What traditions, rites & holidays were invented in the USSR in place of Orthodox Christian ones?

“The religious believe that the Virgin Mary is the patron of agriculture. <…> Today, the holiday of Annunciation [to the Blessed Virgin Mary] is observed less often. Kolkhoz workers, who work the land with complex machinery, applying the rules of agricultural technology, know that the harvest depends not on heavenly patrons, but on people and their work in a kolkhoz.” That’s how the ‘1941 antireligionist’s calendar’ edified its readers.

In the USSR, religious holidays that signified the beginning of various agricultural activities were branded as superstitions and “old-fashioned customs” To oppose them, the importance of scientific knowledge and technological progress was proclaimed. This was only one instance of the mass rejection of the Church’s heritage and the systematic reduction of the Church’s influence on the lives of Soviet people.

Workers turn church utensils into scrap metal

Workers turn church utensils into scrap metal

However, the Bolsheviks realized that they wouldn’t be able to simply “cancel” religion: it occupied too important a place in peoples’ lives. The Church was in charge of the calendar, the matters of education; without it, it was impossible to register a marriage or hold a funeral and it also regulated the norms of morality and ethics. So, the communists strove to fill the ritualistic-ceremonial sides of life with a new meaning.

The struggle against religion

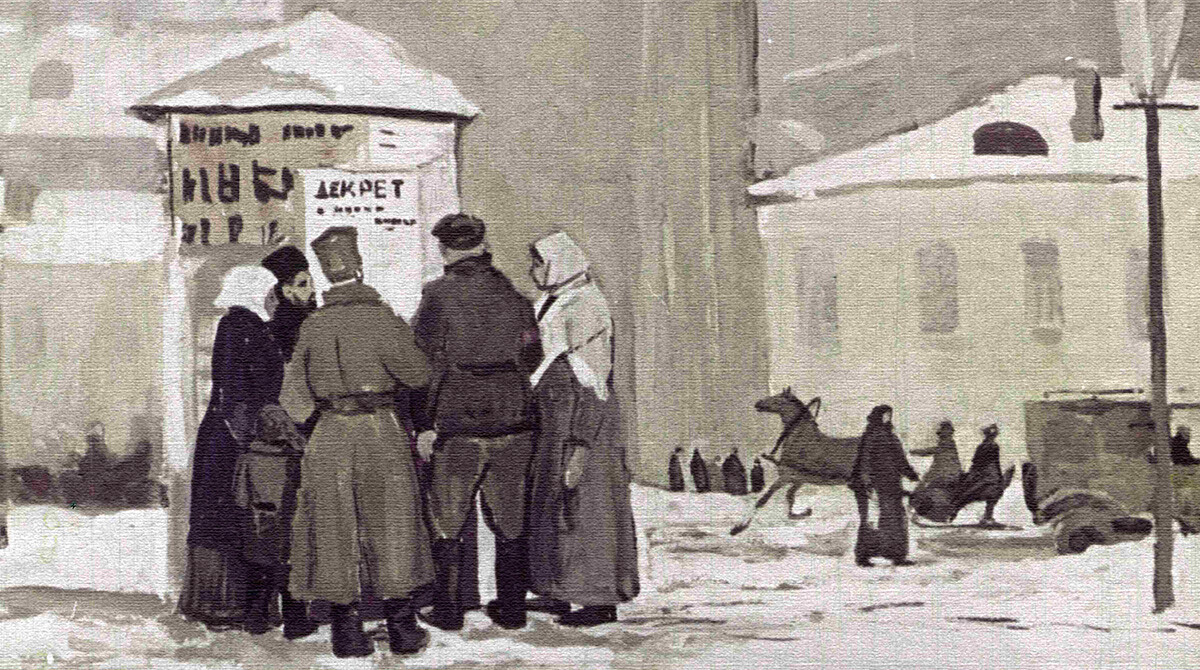

The new authorities began getting rid of the influence of the Church straight after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. The Church was separated from the state, its institutions were defunded, deprived of ownership rights, land and property; the clergy was deprived of their right to vote. Even church marriages lost their legality: for it to count, a civil marriage had to be done.

