What haircuts did men wear in Tsarist Russia?

The Russian bylina (epic) about the hero Dobrynya Nikitich has the following lines: "The young Dobrynya Nikitich had yellow curls... and your hair, poor drunkard, hangs down to your shoulders!" Since ancient times, men in Russia have always taken care of their hair and beard.

Hairstyles before Peter the Great

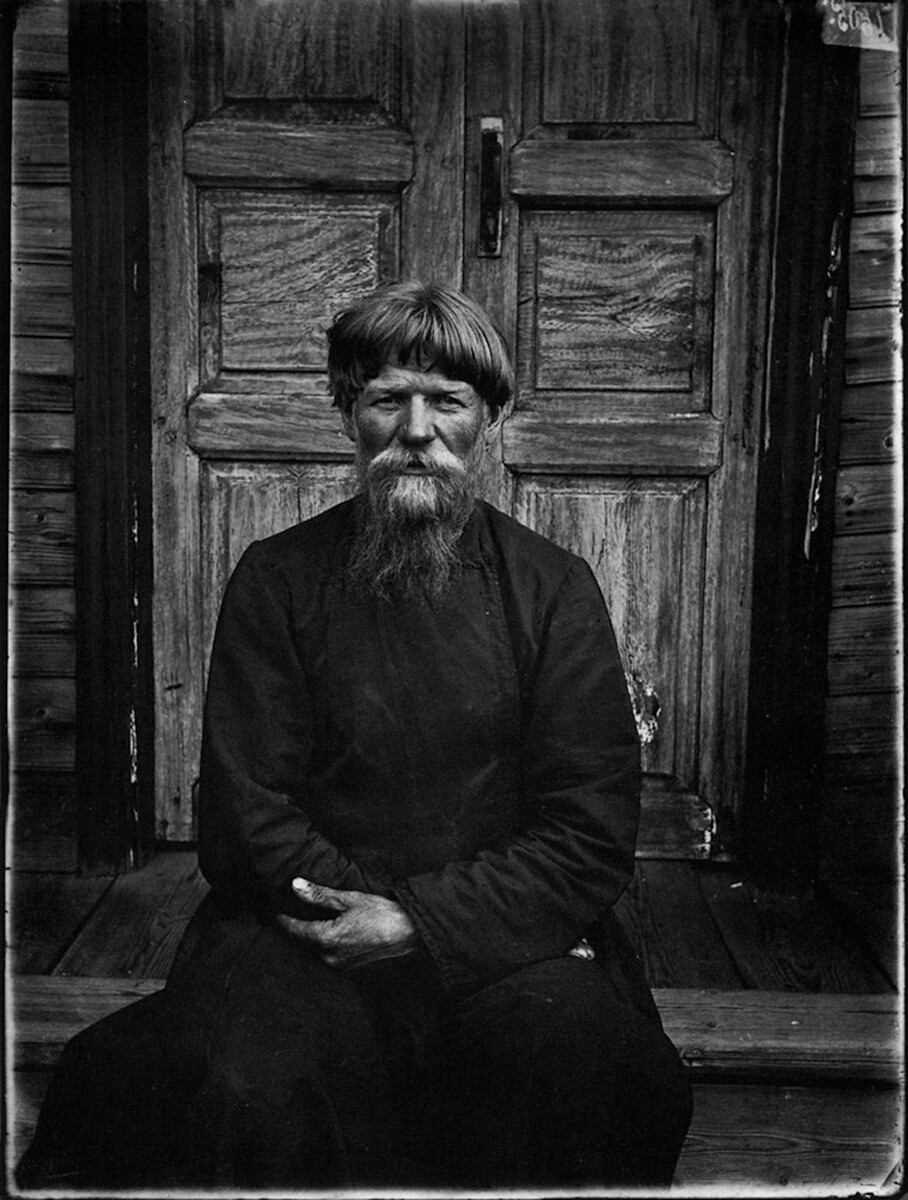

Haircut 'in a circle' ('under the pot') on an Old Believer from Nizhny Novgorod region

Haircut 'in a circle' ('under the pot') on an Old Believer from Nizhny Novgorod region

Uncut and unkempt hair on a man was considered a sign of either a drunkard or being bewitched, or insane. Only outcasts and marginals did not get their hair cut. Also, those who fell into disgrace from the good graces of their ruler, whether a medieval prince, or later, the tsar, stopped cutting and washing their hair (and stopped combing their beard) as a sign of protest to show the extent of their despair and remorse.

