Where did the garbage go in Tsarist Moscow?

In ancient times, there was little garbage. Almost everything valuable – clothes, dishes, household items – was used and repaired until it finally fell apart. Clothes were re-stitched and when they were in complete disrepair, they were used as rags or lint (threads obtained by unraveling old linen cloth – they were used as surgical dressing, for instance). All scraps leftovers from the table were fed to the livestock, broken wooden objects were burned and paper, of course, was saved.

And yet, Moscow was already a big city in the 15th century and there was more garbage than the citizens had time to collect and process. One of the main problems was human and animal waste, which, due to population growth, became an urban problem already in the 17th century.

Nightmen: What was instead of sewage

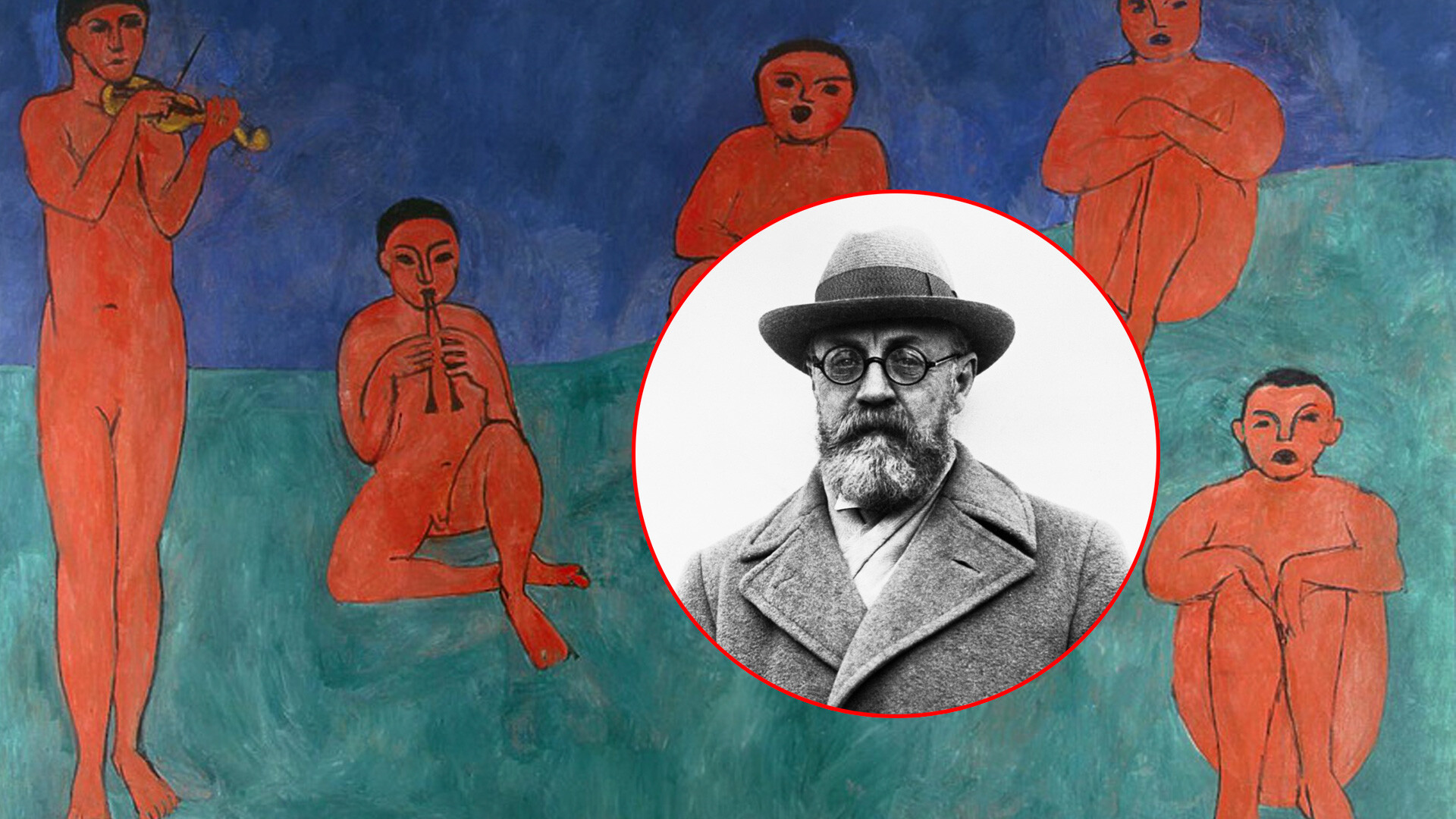

Zolotars (sanitation team) in the 1910s, Russia

Zolotars (sanitation team) in the 1910s, Russia

Ancient Muscovites were exquisite slobs – like the entire urban population of medieval Europe. Garbage and impurities were thrown directly into the street. The resting places in the chambers of noble people often went out into the backyard or into the alley. Only the main streets were “paved” and mostly with wooden boards. Most of the streets were covered with mud mixed with dung and human excrement. The dung attracted flocks of sparrows and, in spring, when everything thawed, the inhabitants took the dirt from the streets to the vegetable gardens on their dachas near Moscow.

