshin himself insisted on including him but, in the end, the poet didn’t make it on the final list).

At later stages, some church figures were included, including Patriarch Filaret, the father of Mikhail Romanov. On the monument, he’s handing his son Monomakh's Cap, the symbol of the tsar’s authority. Emperor Nicholas I was almost “forgotten”. Emperor Alexander II, his son, never once mentioned that he had to be included – his father wasn’t the most popular of rulers and was considered a “martinet”. But, when he was included, Alexander II didn’t refuse.

Some figures were excluded. Among them were the princes of Ancient Russia, the representatives of the clergy, and some people of culture.

The authorities wanted the monument to be a people’s one. So, as Soviet historians believed, unpopular and cruel personalities weren’t included on it.

For example, the monument doesn’t feature Ivan the Terrible, who executed a lot of people. The list of people who didn’t make it on the monument includes: Catherine the Great, who ruled for 34 years, Alexander I, who liberated Russia and Europe from Napoleon, and other rulers from the 18th and 19th centuries.

5. It was erected during complicated times for the monarchy

The monument 'Millennium of Russia' in 1883

The monument 'Millennium of Russia' in 1883

The construction of the monument coincided with the reforms of Alexander II – serfdom was abolished in 1861. This was a complicated time for the monarchy. At the end of the 1850s, the country was shaken by a wave of people’s uprisings; a lot of underground organizations of a revolutionary nature emerged. A wave of revolutions had already swept Europe; more and more educated youth in Russia were unhappy with the old serf-holding system. The failure of the Russian army in the Crimean war of the middle of the 1850s, when Russia was forced to sign a peace treaty on unfavorable terms and even lost some territories, only added fuel to the fire.

In Soviet times, people insisted that the monument was erected not to mark the millennium of the state but to “promote the inviolability of monarchy in Russia”, to “bolster the shaking throne of Russian tsars with this monument”, as historian Andrey Zakharenko wrote in 1957.

In 1928, in an academic work of the local Novgorod Museum, it was even called “the monument to the Millennium of monarchic oppression”.

6. It was partially built with public funds

Emperor Alexander II attended the opening ceremony

Emperor Alexander II attended the opening ceremony

A fundraising campaign was announced for the construction of the monument. People donated sums ranging from literally half a kopeck to quite large amounts of 30 rubles in silver, which during the era of Alexander II, was equivalent to about 300,000 modern rubles. The authorities announced that they required a sum of 500,000,000 rubles for the construction, which is approximately 5 billion modern rubles!

However, only a third of the required sum was raised and the rest of it was taken from the treasury. The final cost of the construction rose to approximately 50,000.

7. The monument brought fame to its creator

Ilya Repin. Portrait of Mikhail Mikeshin, 1888

Ilya Repin. Portrait of Mikhail Mikeshin, 1888

When Mikhail Mikeshin began his work on the monument, he was only 24. He was a little-known beginner artist, despite the fact that one of his paintings had already been purchased by Emperor Nicholas I. He had never worked with sculptures prior to that, especially on such a scale. That’s why he brought in famous sculptor and his teacher Ivan Schröder for the creation of the monument.

The project became a lucky ticket for Mikeshin. Right after the monument was opened in Novgorod, he was awarded the Order of Saint Vladimir fourth-class and he was assigned a solid lifetime pension.

Monument to Catherine the Great in St. Petersburg. By Mikhail Mikeshin

Monument to Catherine the Great in St. Petersburg. By Mikhail Mikeshin

At just 34 years of age, he was awarded the title of an academician of the Academy of Arts and he was literally flooded with commissions of monuments of the highest persons. In the end, he created a monument to Catherine the Great in St. Petersburg, a monument to Alexander II in Rostov-on-Don, as well as a monument to Bogdan Khmelnitsky in Kiev.

8. Was almost destroyed by the Nazis

The Kukryniksy art group (Mikhail Kupriyanov, Porfiri Krylov, Nikolai Sokolov). Fleeing of the Nazis from Novgorod, 1944-46

The Kukryniksy art group (Mikhail Kupriyanov, Porfiri Krylov, Nikolai Sokolov). Fleeing of the Nazis from Novgorod, 1944-46

The monument to “monarchy” miraculously survived during the revolutionary years, but it could have perished during World War II. In Summer 1941, Novgorod was besieged by the Nazis; they decided to transport the bronze monument to Germany. The dismantling took quite a long while and they managed to transport only its bronze grating. When Soviet troops entered the city in 1944, they discovered that the majority of sculptures were scattered around and only half of the orb – the ‘globus cruciger’ – remained on the pedestal. Soviet authorities decided to restore the monument and, in record time – in less than a year – all the figures returned to their places. More than 1,500 details of the monument that disappeared were made anew.