Maslenitsa – how a Slavic pagan celebration became a popular Russian holiday

And the fact that, during this week, people also participate in wakes, in sacrificial rites and in pagan fertility rituals doesn’t bother anyone. All these traditions are relics of pre-Christian Slavic customs. For them, Maslenitsa symbolized the awakening of nature, its renewal and fertility, which also meant preparation for the upcoming field work.

What ideas were key for Slavs who were celebrating Maslenitsa?

The Sun

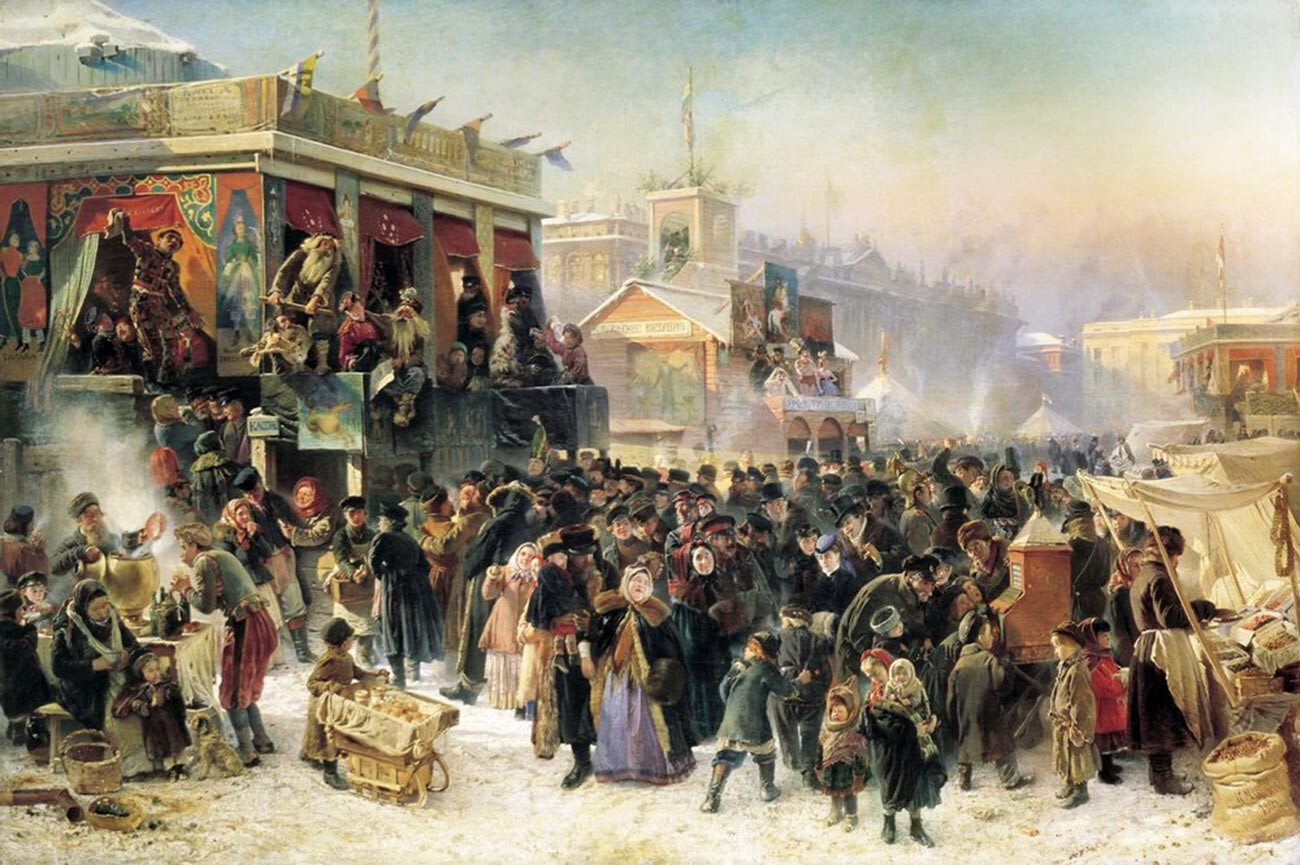

Maslenitsa celebration on Admiralteyskaya Square in St. Petersburg.

Maslenitsa celebration on Admiralteyskaya Square in St. Petersburg.

The coming of spring meant that the sun would begin shining brighter and longer. Our ancestors imagined the sun as a fiery wheel that rolls across the sky, the day changing the night. That’s how a wheel became an attribute of sun rites.