Up to the middle of the 17th century, street cleaning and sanitary norms were out of the question. And, even after the plague epidemic happened in Moscow and the central region in 1654, which killed up to a third of the population, nothing changed until 1699. Then, Tsar Peter issued a short law ‘On the observation of cleanliness in Moscow and on the punishment for throwing rubbish and all kinds of litter into the streets and alleys’ – now it was punished with a whip, with a fine levied after.

READ MORE: Riots in Russia during quarantines

That's what most streets looked like in Moscow in the early 20th century.

That's what most streets looked like in Moscow in the early 20th century.

But, it took another plague epidemic in 1771 for Moscow authorities to oblige homeowners to make cesspools; and, to clean them, they introduced the first sanitation team. In Russia, a member of a sanitation team was called ‘zolotar’ (‘золотарь’), – a name ironically derived from the word for gold, ‘zoloto’ (‘золото’). ‘Zolotars’ were also called ‘zolotaya rota’ (‘золотая рота’), ‘the golden company’.

At night, they rode through the streets of Moscow with barrels and pumped out the contents of cesspools for a minimal fee. At first, criminal offenders serving sentences for petty crimes were appointed as ‘zolotars’ – they were pardoned as part of their sentence for their service. Gradually, poor freelancers became ‘zolotars’ – it was work, after all, plus there is a small chance to find money or jewelry among the dung.