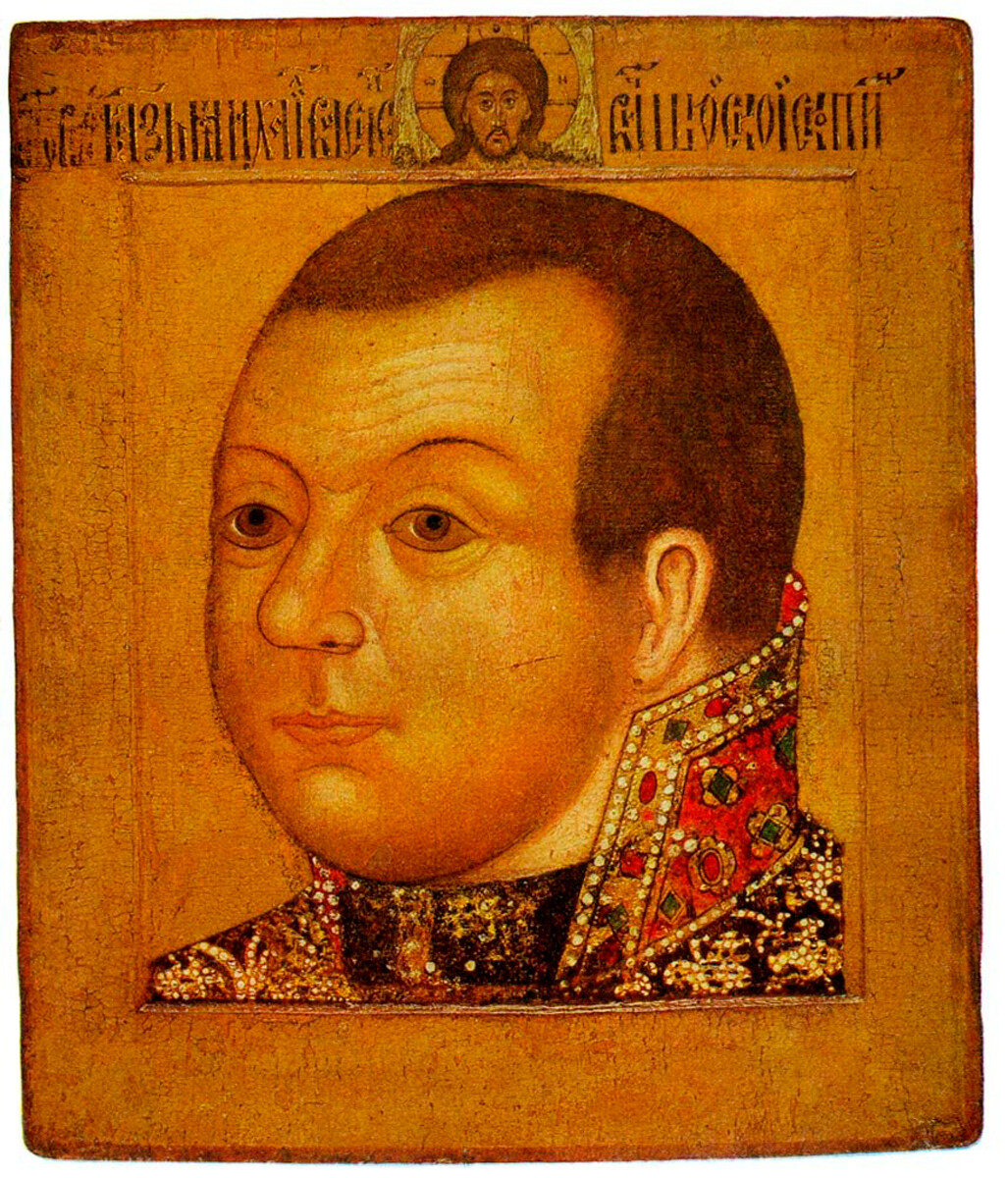

Mikhail Skopin-Shuyskiy, a Russian war commander, 1610. Mikhail was just 23 when he died, and he didn't wear a beard. His hair is short – such a haircut was common for military men