Most of all, obviously, the Orthodox Church suffered from these persecutions. However, other faiths also got their fair share of trouble – for example, the Old Believers; in time, different sects were also persecuted, whom the new authorities favored for only a very short period of time.

In 1918-1920, the Bolsheviks initiated a campaign of opening the holy relics. In 1921-1922, they began a campaign of seizing church valuables. From 1922, the Anti-Religious Commission was dealing with the matters of faith. Among its goals was the “reformatting” of the religious consciousness of the population and the elimination of Orthodox Christian “remnants”. The League of the Militant Atheists was actively engaged in atheist propaganda.

"Religion is poison. Take care of the children"

"Religion is poison. Take care of the children"

The scenarios of celebrating a Komsomol Christmas and Easter were developing in the country; the publication of various anti-religious literature and periodicals for adults and children was arranged. In these propagandist materials, Church traditions were “exposed” for their “savage” (pagan) roots. Espionage, working for foreign intelligence and enemies of the communists were all attributed to the servants of the cult.

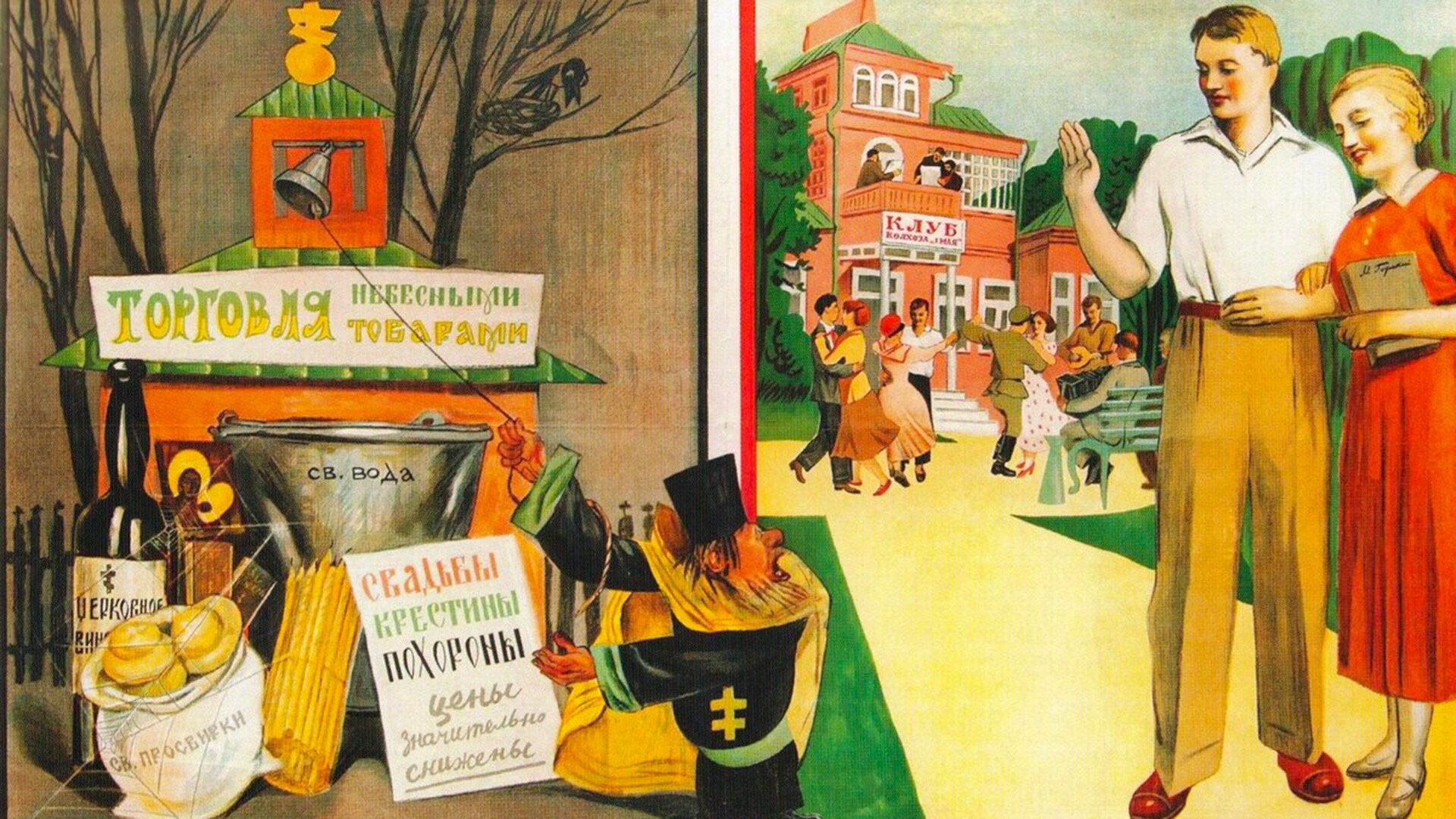

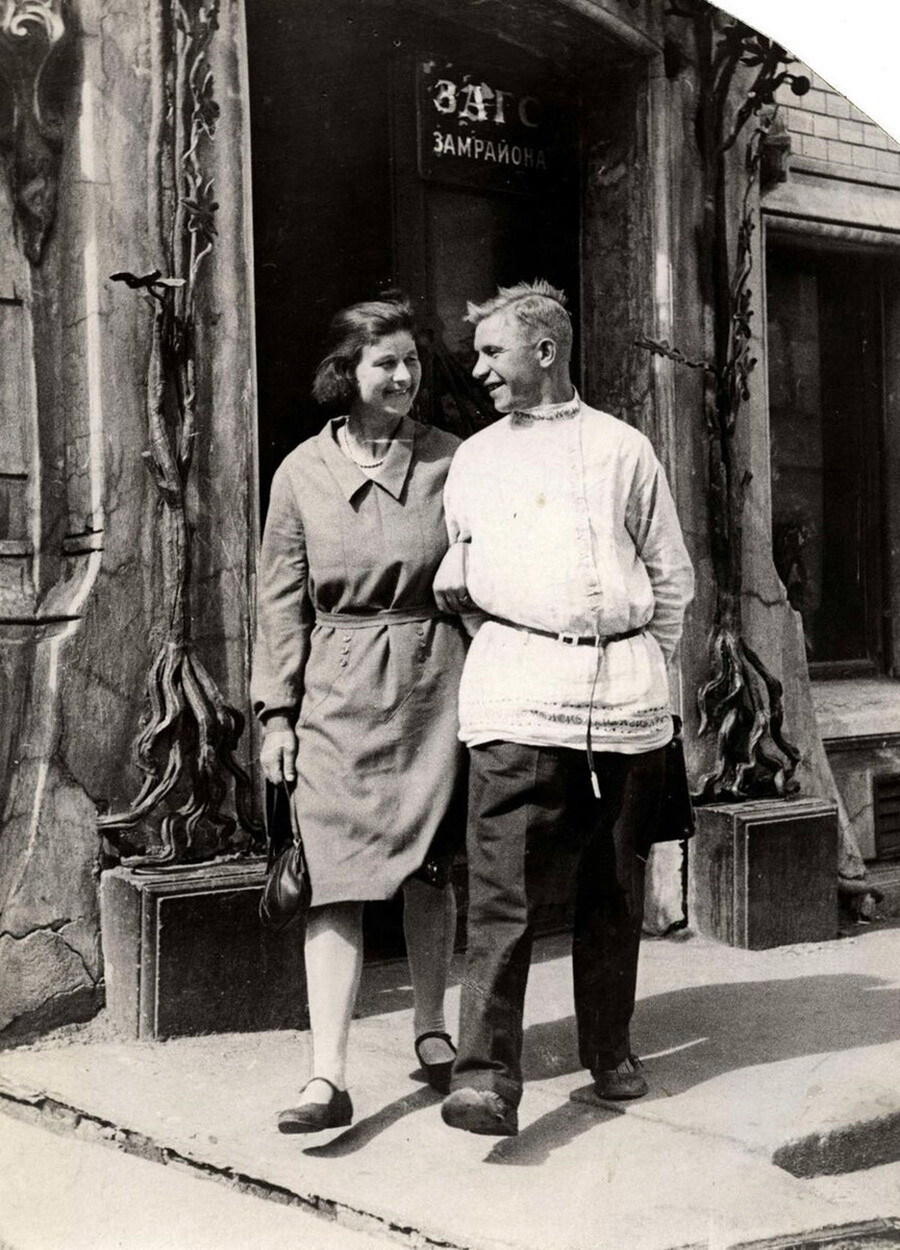

Red weddings

In the 1920s, when Church marriage lost its legality, it was decided to replace the wedding rite with the “red wedding”. It differed from the previous, traditional one in the way that it was not a family event, but a “public” one. And it was the Komsomol – a party youth organization – that mostly dealt with the promotion of the new tradition.

Red weddings

Red weddings

The celebration was held without rings or a white dress, but with the decoration of propaganda posters, instead. The role of the servants of the new cult was performed by the Komsomol and Party organizations’ secretaries, who gave counsel to young couples. As a present, they were given propaganda literature, as well as the works of Lenin and other communist leaders.