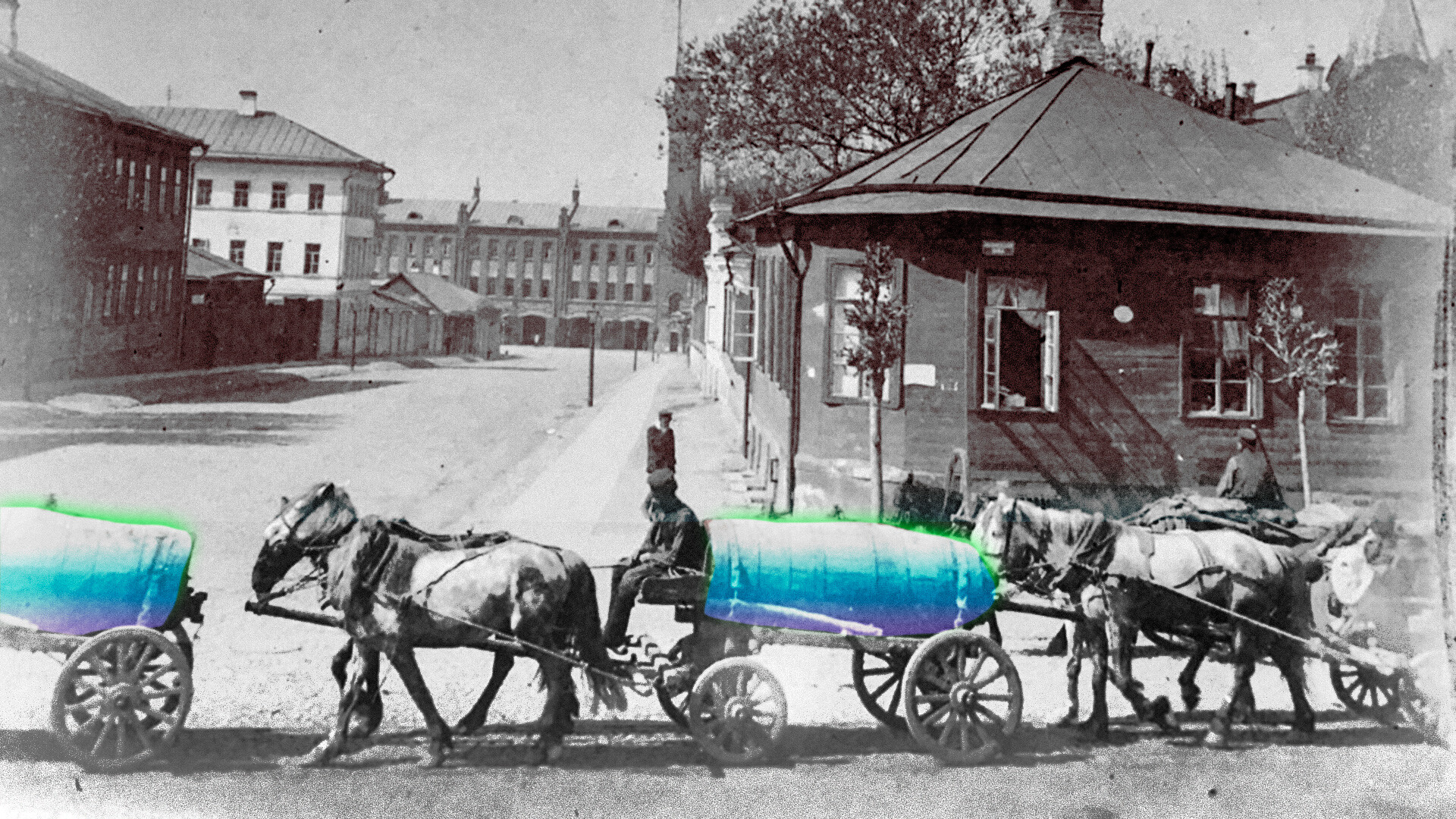

Sanitation team in 1904 in Moscow – you can see the long line of barrels

Sanitation team in 1904 in Moscow – you can see the long line of barrels

The ‘golden company’ worked at night, because their work was very “fragrant”. In the 19th century, these “goldsmiths” were nicknamed ‘Brocards’ for this, after the name of a famous perfume company.

“Early in the morning, a cart with barrels rumbled past our windows – the ‘zolotars’ were shaking on a simple cart with long elastic poles for leaf springs, melancholically tugging the horses and snacking on a fresh ‘kalach’ with relish. Passersby then turned away, clamped their noses and muttered: ‘‘The brocard is coming!’,” recalled Muscovite and theater critic Yuri Bakhrushin.

Having traveled around the part of the city for which they were responsible, the ‘zolotars’ drove to the outskirts, beyond the city border, and poured the contents of their barrels into the water bodies or the lower reaches of the Moscow River. In the Lefortovo district, there still is a street named ‘Zolotaya’, which crosses the former Kamer-Kollezhsky rampart – which was once used by the ‘zolotars’ to carry their cargo to the outskirts beyond the Vladimirskoye Highway.

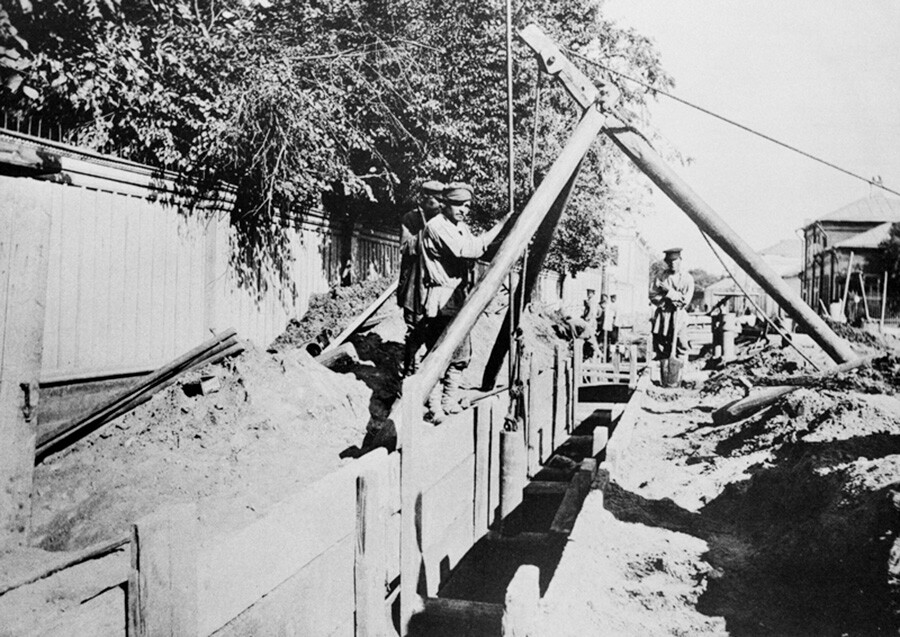

Construction of Moscow sewage system, 1898

Construction of Moscow sewage system, 1898

By the mid-19th century, Moscow was surrounded by a ring of human waste. The historian Nikolai Kareev recalled: “When approaching Moscow on horseback, one plugged one’s nose against the stench spread by sewage dumps and when railroads appeared, the windows in the carriages were closed for the occasion. Historian Solovyov in this respect compared Moscow to Saturn, around which there is also a ring.”

