5 Americans who emigrated to the USSR during the Great Depression

1. Leon Sachs (1918 – 1977)

Leon Sachs (center) as a 1st year student of the Moscow Conservatory. With his teacher David Oistrakh (right) and his teacher Peter Stolyarsky (left).

Leon Sachs (center) as a 1st year student of the Moscow Conservatory. With his teacher David Oistrakh (right) and his teacher Peter Stolyarsky (left).

Leon Sachs came to the USSR when he was just seven years old. His parents were from the Russian Empire, but he was born in Canada. In 1925, his father, a communist, decided to respond to the USSR’s call to socialist workers of all the world and move to Moscow. Leon showed musical talent as early as 4, when he started learning to play violin. His parents were poor, but they did everything to support their son’s talent.

In Moscow, however, Leon was able to study and practice violin for free, thanks to a special tuition for gifted children from the Soviet government. “Sachs is a serious and sufficiently accomplished musician, technically. A natural taste, rhythmic sense, fine finger work are Sachs’ best qualities,” ‘Moscow Daily News’ wrote about him in 1935. By 1937, he had entered the Moscow Conservatory, studying under the supervision of famous violinist David Oistrakh.

Teacher Leon Sachs with his class. 1952.

Teacher Leon Sachs with his class. 1952.

In 1941, Leon Sachs was drafted into the Soviet Army and served in the Red Army Central House Symphony Orchestra for three years. During the harshest era of the USSR, Leon met his wife, pianist Muza Denisova, with whom he had two children. After the war, Leon Sachs started working at the Bolshoi Theater and became the principal violin player of its orchestra, as well as its concert director. He died in 1977 while on a concert tour in Greece.