Mikhail Skopin-Shuyskiy, a Russian war commander, 1610. Mikhail was just 23 when he died, and he didn't wear a beard. His hair is short – such a haircut was common for military men

Men in Tsarist Russia wore semi-long hair that covered the back of their heads. Then the haircut "in a circle" (в кружок) spread, which we also call "under the pot" (под горшок) – to do this a pot was literally put on one’s head and the hair sticking out from under its edges was cut. In the 16th century, during the reign of Ivan the Terrible, a fashion arose to shave one's head. This came about under the influence of the Tatar princes because during long military campaigns this was necessary from a sanitary point of view. This fashion, however, spread only among the nobility – the common folk considered such a hairstyle as belonging to the “enemy”. The head was shaved once every two weeks.

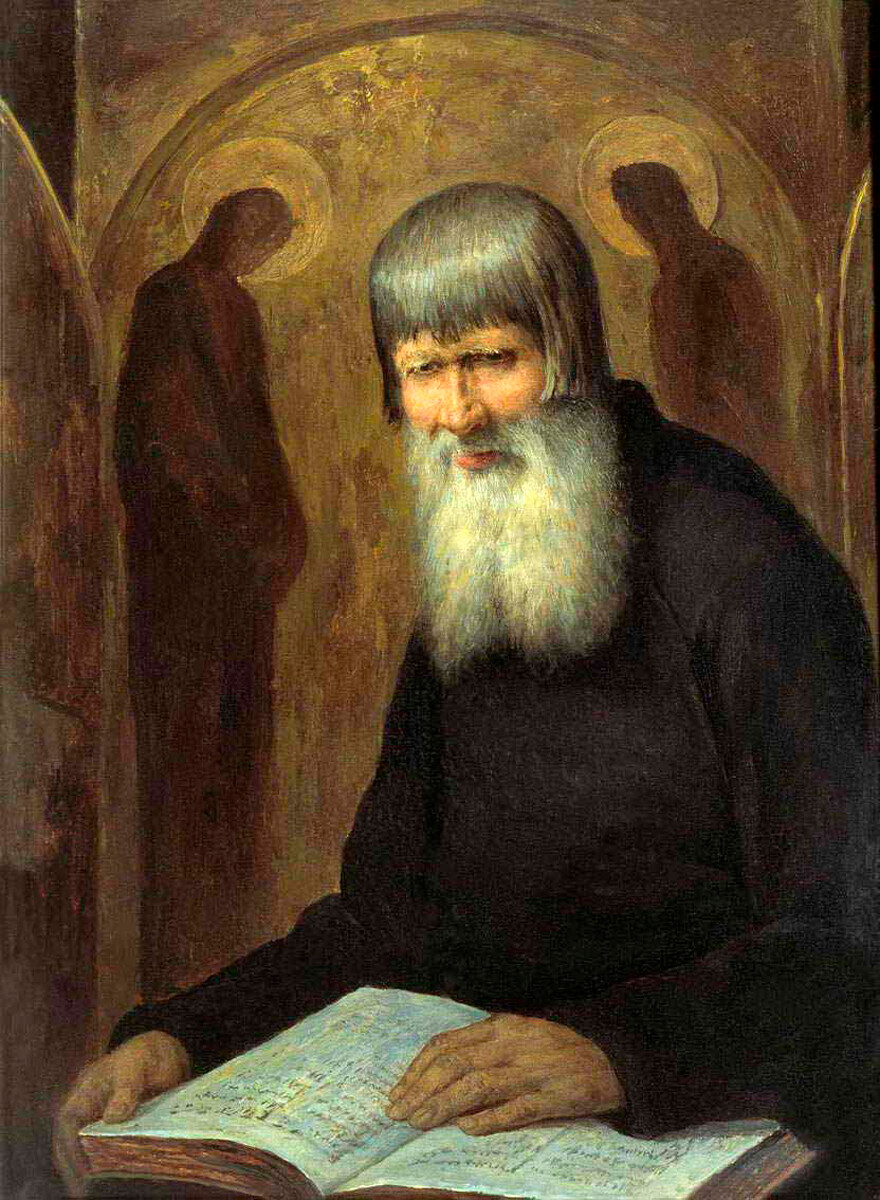

"An Old Believer" by Mikhail Botkin, 1877. The haircut is called "bracket" (в скобу)

"An Old Believer" by Mikhail Botkin, 1877. The haircut is called "bracket" (в скобу)

At the beginning of the 17th century, the hairstyle known as "bracket" (в скобу) appeared, which in imperial times was common mainly among merchants, who in large part were Old Believers. The bangs in this hairstyle were trimmed, and the strands on the sides of the face remained long. The hair could stretch almost to the shoulders. In some communities of Old Believers, the "bracket" hairstyle is still mandatory as a sign of belonging to the body of worshippers.