Of course, Muscovites tried in every possible way to save money on the services of 'zolotars' – they poured and scooped out their cesspools outside the fence, on empty plots, directly into the street. From 1875, the Moscow City Council began to issue mandatory regulations on sanitation. They determined the exact time of removal of sewage, routes of wagons, issued rules on the device of cesspools and waste places.

Lyublinskie irrigation fields, Moscow. The administration buildings

Lyublinskie irrigation fields, Moscow. The administration buildings

But all the rules and fines were powerless against the low culture of everyday life. The newspaper ‘Russian Chronicle’ in 1871 reported about the center of Moscow: “Follow the stench. Here is the Red Square and on it the only monument in Moscow to the liberators of Russia in 1612. Around it, there is contamination from stinking streams flowing along the sides. In the depths of the trading rows, the city taverns are covered in dirt and stench. From the courtyards often whole streams of stinking filth flow directly into the streets.”

Lyublinskie irrigation fields, Moscow

Lyublinskie irrigation fields, Moscow

Only in 1893 did the Moscow authorities finally start to build sewerage and equip Lyublinskie and then Lyuberetskie irrigation fields, where the sewage passed soil purification. Which meant, ‘zolotars’ roamed the Moscow streets until the 1930s.

Household garbage: Landfills & junk yards

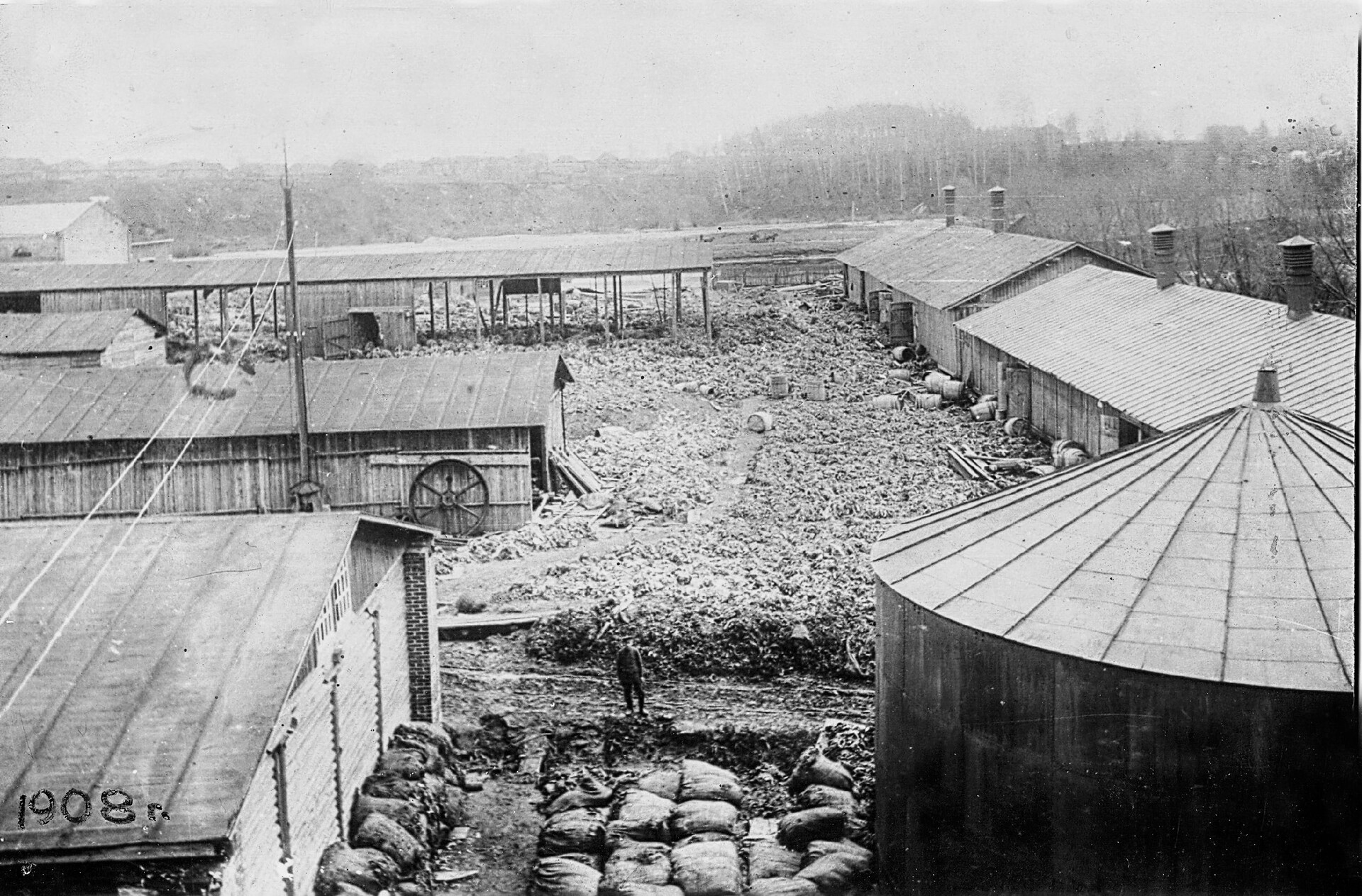

Junk yard in Kondrovo, near Moscow, 1908

Junk yard in Kondrovo, near Moscow, 1908

As Moscow’s population grew, so did the amount of household garbage. There were no longer enough dogs to eat all the leftovers of pork and cow carcasses, sold by the thousands in Okhotny Ryad and so, ragmen appeared.