2. Lloyd Patterson (1911 – 1942)

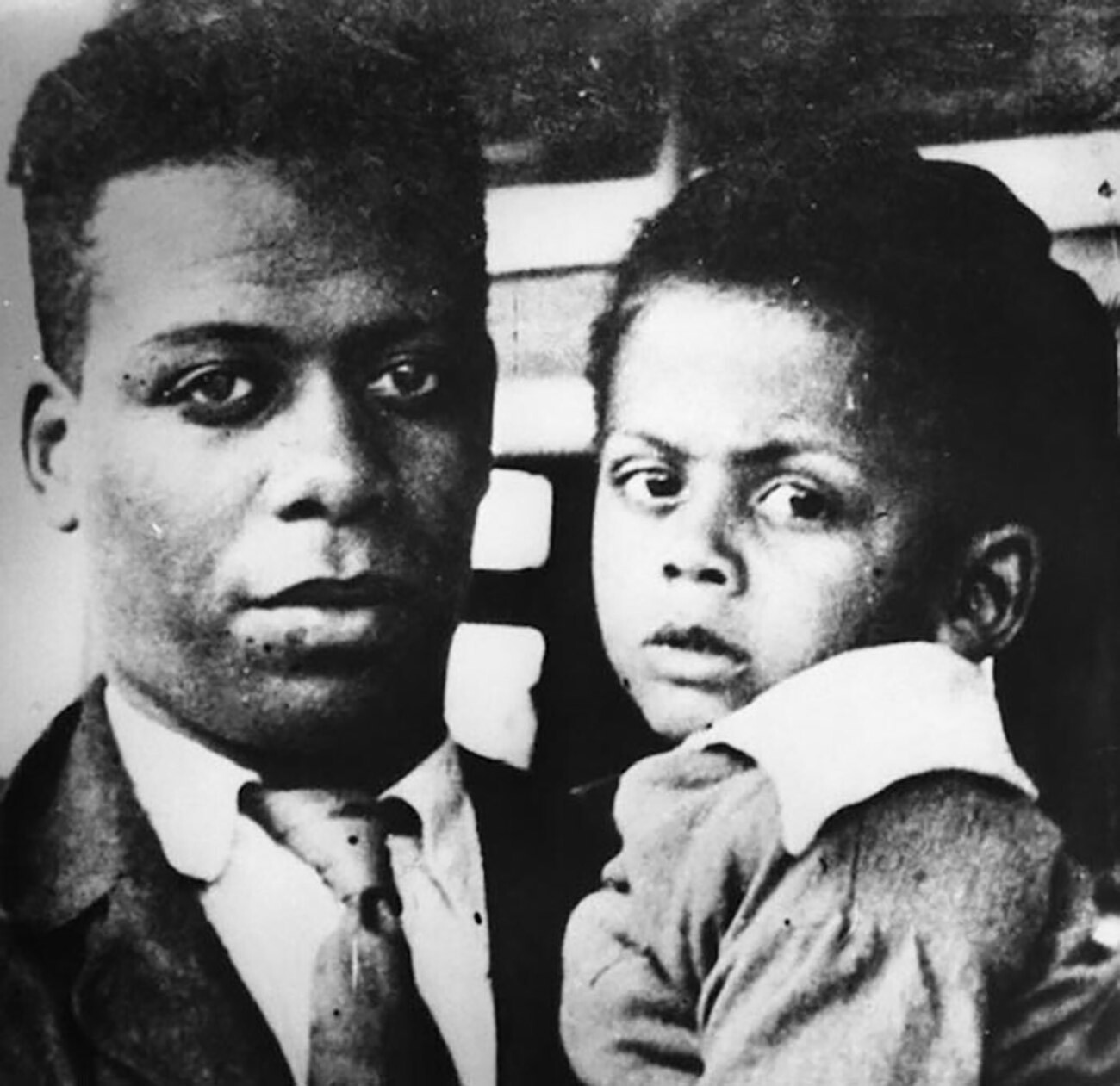

Lloyd Patterson with his son James

Lloyd Patterson with his son James

Lloyd Patterson grew up in New York, where he studied interior design, but, because of the raging racism in the U.S., in 1932, Patterson went to the USSR, the state that propagated racial equality. In Moscow, he was to participate in the filming of ‘Black and White’, a movie about racial prejudices, Although the filming was eventually canceled, Patterson stayed in Russia.

In Moscow, Lloyd met Vera Aralova, a Ukrainian-born fashion designer and artist and daughter of a Soviet military intelligence officer. Although marriages to foreigners were looked upon wary by the USSR’s authorities, they made an exception because of Vera’s father. Patterson and Aralova had three children. He worked as a designer in Moscow and also became a news announcer, one of the few native speakers of English on Soviet radio.

Vera Aralova, designer, Lloyd Patterson's wife

Vera Aralova, designer, Lloyd Patterson's wife

As World War II started, Patterson’s family was evacuated to Siberia, but he stayed in Moscow. During one of the Nazi bombings of Moscow in 1941, Patterson suffered a concussion. He was evacuated to Siberia, where he reunited with his family. He died a year later in Komsomolsk-on-Amur.

READ MORE on Patterson: A black family’s journey from the USA to the USSR and back (PHOTOS)

3. Margaret Yefremova, nee Wettlin (1907 – 2003)

Margaret Wettlin

Margaret Wettlin

Born into a Newark Methodist family, Margaret did great at school and college and went on to become a teacher of English language and literature. She then worked as a high-school teacher in Media, Pennsylvania, until 1932. However, as the Great Depression started, Margaret became more disillusioned with the U.S.’s internal policy and decided to try going to the USSR for a year.

In Russia, Margaret eventually went to Nizhny Novgorod, where, at the automobile plant, many American citizens were working and living with their families. Margaret got a job teaching their children. In Russia, she met Andrei Yefremov, a stage director and a close associate of Konstantin Stanislavski. Yefremov became Margaret’s husband in 1934 and, a year later, they had a son.

When, in 1937, the Soviet government decided that foreigners living in the USSR either had to take up Soviet citizenship or leave the country for good, Margaret chose to stay. She joined the staff at the Foreign Language Institute in Moscow.