Wigs, toupees, bags

Prince Alexander Menshikov (1673-1729) wore a grandiose wig and shaved his head, which is clearly visible in this portrait

Prince Alexander Menshikov (1673-1729) wore a grandiose wig and shaved his head, which is clearly visible in this portrait

When Peter the Great reformed all aspects of life and government in Russia, it was clear that both clothing fashion and hairstyles also had to change. Wigs were worn in Europe at that time, but Peter improvised here by wearing semi-long hair because he did not like wigs. Of course, the Russian nobility and most of the military officers had to follow suit. They let their hair grow, covering it with white powder and curls over their temples.

Mikhail Lomonosov wore 'pigeon's wings' hairstyle

Mikhail Lomonosov wore 'pigeon's wings' hairstyle

For example, Mikhail Lomonosov wore his hair in a manner that formed a “pigeon’s wings” hairstyle. Twisted curls were very fashionable for men. To curl hair back in the 18th century, papillotes began to be used – these were pieces of cloth or paper on which the hair was wound to make them curl. Sweet water, beer, and sometimes special grease were used to fix the curls.

The New Cavalier by Pavel Fedotov, 1846. The man in the picture is wearing papillotes in his hair

The New Cavalier by Pavel Fedotov, 1846. The man in the picture is wearing papillotes in his hair

Nevertheless, many men, especially civil servants and courtiers, continued to wear wigs. Historian Vera Bokova says that 18th century officials shaved their heads bald so that it was convenient to wear a "duty" wig. In the morning you got up, washed, put the wig on your bald head and walked around wearing it all day. Wigs needed special care – cleaning, washing, tinting, and braiding. These services were provided by coiffeurs, or toupee craftsmen, as they called the hairdresser back then.

