What travel was like in 19th-century Russia

Where they traveled

For a long time, a vacation meant a trip to one's family estate - for example, for the summer - or going on a hunting trip or a pilgrimage. Travel in the modern sense came into fashion thanks to Peter I. Having visited European water spas, he decided to organize similar resorts in Russia. This was how the Martsialnye Vody mineral water spa in Karelia came into being, followed by spas at Yessentuki, Pyatigorsk and Kislovodsk in the Caucasus. By the mid-19th century, whole spa towns had sprung up there, with alleys for promenading, bathing establishments and pump rooms. The only problem was how to get there.

Getting ready for a journey

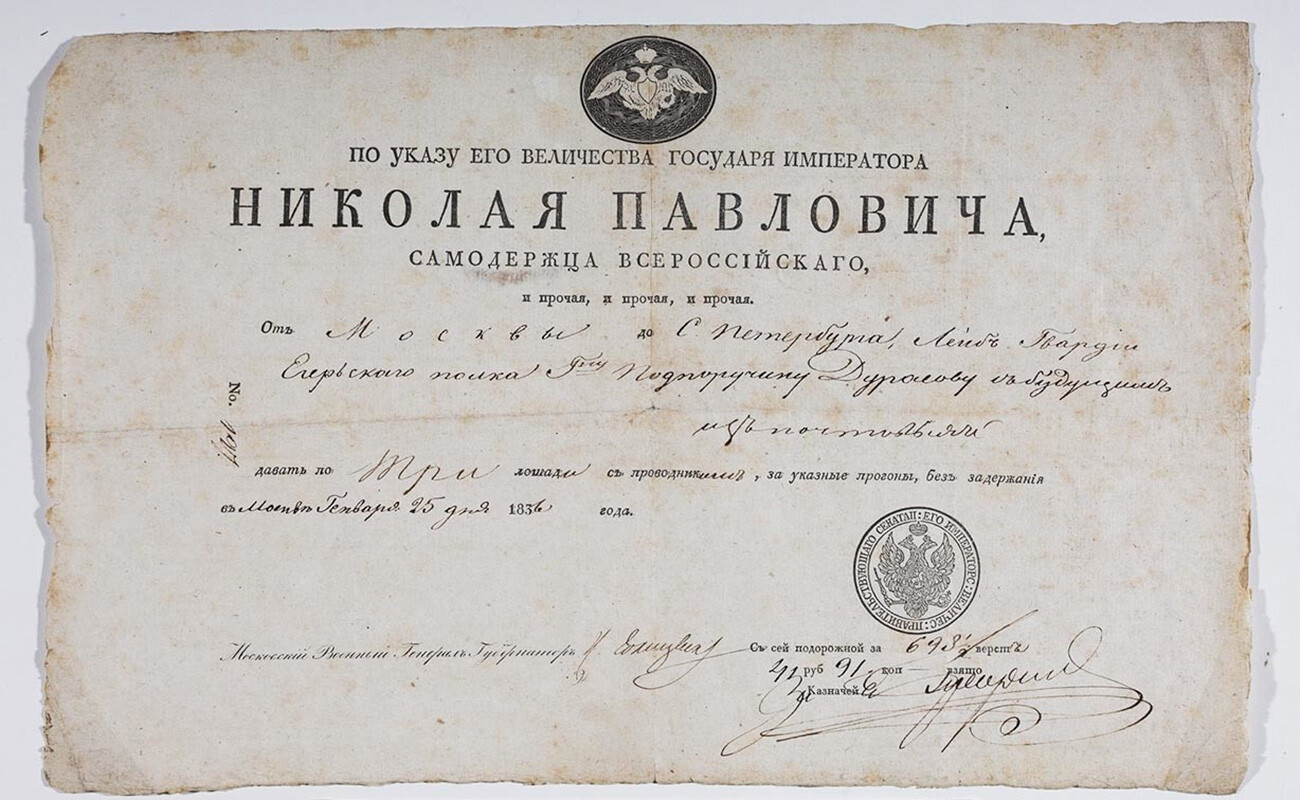

The process of getting ready for a journey was akin to “pereezd srodni pozharu” ("having your house catch fire three times"), as a Russian saying goes. It was necessary to obtain a travel document from the governor or head of the local police department, in order to leave your hometown without problems. The document, which stated the destination of travel, served as a passport and partly as a visa. All this information was recorded at checkpoints and details of traveling nobles, if visiting a major city, were even published in newspapers.