A characteristic couplet became a sign of the times: “My mother wanted to wed me in the old-fashioned way – with rings. It turned out differently – in a club with Komsomol members.”

Red weddings

Red weddings

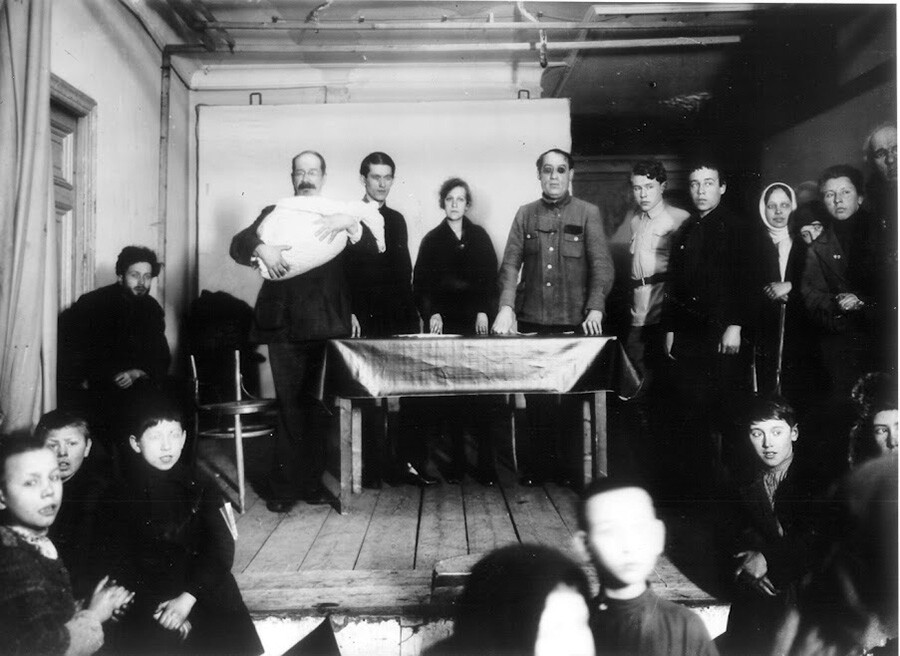

Christening or ‘octobering’

This Soviet version of the Church’s christening was supposed to create a celebration around recording the birth of a newborn in the official civil records. Historian and culturologist Natalia Lebina notes that christenings were most often arranged in factory clubs.

Parents were congratulated by the heads of the Party and Komsomol offices in enterprises. They were presented with Marxist literature and encouraged to call their kids new revolutionary names. For example, Varlen (short for ‘Velikaya armiya Lenina’ – ‘the great army of Lenin’), Vilen and Vladlen (from ‘Vladimir Ilyich Lenin’), Staliya (from ‘Stalin’), Pobisk (short for ‘pokoleniye bortsov and stroiteley kommunisma’ – ‘the generation of fighters and communism builders’).