Historian George Andreevsky writes: “In the middle of the 19th century, wagons with the bottom covered in galvanized iron appeared in the Moscow streets. Covered with dirty and torn tarpaulin or burlap, they slowly dragged through the streets. Passersby clutched their noses at the unbearable stench and the occupants of the houses closed their windows.” These carts collected bones, veins, hooves, heads of slaughtered cattle and took them to bone, soap, glue factories located on the outskirts of the then city – beyond the current Third Transport Ring.

A Russian ragman, the 1900s

A Russian ragman, the 1900s

Garbage was collected from most of the city yards by rag pickers. They went around the city and looked for rags, old iron, waste from the production of shoes and clothes and other junk. In a day, according to Andreevsky’s estimation, 100-150 kilos of garbage could be collected.

The rag maker took his piles to the rag warehouse, where they were handed over by weight. At the warehouse, the junk was sorted: rags went to paper factories, bones – to glue factories, glass – to glass factories, and the surviving bottles and jars could be sold to a china store.

A Tatar rag picker, 1903-1904, Moscow

A Tatar rag picker, 1903-1904, Moscow

But, there were maybe 100-200 ragmen for the whole of Moscow – too few for a large city. That’s why there were spontaneous dumps outside the city anyway. The newspaper ‘Moskovskie Vedomosti’ wrote: “Behind the Dorogomilovskaya outpost, in the village of Fili, a garbage dump is being made in a deep ravine. The other day, two garbage collectors who stayed overnight in this ravine suffocated to death after they were covered with garbage. Along with them, other scavengers who managed to crawl out from under the garbage slept in dug-out kennels. They informed the local peasants about the collapse, with the help of which the corpses of the two unfortunate homeless people were dug up.”

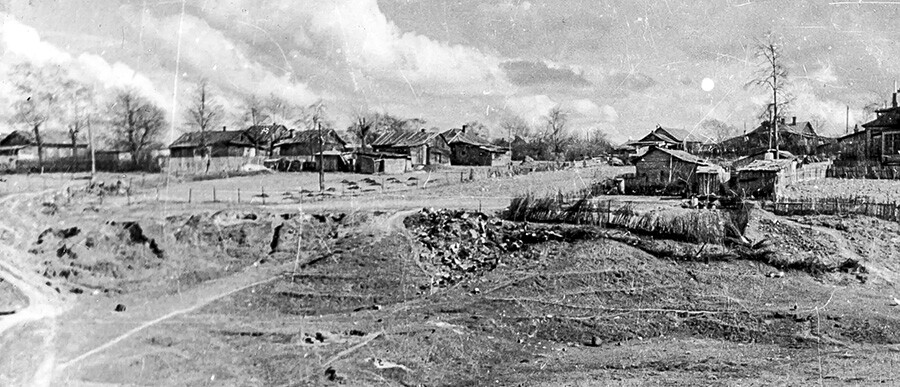

Fili village. A part of the garbage dump can be seen in the center of the photo.

Fili village. A part of the garbage dump can be seen in the center of the photo.

At the turn of the 19th-20th centuries, Moscow was in a situation of garbage crisis – sewage and dumps were absorbing the city. A problem that had to be solved by the Soviet authorities.