The cost of the entire trip depended on whether one had a travel document: Without this piece of paper, travelers had to renegotiate the price they paid for a coachman's services or to hire horses.

Cavalrywoman Nadezhda Durova once foolishly heeded someone's advice not to obtain a travel document and, as a result, her trip from Kazan to St. Petersburg cost 600 rubles; had she obtained the "travel card", it would have been half the price. Alexander Radishchev, author of ‘Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow’, described the travel document as a "letter of protection" and "carried it as people sometimes carry a cross to keep them out of harm's way".

What modes of transport were used

People traveled by coach. Depending on how well off they were, they went either in their own coach or in a stagecoach. In summer - by cart, carriage or ‘tarantass’ (a large, springless four-wheeled carriage) and, in winter, by sleigh, ‘kibitka’ (covered sledge) or ‘britzka’ (carriage with a folding top). Budget permitting, they could travel in a sleeper carriage equipped with every essential - from medicine box to travel bed. Travelers also often used their own horses and this method of getting from one place to another was most economical. It was called taking a "slow journey": Travelers proceeded at their own pace with lengthy stopovers for rest along the way. Both a carriage and the horses could also be hired: At post stations, the horses were changed and the luggage transferred to a new carriage, giving rise to the expression "to travel by post-chaise".

Everything depended on whether any horses would be available at the next station or whether it would be necessary to wait. The stables at one of these stations usually held up to 25 horses. And this was where bureaucratic red tape kicked in: The higher the rank of the traveler, the greater the horsepower he was entitled to. Admiral-generals and chancellors were given up to 20, senators 15, privy counselors 12, captains and titular counselors three and everyone else - two. If someone important had passed through a post station the day before, travelers arriving afterwards would in all probability need to stay the night to await new horses.

Speed of travel also wasn't very fast: something like 10 ‘versts’ (around 10.6 km) per hour in summer and up to 12 ‘versts’ (12.8 km) per hour in winter. It was possible to cover 100 ‘versts’ (a little more than 100 km) in a single day, but that was officially. A stagecoach driver could technically go faster for a separate payment - and then the passengers could do up to 200 versts a day. Furthermore, passengers had to pay a so-called ‘distance charge’ for travel between two post houses. For example, the journey from Mikhaylovskoye to St. Petersburg cost 120 rubles for just over 400 km and when Pushkin was being sent into exile to a "distant northern district" from Odessa to Pskov, he was issued with 389 rubles for the distance charge - ahead of him lay a journey of 1,621 versts (around 1,729 km). By way of comparison, a low-ranking official of the time received an annual salary of up to 700 rubles, so journeys not on official business were by no means cheap.

Founded in 1820, the first private transport company, the ‘Society for the Initial Establishment of Stagecoaches’, offered a ride-sharing service. Passengers could travel four to a coach without a large amount of baggage. Tickets still weren't cheap - from 55 to 95 rubles. They were typically purchased two weeks before travel and passengers had to present a passport and an authorization from the police certifying there were no restrictions to their travel. And, with the opening in 1834 of the first major road between St. Petersburg and Moscow, journey times became even quicker: If passengers had previously bobbled along in a coach for up to six days, now the coaches "flew with the wind" between the two cities in just four days!

What did they take with them?

Cost-conscious travelers who took a "slow journey", in other words traveled in their own carriage and with their own horses, took absolutely everything with them: clothes, food, firewood and books, as well as special hot-water urns - in other words, any item, even the smallest trifle, that could come in useful during the journey.

Travelers using post horses would stop at a post house or at a victualing house (a wayside eatery) where they could take some refreshment and have a rest. Here additional services were also to be had: A lame horse could be shod (fitted with new horseshoes) or repairs to a carriage undertaken.

Where did they stay?

The first European-style hotels started springing up in the 19th century. Apart from boarding houses and hotels at mineral springs and seaside resorts, it was also possible to stay in furnished rooms and hotels in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

On the road, the price depended on the quality of the post house: It might be an establishment with no more than a relaxation lounge, in which travelers could doze while seated, or it could be a coaching inn with rooms no different from hotel accommodation and with a billiard room and perfectly adequate food.

The cost of a room in a "decent" hotel ranged from two to 50 rubles - for instance, the three-story Chelyshy hotel owned by merchant Pyotr Chelyshev, complete with bath house, tavern and rooms, or the Evropeyskaya hotel in St. Petersburg.