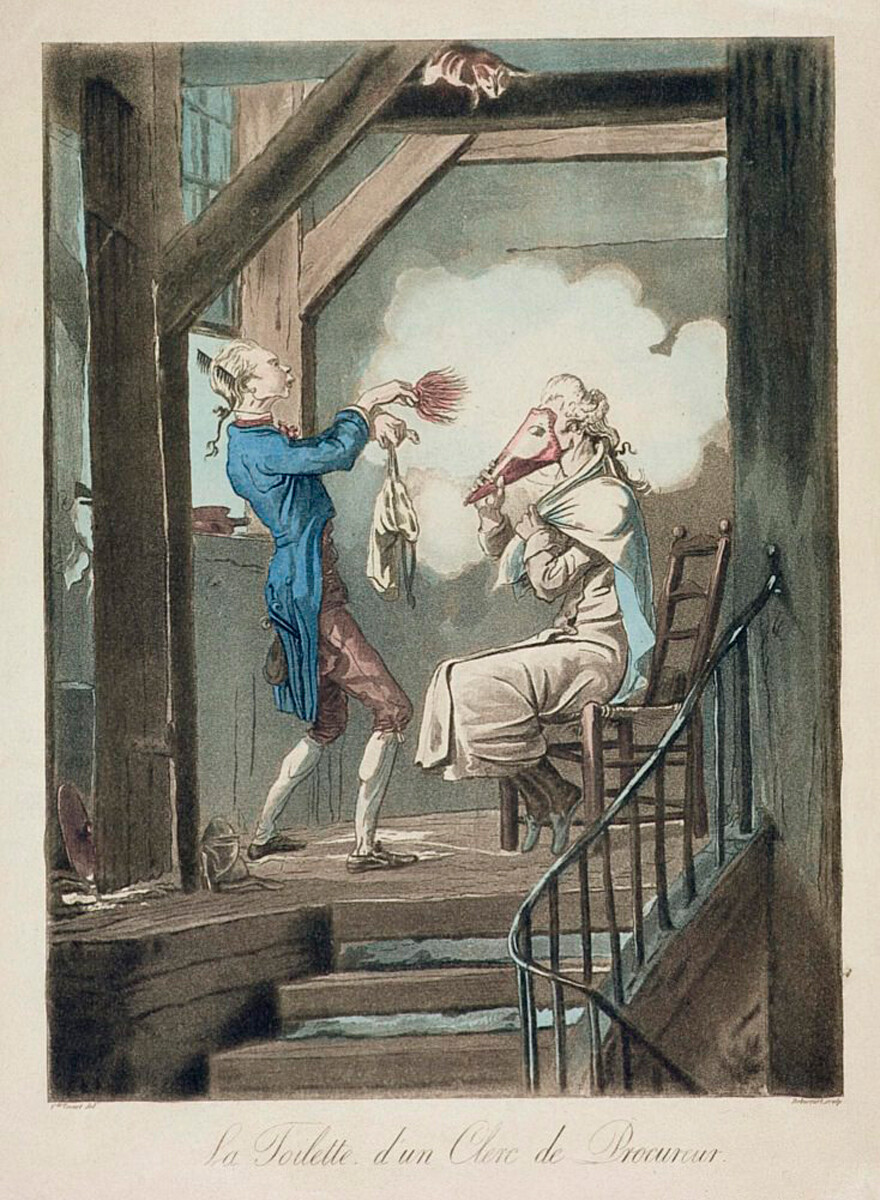

The process of powdering a wig

The process of powdering a wig

The wig had to be powdered often – the gentlemen could go to a coiffeur or teach his servants how to provide the necessary care. Powdering the wig was the final touch of a noble man's toilet, which was done when he was already dressed in a suit. Clothes were covered with a pudermantel (a type of protective cape) from the powder, and the face was covered with a leather or paper cone. The powder was made in a household room – one wig required a kilogram and a half of powder, which a coiffeur or a servant doused on the fortunate fashionista, and the powder flew around.

Portrait of Alexander Lanskoy, 1782 by Dmitry Levitsky. Alexander Lanskoy (1758-1784), one of the favorites of Catherine the Great, is seen here wearing his hair in a high 'toupee' over his forehead

Portrait of Alexander Lanskoy, 1782 by Dmitry Levitsky. Alexander Lanskoy (1758-1784), one of the favorites of Catherine the Great, is seen here wearing his hair in a high 'toupee' over his forehead

In order for a powdered or an oiled wig not to stain the back of one’s outerwear, the bottom was placed in a purse – a fabric bag that was tied on the lower curls or tails of a powdered wig or hairstyle. With the accession of Catherine the Great to the throne, toupees with artificial hair that were combed over the forehead became fashionable. At the same time, the rest of the hair was placed in one or more tails behind the back of the head.

How did the wire get into your hair?

Friedrich II the Great of Prussia, 1745 by Antoine Pesne. This is the haircut with an artificial braid the Russian soldiers had to wear

Friedrich II the Great of Prussia, 1745 by Antoine Pesne. This is the haircut with an artificial braid the Russian soldiers had to wear

In parallel with secular hairstyles, the uniform hairstyles of the Russian military also changed and took on a modern look for the era. But they were also very complicated. During marches, exercises, and actual combat operations, no one cared about haircuts; but there were also reviews, parades, watches, and guards. During all these events, it was necessary to have a hairstyle specially adapted for army service.

Movies about the 18th century have made us believe that soldiers and officers wore white wigs. However, this was not the case – white truly was their hair color, having been moistened with water, kvass, or smeared with wax lipstick made of tallow, after which the head was sprinkled with chalk or flour and made white.

In 1764-1765, Alexander Suvorov personally described the rules of military hairstyles in the "Regimental institution" – "Starting from the crown in the middle, curl a hair braid that’s tied later into a ribbon braid. No toupees are allowed. Temples should be set for everyone in the same manner, as it is now established in the regiment, in one long curl, combed decently so that it does not look like an icicle. In the cold it should be wider so that it covers the ear."

Peter III of Russia, 1761. In this portrait, Peter wears his own hair powdered white

Peter III of Russia, 1761. In this portrait, Peter wears his own hair powdered white

This was how it was supposed to look "in a large regimental formation, in church formations, on guard duty and in any city when walking down the street" – that is, in all cases when the military could be seen and considered. At the same time, the "ribbon braid", that is, an artificial braid, was attached to a wire, firmly grafted to the back of the head. That’s how difficult the full soldier's hairstyle was. To keep it in order, the soldier always (!) had to carry with him: "A comb, a piece of wax lipstick, and a quarter pound powder with a brush in a bag."