READ MORE: What punishment could a Soviet citizen get for marrying a foreigner?

In Moscow, Margaret was forced by the KGB to report on her and her husband’s friends and acquaintances, which often resulted in their “disappearance”. She never wanted to do this, but secret services kept threatening her. During World War II, Margaret accompanied her husband, who was establishing entertainment units for Soviet soldiers, often close to the front. Later, they managed to escape to the Caucasus.

It was after the war that Margaret started studying Russian literature. She would later publish a book on famous playwright Alexander Ostrovsky. She also authored Russian Road, a book on her travels across the USSR. After Andrei Yefremov died in 1968, Margaret thought about going back to the U.S. She was allowed to do so by the Soviet KGB, because of all the reporting work she did for them.

She did a trip to the U.S. in 1973 and, eventually, moved back there in 1980. Her daughter and grandson moved to Philadelphia with her, while her son remained in the USSR, but he and his family rejoined with his mother seven years later. Margaret Wettlin died in 2003 in West Philadelphia.

4. Oliver John Golden (1892 – 1940)

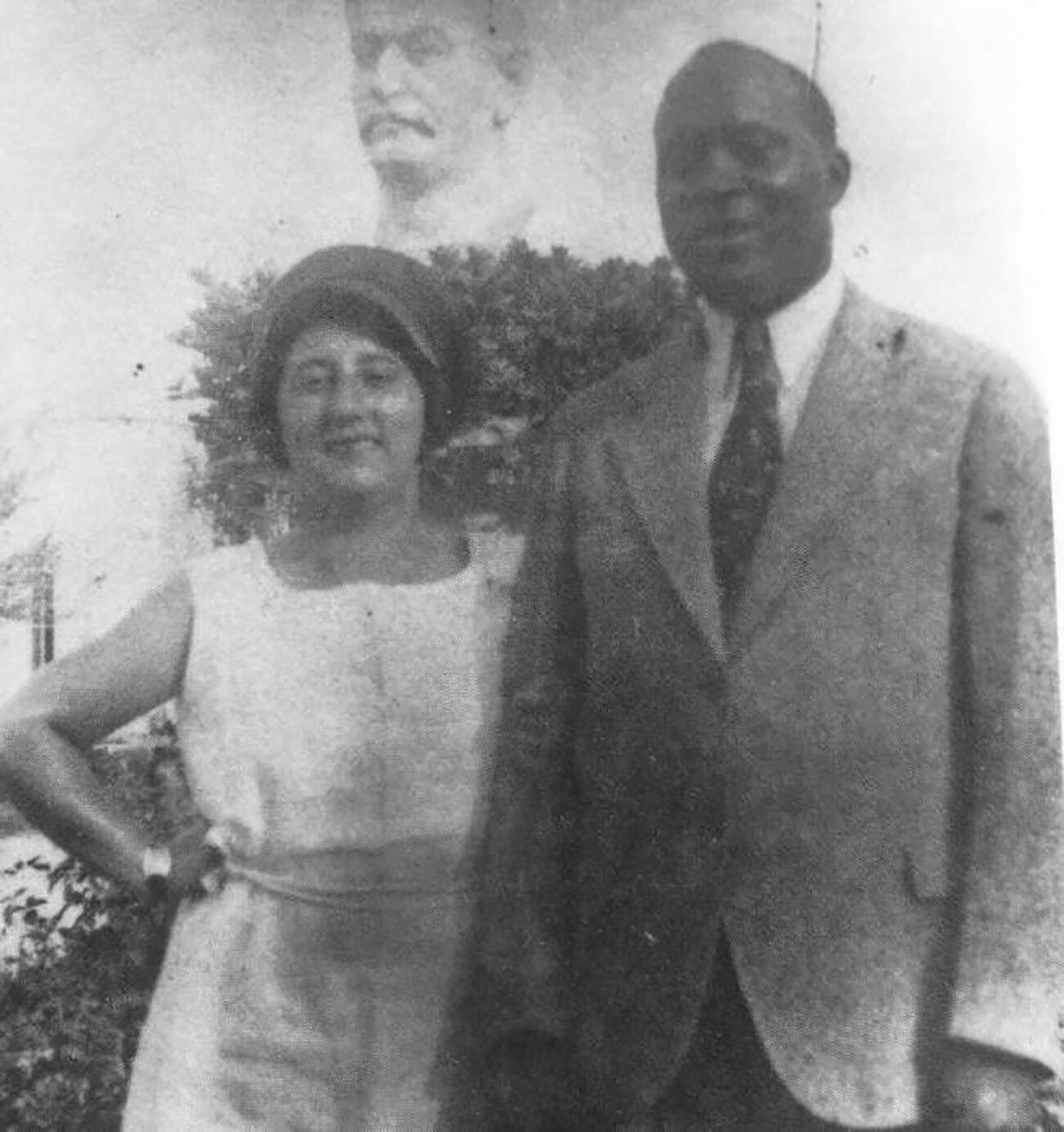

Bertha and Oliver John Golden

Bertha and Oliver John Golden

Unlike many other black men descending from cotton-picking families, Oliver Golden went on to make cotton agriculture his main field of work. His father used to be a cotton-picking slave, but after the liberation, became a wealthy farmer. Oliver himself studied agriculture under another black scientist, George Washington Carver.

In 1930, George Carver helped Golden to gather a group of black agricultural scientists to send them to the USSR. There were 16 of them and Oliver went to the USSR with his wife Berta Byalek, a Polish emigrant. They went to Leningrad first and then – to Uzbekistan.

Golden was aware of the potential of the cotton industry in Uzbekistan. They also considered the fate of many native Uzbeks, who were picking cotton in dire heat, alike to their own fate during the years of slavery and wanted to help develop the cotton industry in the Asian republic.

What is more, the USSR didn’t have racial segregation in terms of work pay. Based in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, the group of scientists worked on after their initial contracts ended and many of them stayed in Uzbekistan.

Golden died there in 1940, survived by his wife and daughter, Lily Golden. Lily became a famous Soviet and Russian historian and advocate of the black people’s rights.