People's Commissar of Education A. Lunacharsky takes a child at "oktyabrins" in a Moscow workers' club. November 16, 1924

People's Commissar of Education A. Lunacharsky takes a child at "oktyabrins" in a Moscow workers' club. November 16, 1924

Red funerals

Funerals were as important a ritual event as christenings and weddings and they also had to be reformatted. First of all, funerals were to be held without a priest and memorial services. A traditional funeral service of the deceased was allowed only after receiving death registration certificates in the local bodies of the Soviet authorities.

Funerals of victims of the February Revolution. Members of the funeral committee

Funerals of victims of the February Revolution. Members of the funeral committee

The propaganda of cremation also harmed the traditions. In Orthodox Christianity, it is prescribed to bring the bodies to the earth and not to the fire, so the Bolsheviks viewed corpse burning as a part of their anti-religious campaign and called the new system ‘chair of atheism’. At the beginning of 1919, Lenin signed a decree on permitting and even preferring the cremation of the deceased.

The first crematorium in the country appeared in December 1920 in Petrograd (St. Petersburg). It operated for two months. With the transition from the emergency measures of war-time communism during the Civil War to the New Economic Policy, the authorities stepped away from burning corpses after all. However, a second crematorium was eventually built in Moscow in 1927. “A crematorium spells the end of incorruptible relics and other miracles. A crematorium means hygiene and the simplification of burials, it means reclaiming land from the dead for the living,” the ‘Ogonyok’ magazine wrote in the same year.

New calendar milestones

Until the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, public holidays were mostly linked to religious holidays – Christmas, Easter, the Ascension of Jesus, as well as others. Historian Andrey Tutorsky writes that the majority of contracts both in villages and in factories were signed from the Intercession of the Theotokos to Easter; to cancel it would mean to break the entire system of annual planning of most of the population of Russia. So, the tradition was not broken abruptly, but some measures were taken.

At the beginning of 1918, the Council of People's Commissars accepted the Decree on the transition to the Gregorian calendar. This was done for two reasons. Firstly, not to “lag behind” the majority of the countries of the world. Secondly, to break the Church’s tradition. Before the revolution, Russia used the Julian calendar, since it was used by the Orthodox Church, which resisted transitioning to the Gregorian calendar. In Soviet Russia, for example, Christmas “migrated” from December 25 to January 7; until 1927, it was a day off.

At the same time, new dates were established close to the old holidays and people were literally forced to celebrate them in working collectives. This way, the civil tradition of celebrating New Years on January 1 stuck – with the Christmas tree, initially an attribute of Christmas. May 1 was welcomed with demonstrations in honor of the ‘Day of the International’ (later – the ‘Workers’ Solidarity Day’), November 7 – with demonstrations in honor of the anniversary of the October Revolution.

"Religion is the brake of the five-year plan!"

"Religion is the brake of the five-year plan!"