Burning the Maslenitsa Scarecrow.

Burning the Maslenitsa Scarecrow.

“Russian villagers, greeting the spring sun during Maslenitsa, pull around a sleigh with a pillar erected in the middle and a turning wheel is installed onto it. In Siberia, a young man in a woman’s dress and a kokoshnik is put onto the wheel, which is in line with our folk legends, representing the sun in a feminine image,” folklorist and Slavic peoples’ culture researcher Alexander Afanasiev wrote in his book ‘Slavic poetic views of nature’ (1865-1869).

The rain

Maslenitsa.

Maslenitsa.

Along with the sun, life-giving water was no less important to the peasants – spring rains and thunderstorms that special rituals were supposed to “summon”. In the consciousness of the ancient people, the sky was seen as an ocean, with clouds as boats or ships sailing it.

“Not too long ago in Arkhangelsk for Maslenitsa, a bull was rolled around the city on a giant sleigh pulled by twenty or more horses: this was the spring appearance of Perun (the Slavic god of thunder and lightning), rushing around in a thundercloud. According to different poetic views, the thunder god himself appeared in the shape of a raging bull; or he, as a shepherd, herded cloud cows into the sky and milked them with lightning,” the academic writes.

The battle between good and evil

The change of seasons was seen as the struggle between the passing winter (and otherworldly forces connected to it) and the coming spring (and the flourishing of life).

The change of times, the battle between two origins was reflected in ritualistic duels, which had a competitive nature. These included Russian fistfights “crowd vs. crowd”, the Maslenitsa ball game and the capturing of the snow fortress, as noted by Russian folklorist-Slavist and ethnolinguist Tatiana Agapkina in the book ‘Mythopoetic foundations of the Slavic folk calendar. Spring-Summer cycle’ (2002).

Sacrifice

Maslenitsa in Suzdal/

Maslenitsa in Suzdal/

The change from winter to spring was accompanied by the ritualistic “killing” of a hay effigy, burned on the fourth day of the Maslenitsa week. Folklorist, ethnographer, linguist and archaeologist Vsevolod Miller (1848-1913) believed that the effigy represented the old year that was slain before a new one could arrive. Evgeny Anichkov (1866-1937), another folklorist, supposed that the effigy symbolized death and its burning – the triumph of life.

Soviet linguist Vladimir Propp (1895-1970), in turn, noted: the effigy was not just burned. The ashes were afterwards buried into the ground to reinforce its productive forces and promote fertility. It was important that peasants performed the ritual on a sown field.

A similar ritual was conducted at homes: small puppets were burned; the ashes were then thrown out in the yard to the cattle to promote their fertility, as Soviet ethnographer A. B. Zernova writes. The effigy, ‘Maslenitsa’, needed to be burned before the Great Lent. That only highlights the pagan nature of this celebration.

Facilitating life

The key meaning of the Maslenitsa week was to create the conditions to facilitate life.

In particular, khorovod was supposed to fulfill this purpose: a dance of moving in a circle that represented the process of twining and twirling as a metaphor for the emergence of life, aimed to obtain a good harvest of grains, Tatiana Agapkina notes. A similar task was assigned to sledding and the Maslenitsa sleigh riding: the longer the ride, the longer flax would grow.

The idea of fertility didn’t just mean the fields and the cattle, but also the people. Young people were supposed to engage in premarital games – especially sleigh riding together; public kisses were also allowed. Single men and women were not just encouraged to marry soon, they were ridiculed by tying a small piece of a log to their legs (or put on their necks) as “punishment”, which symbolized stocks.

Read more: 5 strange Maslenitsa traditions

During the festivities, swearing, shouting and couplets with erotic contents were widespread at the Maslenitsa fire.

Remembrance

According to the beliefs of peasantry, dead ancestors were present both in the other world and in the ground – which meant they could influence its fertility. So, it was important to appease them – to remember them. Blini were the main dish of the remembrance feast in Rus’.

In some places, the first blin pancake was left on a windowsill – for the ancestors; in other places, it was taken to a grave or eaten for the peace of a soul. As such, it was intended for the deceased, it was a tribute of sorts to the ancestors, providing a connection to the afterlife.

Naturally, blini became a part of Maslenitsa festivities.

In 2022, VCIOM conducted a survey and learned that, during the Maslenitsa week, 87% of Russians planned to eat blini.