In the 1770s, Prince Grigory Potemkin launched the reform of the Russian army and relieved soldiers of having to care for the previously imposed tedious hairstyles. "Curling, powdering, plaiting – is it a soldier's business? They don't have valets. What are these curls for? Everyone should agree that it is more useful to wash and scratch your head than to burden it with powder, lard, flour, hairpins, and braids. The soldier's toilet should be like this: up and go!" wrote Potemkin.

From that time, soldiers began again to have their haircut, as before, "under the pot"; wigs and curls remained only with the guards, who mostly carried out ceremonial duties.

Alas, this respite was short-lived, as the nightmare of wigs and braids returned to the Russian military under Emperor Paul I, who wanted all his soldiers and officers to look just like he did – and he wanted to look like Frederick the Great. The problem is that in 1796 this fashion was hopelessly outdated, and there were few hairdressers among the troops (two per regiment, or less), so the soldiers hardly slept before the shows and parades, powdering and oiling each other's hair. With Pavel's death, this fashion instantaneously became a thing of the past. A new era was dawning – the age of dandyism.

The Great Coiffeur Revolution

Les incroyables, estampe, 1796, C. Vernet. Both of the 'incredibles' (incroyables) are wearing a "dog ears" hairstyle

Les incroyables, estampe, 1796, C. Vernet. Both of the 'incredibles' (incroyables) are wearing a "dog ears" hairstyle

The French Revolution changed the hairstyle fashion across Europe. Everything bulky and lush immediately became "pre-revolutionary." The fashion for light, short and natural hairstyles now made its debut. Some of these styles even mimicked the events of the revolution. For example, one type of hairstyle was named "a la victim": the back of the head was cropped short, almost shaved (so that the neck was exposed), the rest of the hair was cut less short and combed forward. It’s easy to guess that this hairstyle was reminiscent of the victims of French revolutionary repression who died on the gallows.

The revolution gave rise in France to male fashionistas who called themselves "the incredibles". Their clothes were quite exaggerated and ostentatious: they wore huge neckerchiefs, held a gnarled stick instead of a cane, and sported a "dog ears" hairstyle on their head – the hair on the sides of the head remained long, but was combed forward, framing the face with a short haircut at the back of the head.

With the accession of Alexander I, all this flooded into Russia. First of all, many French, fleeing from the butchery and horrors of the revolution, emigrated en masse to imperial Russia. There were many hairdressers among them – in fact, from that time onward they even monopolized the profession in 19th century Russia. The word "coiffeur" was French, and the whole profession of hair-cutting and styling as a whole was "French" – even Russian masters wrote "Coiffeur Sidoroff" or something to that extent on their signs.

Young man, 1809, by François-Xavier Fabre. The young man in this portrait is wearing a haircut 'a-la Titus'

Young man, 1809, by François-Xavier Fabre. The young man in this portrait is wearing a haircut 'a-la Titus'

When Napoleon became emperor of France, the ‘Empire Style’ came into fashion, which had many references to the Roman Empire that Napoleon himself loved. New haircuts were named after Roman heroes and emperors. The haircut "a la Titus" imitated the image of Titus Junius Brutus, the hero of Voltaire's tragedy "Brutus". The face was shaved smoothly, leaving narrow sideburns called "favorites" on the cheeks from the temple, and the hair was cut short and curled. A similar hairstyle is "a la Caracalla", imitating the image of the Roman emperor who ruled in the third century. Both of these hairstyles had sideburns as extensions of their hair, but other sideburns were also worn – lush, like part of a beard. They were called "English".

George Gordon Byron, 1813, Richard Westall. An idol of fashion, Byron wore a hairstyle that became typical for men of the 19th and 20th centuries

George Gordon Byron, 1813, Richard Westall. An idol of fashion, Byron wore a hairstyle that became typical for men of the 19th and 20th centuries

By the 1820s, wigs, curls and hair powder for men started to fall out of fashion. Many men still wore the usual bangs and curls, which were curled either on papillotes or with the help of a hairdresser with hot tongs. All of those fashions were over by the middle of the 19th century, and since then, the styles of men's hairstyles have been similar to the ones we have today.