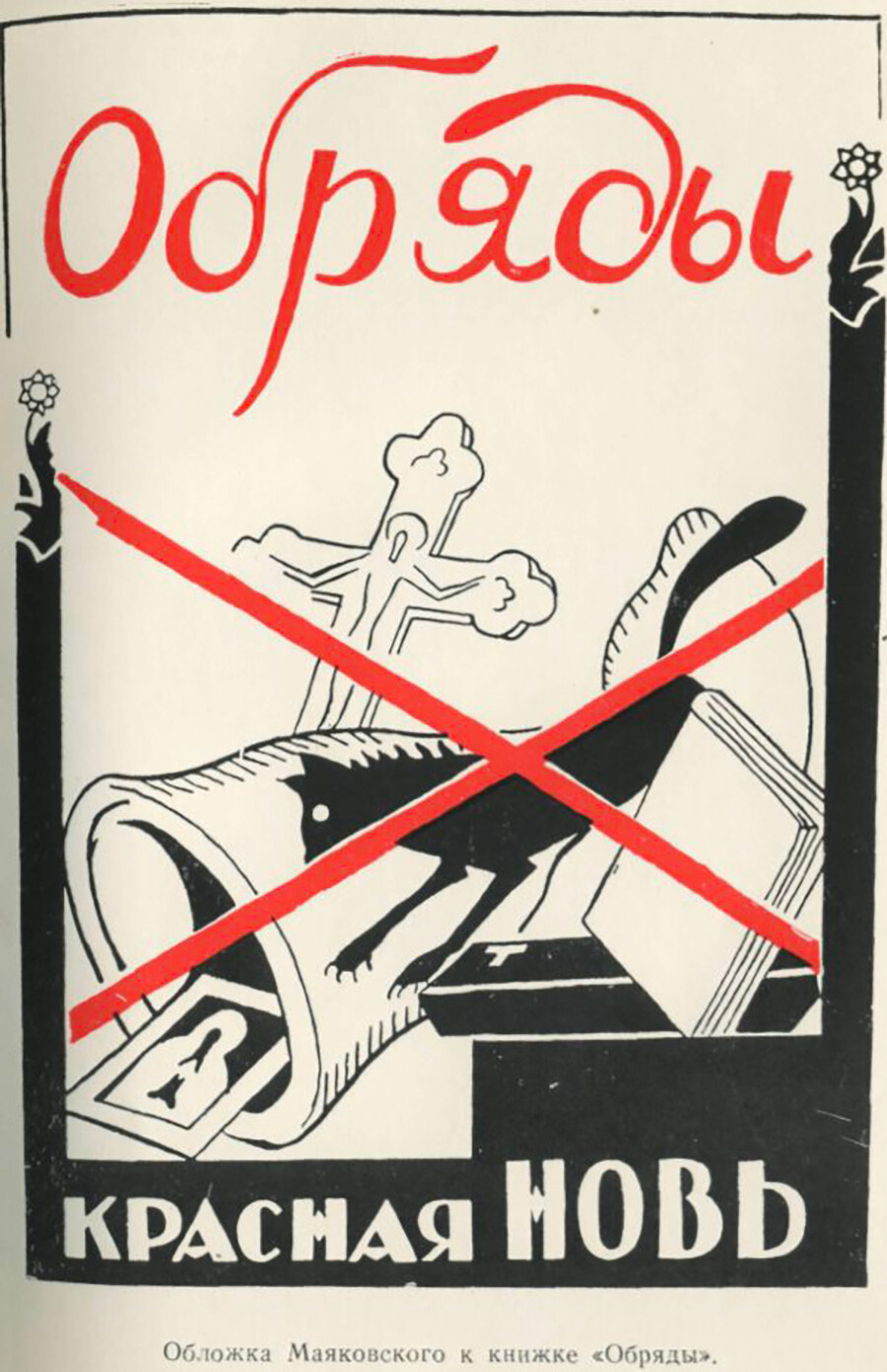

“Hand the resignation letter to Christ. Our mentor is knowledge, a book is our teacher. Cast away the sowing of superstition. Cast away the rite of religions. The resurrection of the Commune is October 25 [the date of the October Revolution by the Julian calendar – author’s note]. Our place is not in a dirty church. To the streets! Poster in hand! On our holidays, blaze science like fire over faith,” Vladimir Mayakovsky wrote in 1923.

V. Mayakovsky, "Rites", book cover.

V. Mayakovsky, "Rites", book cover.

Despite the propaganda, red weddings, red funerals and christenings were not really catching on in the country. First – because of poverty and harsh life conditions, characteristic of the first post-revolutionary years: people had no time for celebrations, even ascetic ones. Aside from that, if, in cities, the new rituals drew the attention of the working youth, in villages, the traditional worldview was unshakable. Later, during the years of the New Economic Policy (1921-1924) the liberalization of the regime came and the control and supervision over the celebrations on “proper” days were loosened. Finally, in 1943, Soviet authorities set a course for restoring their relationship with the Church, which also improved the position of the religious somewhat.

But, the calendar stayed as a firm Soviet heritage. Moreover, Orthodox Christians still celebrate Christmas on the ‘Gregorian date’ – January 7.