5. Thomas Sgovio (1916 – 1997)

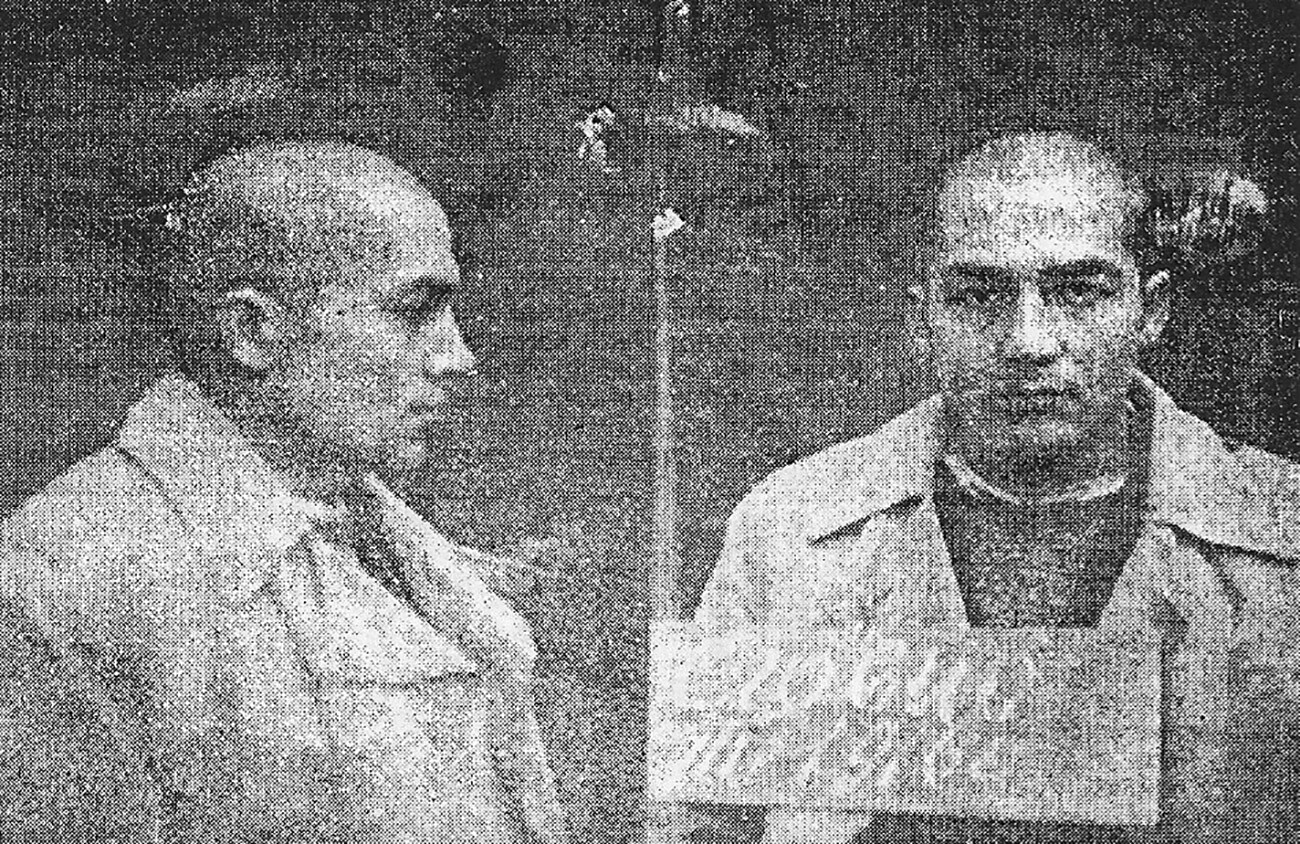

Thomas Sgovio's camp mugshot

Thomas Sgovio's camp mugshot

Just like Leon Zachs, Thomas Sgovio went to the USSR following his communist father. In 1935, Joseph Sgovio was deported from the U.S. “as a communist agitator”. Upon arrival, Sgovio destroyed his American passport.

He wanted to continue his education as an artist, but he wasn’t accepted into any art schools in Moscow. He worked as a magazine illustrator. After three years, Thomas became disillusioned with the Soviet regime and went to the U.S. embassy to try to reclaim his American citizenship, but was arrested by the NKVD immediately after leaving the embassy. This began his long and dark journey through the Soviet GULAG system.

At the initial inquiry, Thomas didn’t deny his wish to leave the USSR. This, in the eyes of the Soviet secret service officers, meant his disillusionment with the Communist ideas, which he also didn’t deny – so he was sentenced to forced labor as a socially dangerous element.

"Our train left Moscow on the evening of 24 June. It was the beginning of an eastward journey which was to last a month. I can never forget the moment. Seventy men ... began to cry" – Sgovio wrote about the moment the train with the convicts was leaving for Vladivostok.

READ MORE: Horrors of the USSR through the eyes of 3 Americans

As an artist, Sgovio unexpectedly became an important figure in the labor camps. The culture of prison tattoos was very important in the Russian prison system back then, and Sgovio was constantly busy making tattoos. At least, that made his life in the camp a little bit better, because the criminal bosses protected him.

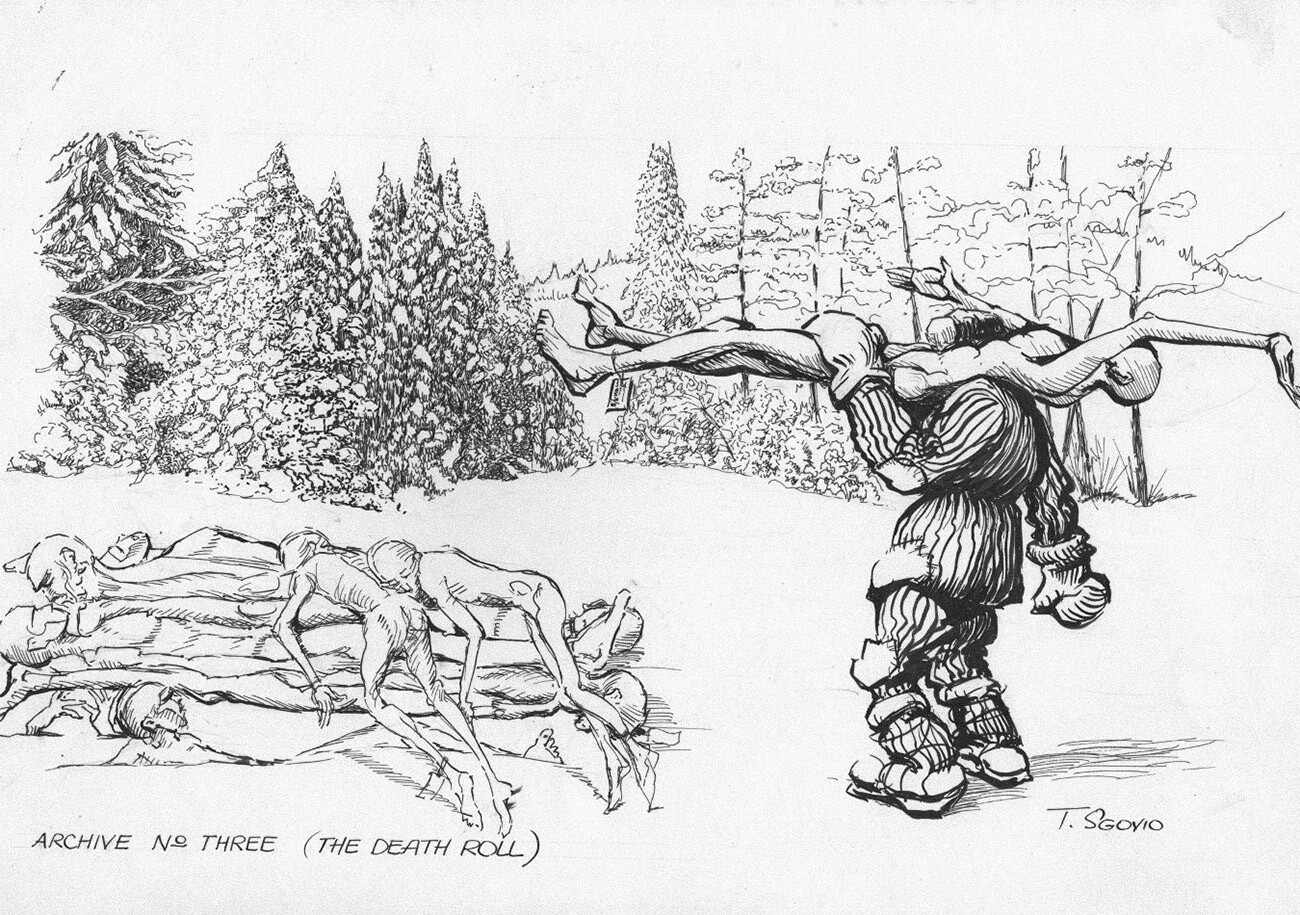

Piling of corpses in the "Death Valley"

Piling of corpses in the "Death Valley"

In about 10 years, Sgovio left the camps and was allowed to settle in the Far East. In 1956, he was able to return to Moscow, and in 1960, finally left back to America, where he authored a book, Dear America! Why I Turned Against Communism. During his time in the camps, Sgovio witnessed a lot of horrors and atrocities, which he described and condemned in his book. His accounts are an important historical source concerning the dire state of affairs in the Far East camps after WWII.

Thomas Sgovio lived the second part of his life in the USA, married and had children. He died in 1997 in Mesa, Arizona.